Microsoft has initiated one of its biggest management shakeups in years, as it announced today that Robbie Bach and J Allard, the masterminds behind the company’s hugely successful push into video-game consoles, are leaving the company after decades of leading the Windows giant into new markets.

Microsoft has initiated one of its biggest management shakeups in years, as it announced today that Robbie Bach and J Allard, the masterminds behind the company’s hugely successful push into video-game consoles, are leaving the company after decades of leading the Windows giant into new markets.

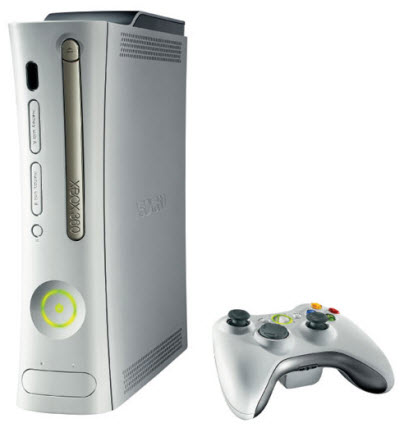

Bach (pictured left), the head of Microsoft’s Entertainment & Devices group, is retiring after 22 years at Microsoft, according to an announcement today by Microsoft chief executive Steve Ballmer, who said that Bach is “leaving on a high note.”

The two men are not being directly replaced. Don Mattrick, head of the game business under Bach, will now report directly to Ballmer, as will Andy Lees, head of the mobile communications business that includes the upcoming Windows Phone 7 operating system. David Treadwell will join the interactive entertainment business group to lead the technology development that Allard (above, right) supervised. Both Bach and Allard have now commented on their reasons for leaving in interviews with TechFlash. Both say they separately decided it was time for them to move on.

Bach was responsible for managing the Xbox and PC game business, and he supervised Allard as the group tried to take on Apple head-on with the Zune music player, Windows Mobile, and now Windows Phone 7.

Bach was responsible for managing the Xbox and PC game business, and he supervised Allard as the group tried to take on Apple head-on with the Zune music player, Windows Mobile, and now Windows Phone 7.

Were they innovators or copycats? A little of both. But they were products of Microsoft’s relentless culture of trial-and-error design, as I wrote in my books, Opening the Xbox and The Xbox 360 Uncloaked, which are the sources for much of the information in this story. Microsoft had a habit of being a fast follower. If someone emerged with something innovative, such as the iPod, Microsoft chased it and iterated on its efforts. The early products were often obvious clones, filled with bugs. But the latter products were often so good they beat rival products.

“Not everything I’ve worked on started out easy, and, in fact, a lot of the things I worked on started out really hard,” Bach said in his interview with TechFlash today. “But the ability to be persistent about that, to keep attacking, keep working at it is important.”

The most complimentary thing said about both Allard and Bach was that they built great teams that got the job done. For instance, Allard’s team of a handful of engineers was able to create the bare bones game operating system for the Xbox. Normally, Microsoft assigned gigantic teams to handle such tasks. Allard’s technical wizards were known as “friends of J,” or the FOJ. He referred to them in his parting memo today as The Tribe.

Their projects included some of Microsoft’s greatest business triumphs as well as its worst failures. Bach rose through the ranks in Microsoft’s Office division. His leadership helped Microsoft go from last place to first in productivity suites, which became the cash cow alongside Microsoft’s Windows business. Bach was known inside Microsoft as a “shipper,” or someone who had gotten products out on time. With the Xbox video-game console, Bach had to make the major business decisions that floated up to him from the product designers, which at various points in time included Ted Hase, Otto Berkes, Seamus Blackley, Kevin Bachus, Cam Ferroni, Ed Fries and Allard.

Of that group, James “J” Allard (he always went by J) had a reputation as a shipper as well. He joined Microsoft in 1991 as a networking programmer and his goal was to marry the internet and Windows. He ran an unsanctioned project in early 1993 to create Microsoft’s first internet server. On Jan. 25, 1994, he penned a memo, “Windows: the Next Killer Application for the Internet.” He inspired Bill Gates to reorganize the entire company around internet technologies.

Of that group, James “J” Allard (he always went by J) had a reputation as a shipper as well. He joined Microsoft in 1991 as a networking programmer and his goal was to marry the internet and Windows. He ran an unsanctioned project in early 1993 to create Microsoft’s first internet server. On Jan. 25, 1994, he penned a memo, “Windows: the Next Killer Application for the Internet.” He inspired Bill Gates to reorganize the entire company around internet technologies.

Allard (right) was recognized as a rising star and nicknamed one of the “Baby Bills” after Bill Gates. But on his next major effort, Project 42, he didn’t get along with his boss and his work was eventually tabled. It later became the underpinnings of Microsoft’s .Net technology. Allard took off on a sabbatical and played a lot of video games. He heard from Microsoft engineer Nat Brown that Microsoft was cooking up a game console.

Microsoft’s team had been alarmed about Sony’s bluster about the PlayStation 2, which was supposedly going to hit the earth like a comet and wipe out the dinosaur PC. To counter that, Hase, Berkes, Blackley and Bachus began agitating from below to start a big effort in game consoles. Hase and Berkes wanted it to be a PC, but Bachus and Blackley were open to the idea of making a game console. At the same time, seeing the threat from Sony, Bill Gates started asking what the company could do in games. The fear was that the PS 2 was a Trojan Horse, getting into homes as a game console and then becoming an entire home entertainment system that supplanted the computer.

At first, Allard didn’t join the Xbox team because he thought an “eMachines for games” device, with a custom version of Windows and a sub-$500 cost, just wouldn’t be competitive with game consoles. Ballmer, in recruiting Allard to join the Xbox team, said, “Go make this real.” Later, Allard said, “It was a chance to do something with a more profound impact on society.” So he accepted. He brought bravado to the leadership of the team, saying, “What gets me out of bed and into the office every day is the thought of Ken Kutaragi’s resignation letter, framed, hanging next to my desk,” referring to Sony’s longtime PlayStation chief. That was just so much bluster, but years later, Kutaragi did indeed resign after the PS 3 disappointed everyone.

A lot of arguments ensued about how to do Xbox right. On the original Xbox project, Allard argued technical points upward; for instance, he and a few others convinced Bill Gates that the Xbox shouldn’t run Windows. That turned out to be one of the best technical decisions they made, since Windows was a resource pig that would have slowed games down. He also argued that Microsoft should include broadband-only Ethernet connections in the box, avoiding the slow phone modems that were more popular at the time. That decision had mixed results, but the Xbox Live online game service that Allard pioneered turned out to be a great hit as games such as Halo 2 became even stronger thanks to the online multiplayer play. Indeed, Xbox Live is Allard’s enduring legacy in the Xbox business. The service is now profitable and it is far ahead of Sony’s online service, the PlayStation Network.

Bach (pictured right), Allard and Blackley were the public face on the Xbox. All of them worked to get game developers on board so that Microsoft would be viewed as a credible counterforce to Sony and Nintendo in game consoles. Bach didn’t play games, but his involvement meant that Microsoft would approach the project as a business that would eventually be profitable. Allard had the technical chops to make sure that Microsoft designed the project right. And Blackley, a former game developer, (as well as his colleague Bachus) had the right connections with the game developers to convince them to invest in something new.

Bach (pictured right), Allard and Blackley were the public face on the Xbox. All of them worked to get game developers on board so that Microsoft would be viewed as a credible counterforce to Sony and Nintendo in game consoles. Bach didn’t play games, but his involvement meant that Microsoft would approach the project as a business that would eventually be profitable. Allard had the technical chops to make sure that Microsoft designed the project right. And Blackley, a former game developer, (as well as his colleague Bachus) had the right connections with the game developers to convince them to invest in something new.

They launched Xbox in 2001, gaining considerable market share and taking second place in game consoles away from Nintendo. That was a great result for their first attempt, but the venture cost them billions of dollars in losses. (I lost count at $6 billion). Microsoft was one of the few companies in the world that could afford to make such an investment to barge into an established market. Allard was recently called the “father of the Xbox,” but that’s baloney. He wasn’t the first on the project; and Xbox itself had many different fathers who made critical contributions. Allard got more credit than he deserved, but, like Blackley, he had an out-sized personality. He was an enthusiastic Xbox Live gamer; his gamertag identification was HiroProtagonist, named after the main character of Snow Crash, Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi novel about living inside a fully populated virtual world.

Blackley left the company and Allard took on a much greater role as head of the Xbox 360’s design. He tried to inspire the team by getting them to imagine what they wanted a cover story in Time magazine to say about the launch of the Xbox 360. (Few people saw the document in which he conveyed that message, but Time magazine did put Bill Gates and the Xbox 360 on its cover.)

Bach, Peter Moore (former chief at Sega’s U.S. operation, now at Electronic Arts), and Allard also had to decide when to launch against Sony, which had allied itself with IBM and Toshiba to make the Cell microprocessor for the PlayStation 3. Microsoft had entered the market with the Xbox about 20 months after the launch of the PlayStation 2. By the time the first Xbox sold, Sony had already sold 25 million units. It was pretty much game over before Microsoft got in the race.

With the Xbox 360, Bach insisted to the product teams that they launch at the same time as Sony and Nintendo. As best they could figure, that was 2005. In 2003, after a retreat at the Salish Lodge at Snoqualmie Falls (the site of the waterfall in the opening of the Twin Peaks TV show), Bach penned a short memo that laid out Microsoft’s strategy. He wanted the console to ship on time, he wanted the division to be profitable in 2007, and he wanted it to be a game box, first and foremost. It could add other digital entertainment, but the Xbox 360 had to nail the gaming experience. The memo gave marching orders for Allard, and it turned out to be a manifesto for success.

As Allard moved forward with a bake-off for the industrial design of the machine, Microsoft’s machinery went into action. Hardware designers from Microsoft’s WebTV acquisition got involved under the command of Todd Holmdahl. Holmdahl’s team churned out chip designs with IBM and ATI. They wanted to make sure that the console would be great for high-definition TVs, which were just beginning to ship in large volumes.

Meanwhile, Allard had to work on tough problems like backward compatibility for games on the original Xbox. Allard designed the console as a web-connected device that could be constantly updated with new features. Microsoft has used that feature as an advantage, being the first to launch movie downloads, Netflix instant watch videos, as well as Facebook and Twitter integration.

Bach’s decision to launch in 2005 was controversial. By luck, Sony and Nintendo both delayed their machines until 2006. Sony in particular had trouble integrating a costly Blu-ray movie player into the PlayStation 3, while Microsoft chose to use DVDs. Meanwhile Nintendo created the game-changing Wii, which ultimately took the biggest market share. By beating its rivals to market, Microsoft grew its market share. It has sold more than 40 million Xbox 360s, compared to just 25 million original Xbox consoles. And the company has sold so many games that the Xbox business is intermittently profitable. Inside Microsoft, that was a great victory, even though Nintendo has sold more than twice as many Wiis.

But Bach’s rush to market also led to a disaster. The product quality of the Xbox 360 wasn’t up to par. Warnings went up and down the chain, but Microsoft executives did not pay enough attention to the perils of launching too early. Microsoft had a culture where you shipped your software and fixed bugs later. But with hardware, that strategy was a recipe for consumer outrage.

But Bach’s rush to market also led to a disaster. The product quality of the Xbox 360 wasn’t up to par. Warnings went up and down the chain, but Microsoft executives did not pay enough attention to the perils of launching too early. Microsoft had a culture where you shipped your software and fixed bugs later. But with hardware, that strategy was a recipe for consumer outrage.

Millions of machines were defective, suffering from the Red Rings of Death that we chronicled in a series of posts on VentureBeat. Microsoft had to take a $1.05 billion to $1.15 billion write-off to pay for the cost of returns. The damage to Microsoft’s reputation was pretty severe, as one survey noted that 24 percent of the consoles failed after two years. The normal defect rates for consumer electronics products are about 2 percent.

Allard, meanwhile, turned his attention to Microsoft’s other enemy, Apple, whose iPod was leading it to a resurgence. Allard led the team that designed the Zune music player, as well as its sequel the Zune HD. Both were abject failures, since Apple’s iPod hardware and iTunes media store proved to be unbeatable. In this regard, Allard’s attempts to take on Apple were regarded as copycat maneuvers, too little to late. The same fate befell Windows Mobile, the phone operating system whose market share has tanked with the rise of the Apple iPhone. Bach’s latest effort to take on Apple is the Windows Phone 7 operating system, which tightly integrates PC functions with a phone. But Apple’s iPhone already has a huge advantage in that market.

Allard’s last project at Microsoft was Courier, which Ballmer canceled earlier this year. It was viewed as an attempt to take on the Apple iPad. Allard said today he did not quit because of Courier, but he wanted to do more personal adventures such as bike and off-road truck racing.

While Bach’s division is profitable now, it may be remembered for its inability to take on Apple in the increasingly critical mobile business. And that may explain why, any day now, Apple’s market capitalization is going to become bigger than Microsoft’s.

Allard had already left on a leave of absence after Microsoft killed his latest project, the Courier, which was viewed as an attempt to compete with Apple’s iPad. Bach will stay through the fall to help launch Microsoft’s big game initiative, Project Natal, which allows you to use body gestures to control games. That project is aimed at taking back the excitement of the industry from Nintendo’s Wii. It may be too little too late. It may be viewed as a copycat. But the lesson for the industry is that they should never ignore the persistence of men like Allard and Bach. The console war isn’t over yet, and Apple hasn’t quite defeated Microsoft either.

Back in 2003, Allard said to his team as they were about to embark on the Xbox 360 design, “If I needed to pick an introductory quote for ‘The History of the Xbox,’ I’d choose the following words spoken by Gandhi: First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.'”

Here’s Ballmer’s memo to Microsoft employees.

From: Steve Ballmer

Sent: Tuesday, May 25, 2010 8:01 AM

To: Microsoft – All Employees (QBDG)

Subject: Executive Leadership TransitionsAfter almost 22 years with the company, Robbie Bach has decided to retire from Microsoft. I have worked with Robbie during his entire tenure at Microsoft, and count him as both a friend and a great business partner and leader. Robbie has always had great timing, and is going out on a high note — this has been a phenomenal year for E&D overall, and with the coming launches of both Windows Phone 7 and “Project Natal,” the rest of the year looks stupendous as well. While we are announcing Robbie’s retirement today, he will remain here through the fall, ensuring we have a smooth transition.

Concurrent with Robbie’s retirement, I am making several organization changes to ensure we have the right leaders in the right positions as we set ourselves up for the next big wave of products and services. Effective July 1, Don Mattrick, who leads our interactive entertainment business, and Andy Lees, who leads our mobile communications business, will report directly to me. Don and Andy have built out strong leadership teams and product pipelines, and are well-positioned for the years ahead. Independent of Robbie’s decision, J Allard (currently serving as senior vice president of Design and Development for E&D), will also be leaving Microsoft. Given his ongoing passion and commitment to Microsoft, he will remain as an advisor to me, helping incubation efforts, looking at design and UI, and providing a cross-company perspective on these and similar topics. With J’s change in role, corporate vice president David Treadwell will join IEB to lead the core technology organization, reporting to Don. David has a great set of accomplishments at Microsoft, most recently working on the Windows Live Platform Services team. Over the next several months, Robbie and I will work together to finalize reporting and structure for the rest of his org.

Now that Office 2010 has been launched to business customers, Antoine Leblond, senior vice president in the Office Productivity Applications Group, will take a new role as senior vice president for the Windows Web Services team. This team brings together the integral Windows services that today deliver updates, solutions, community and depth information for the Windows consumer. Kurt DelBene, senior vice president in the Office Business Productivity Group, will take on all of the engineering responsibilities for the Office business.

Transitions are always hard. Robbie has been an instrumental part of so many key moments in Microsoft history — from the evolution of Office to the decision to create the first Xbox to pushing the company hard in entertainment overall. J as well has had a great impact in the market and on our culture, providing leadership in design, and in creating a passionate and involved Xbox community, and earlier being at the center of our work seizing the importance of the Web for the company. But most important, both have been great team builders with a strong record of attracting, coaching and growing talent. As a result, their teams are primed to continue to step up and deliver great products, great services and great results for the company. Don has led the Interactive Entertainment Business since July 2007, where he’s significantly grown our entertainment footprint as well as our profitability. He can count as successes the evolution of Xbox Live, the launch of blockbusters like “Halo 3” and the much-anticipated “Project Natal.” Previously, Don was president of Electronic Arts Worldwide Studios. Andy has led the Mobile Communications Business since February, 2008, and has been instrumental in reinvigorating our mobility efforts, bringing in new business and development talent and overseeing the creation of both KIN and Windows Phone 7.

As we finalize and ship so many of our key products (“Project Natal,” Windows Phone 7, Office 2010, Windows Live Wave 4 and others) it is a natural time for us to look ahead and make sure we have the right talent in the right roles to fuel our next set of offerings. I am confident that the changes above will set us up well for the months and years ahead.

I want to close by thanking Robbie for the incalculable contributions he has made to Microsoft over the years. He will be greatly missed when he retires this fall, and I am glad that I’ll have the opportunity to continue working closely with him between now and then. And as J makes a similar transition, I look forward to working with him in a new way.

Steve

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More