“Minimum” is not a word usually associated with a good product. But the term “minimum viable product” (MVP) is thrown around as widely accepted advice for startups. Is there truth to it, or is it just another passing trend?

Even how to use an MVP is questioned. The level of quality, the time spent before release, the customer feedback. Everyone has different answers. But which answer will work for you?

Exceptional always beats minimal

“MVPs kinda suck,” says Rand Fishkin, a cofounder of Moz. Like many other entrepreneurs, he doesn’t believe in releasing a lesser product, no matter the benefit, and should focus on EVPs: exceptional viable products.

To do that economically, Fishkin suggests creating an MVP but not releasing it publicly. Instead, keep it in-house, dogfood it with your team and maybe a few select customers, and compile your data that way. Fix the bugs, discover which additional features would help, and only when you have something “exceptional” do you release it to the public. “Don’t be minimum,” Fishkin told us. “Be exceptional.”

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

It’s a strategy I’ve become very familiar with recently. At UXPin, a wireframing and prototyping company that I work at, we started back in 2011 making paper prototyping notepads for designers, our MVP for testing if designers needed a simpler solution for wireframing and prototyping.

Because we didn’t know anything about EVPs, we went through multiple versions. Thinking back now, our MVP really was an EVP, because the paper notepad was a small product idea (not even terribly sophisticated) executed with extreme thoroughness. By focusing on quality over scope, we were able minimize our resources and still get cleaner feedback on our hypothesis.

Above: The problem with minimum viable products, according to Rand Fishkin

The economics of cake-baking

Brandon Schauer, chief executive of Adaptive Path, explains two drastically different strategies for startups regarding MVPs.

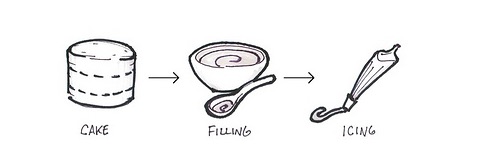

In the Dry Cake model, product teams start with a basic and uninteresting product — like a plain dry cake. Then, as their resources expand, they add new features such as icing or filling. While it makes sense operationally, it’s problematic from a competitive and customer perspective. As Schauer puts it, “cake with no filling or icing isn’t that appealing.”

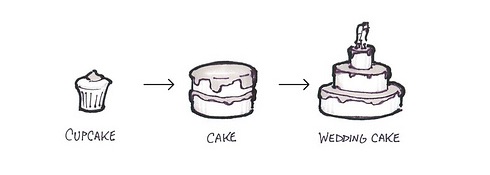

In the Cupcake model, which echoes Fishkin’s EVP concept, product teams start with a smaller yet complete product that is more desirable. It has all the appeal of a complete cake — icing and filling, etc. — but its production costs are much lower. People want a complete product, and they’ll pay for it.

In “The Guide to Minimum Viable Products,” we describe how Groupon — a model cupcake model — started as a WordPress blog and hundreds of manually emailed PDFs. When enough people signed up for a deal on the WordPress blog, founder Andrew Mason’s team would manually send them the coupons via Apple Mail. It wasn’t pretty, but it was a complete product that delivered the same value as today’s Groupon.

Customers crave completion

Quality is a necessary trial for any company. One must understand the user, consider every aspect of the product, and capture users’ loyalty. This requires building a complete product as the first version, an EVP, that can be expanded and improved continuously. If you’re building a partial product with the plan of adding distinct layers on top later, then you’re making a dry cake and should get used to the taste — you’re going to be eating it for a while because no one will buy it.

Jerry Cao is a content strategist at UXPin, where he develops in-app and online content for the wireframing and prototyping platform. He recently co-wrote “The Guide to Minimum Viable Products.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More