A succession of high-profile founders recently threw in the towel, making January seem like a hell month for startups.

In the course of a single week, Outbox’s cofounders published a blog post explaining the holes in their business model, and DrawQuest’s founder and serial entrepreneur Chris Poole admitted that he couldn’t “crack the business side of things” in a post entitled “Why my Startup Failed.” In mid-January, CarWoo and Prim also shut down. These founders were all open about their shortcomings; Prim even agreed to a “postmortem” interview with Fortune.

I developed an armchair theory about this: At the end of December, most founders are forced to take a break from work to go home and visit family for the holidays. This is often a time for quiet reflection. Surrounded by loved ones, we’re more likely to face up to some harsh realities and plan for the future — and that’s just what these founders did.

But was my theory right?

Data scientists from Mattermark agreed to help me test this hypothesis. Mattermark is a new service designed to help investors and the press track thousands of fast-growing startups. The team pulled data from a variety of sources, including but not limited to social media, app store rankings, Alexa.com rankings, AngelList, and news articles.

Incidentally, Mattermark’s chief executive Danielle Morrill is a major advocate for transparency and has been tracking startup failure for years. She posted one of the original postmortems when her previous startup, Refer.ly, shut down. Morrill owned up to her mistakes before closing up shop and laying off staff.

MORE: In a town of gamblers, Mattermark is counting cards

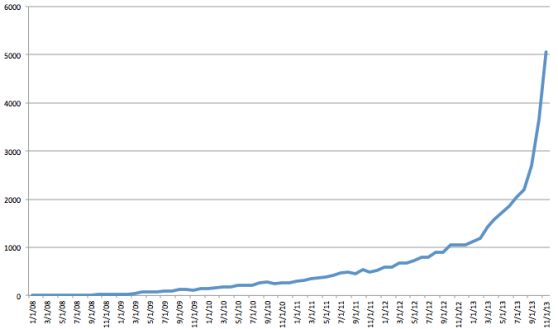

As it turns out, my presumption was completely incorrect. January was not an outlier month. Mattermark chief technology officer Kevin Morrill said the data is more limited than he would like. However, he was able to pull some closure dates from Twitter (based on when startups stopped using their accounts) and Crunchbase.

“Of the data I found, it does not demonstrate a big closure rate coming out of Christmas and New Year’s,” he said. If anything, Morrill noticed a slight bump in closures in September and October. Neither of us has a particularly sophisticated explanation for that.

What changed in January wasn’t an increase in failed startups. It was that more founders took the time to publicly acknowledge their failure and notify the press. Outbox’s (now former) public relations firm communicated with us immediately after the company shut down. Indeed, radical transparency is increasingly the norm in Silicon Valley, Austin, and other tech hubs around the country.

Learning from mistakes

A research firm called CBInsights recently published some analysis on startup failure. Its team of data scientists and analysts concluded that most startups die 20 months after raising financing after raising about $1.3 million.

Why are some of these founders opting to speak out about their failures and not others? A post-mortem post has become increasingly common, particularly given the voracious demand for this kind of content. Andy Sparks (who now works for Mattermark) wrote a four-part series on the topic of failure on his blog, which generated an immense amount of traffic. In part IV, dubbed Recovery, Sparks compares the experience to a bad breakup.

Authors like Sparks seem to be driven by a genuine desire to help other founders avoid the same mistakes.

These post-mortem posts should be required reading for any tech entrepreneur, as they contain practical advice. Outbox’s cofounders describe in detail why their partnership with USPS never quite worked. It’s a worthwhile read for any entrepreneur who is attempting to build a relationship with a government agency or institution.

Sonar’s founders write in depth about how to incorporate feedback from users and the activities they wish they’d spent less time on.

Decide.com’s cofounder advises against hiring too many people early on; “2 or 3 people can get a lot done,” writes Hsu Ken Ooi.

Other founders have spoken up about their experiences raising capital from parents, angel investors, or venture capitalists. This post from Canadian entrepreneur Ben Yoskovitz is particularly worth a read for anyone who’s in the process of fundraising.

Keen to read more post-mortem posts? Researchers at CBInsights have put together a useful list of quotes and lessons learned from founders of failed startups.

Taking the stigma out of failure

It’s cathartic for founders to write about their challenges running a business and dissect what went wrong.

Some people have a tougher time recovering from failure than others. It’s not uncommon for entrepreneurs to feel depressed for months after a startup shuts down. The winding down process typically involves firing employees and notifying investors that their money will not be returned. Losing the savings (and potentially even respect) of people you admire cuts deep. It can also be a major financial setback. Founders often move back in with their parents while they plot next steps.

That said, posts like “7 lessons I’ve learned from a failed startup” make closing up shop seem character-building. The founder writes that he’s “proud” and that failure isn’t something to be ashamed of.

This represents an important shift, one that mental health experts have been advocating for years.

A discussion about the psychological effects of failure was thrown into the public consciousness after the tragic suicide of Ecomom founder Jody Sherman. A year prior, Ilya Zhitomirskiy’s suicide ignited a similar discussion about the mental health repercussions of extreme pressure and scrutiny. Zhitomirskiy died at 22 years old after cofounding a startup that was positioned by the press as the “anti-Facebook.”

“They [entrepreneurs] find themselves on a road where their life becomes very focused on one thing,” said Michael Groat, a practicing psychiatrist at Baylor College of Medicine in a recent interview with VentureBeat contributor Sarah Seegal. “When this thing collapses, people can be very vulnerable to collapsing along with it,” he said.

MORE: For young entrepreneurs, the price of a startup could be your mental health

Reading and writing a post-mortem blog post is a positive exercise in and of itself. I also noticed that the comments were largely optimistic. Founders who are feeling alone often gain support from the community.

“I can definitely tell you it felt cathartic to just be open, and people were extremely kind and supportive,” Danielle Morrill wrote to me.

Advice from the experts

Postmortem posts are increasingly the norm, but would the experts advise writing one if your startup fails?

Some founders, like Chris Poole, admit that they aren’t yet clear whether they’ll start another company anytime soon. Meanwhile, Outbox’s cofounders are already hinting at a new venture. For entrepreneurs who are keen to give it another shot, will a postmortem post work in their favor?

I asked investors and public relations experts in my network for their thoughts and received some highly detailed responses. Investors, in particular, are eager to share their thoughts.

Investors: Authenticity is a virtue

“I am a firm believer in the reality that no one ever succeeds at everything – at least on the first try — and that the only real failure is one that you learned nothing from,” said Cindy Padnos, an investor at Illuminate Ventures.

But Padnos wouldn’t jump to a postmortem post in every case:

“I suppose I would hesitate to do a blog or press release until the founder was sure of his/her next steps,” she said. “Do they think they have something they can resurrect or is this really the end? Do they sell to business users who might be scared off by admitted failure – or to consumers who are likely to give their reformulated offering another shot at success?”

Emergence Capital’s Kevin Spain wouldn’t be more likely to take a meeting with an entrepreneur who has been honest about failure. But he wouldn’t shy away either.

“In general, I tend to prefer entrepreneurs who are authentic and transparent,” he said.

Ravi Belani, who runs an accelerator program for entrepreneurs, said he thinks we should be transparent about both failure and success. Belani said that the tech media hasn’t done a stellar job of getting across how difficult it is to run a company. Some entrepreneurs give up when they realize it’s an Everest; others keep going.

“If we are truly being radically transparent, the reality is that great entrepreneurs face the brinks of failure and all the hardships — and persevere. Often they are driven by something irrational, passionate, even maniacal. And often they know how to master market timing where others don’t,” he told me. “Instead of glossy stories of raising big Series A rounds, [I would like to read about] the deeper truths on what were the underpinnings of that success.”

Public relations experts: The story will get out anyway

I expected public relations folks to shy away from encouraging founders to be transparent around failure. Most press releases that hit our inbox involve offers to speak with a CEO of some company that just won an award or landed some corporate big fish as a customer.

But failure — it’s not often we receive proactive pitches from entrepreneurs willing to chat about their struggles.

However, Kevin Cheng, a director at SparkPR, said radical transparency isn’t something he’d advise against. Cheng said he would encourage a CEO to think deeply about the value it would bring to employees, partners, and customers.

He said founders should question whether others in the industry will benefit from a detailed perspective. “For the majority of startup failures, the news is going to get out no matter what, so being proactive allows a CEO to shape their message and bring valuable context to the businesses’ hardships,” said Cheng.

Likewise, Jesse Hamlin, an account manager at another tech-focused public relations firm, Eastwick, had some advice to share. Hamlin said she would ask founders the following questions: Are you actually pivoting or actually closing? Did you tell everyone that matters first? Are you writing the postmortem because people want to know or because you want to tell them?

“I don’t think that radical transparency is an excuse to air grievances or explain what didn’t work or pat yourself on the back,” said Hamlin. “There should, however, be an option to contact the CEO/ founder if people do have questions, and you should be prepared to answer those questions.”

A well-written postmortem post can be a saving grace for any entrepreneur. It’s a means to rally community support, face failure head on, and it puts the author in a strong position to try again.

An estimated three out of every four venture-backed startups shut down, according to research published in September of 2012 by Shikhar Ghosh, a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School.

At the time, Ghosh accused most investors of “bury[ing] their dead quietly.” But founders are increasingly speaking up, making that buttoned-up and conservative approach seem like a thing of the past.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=44ebf696-c185-45ba-9fef-0fb5618596d3)