[Update: We modified the wording in this story from “Native Alaskan” to “Alaska Native” people. The term Alaska Native represents 11 distinct cultures and languages, and 22 different language dialects. A native Alaskan, on the other hand, is any person born in Alaska.]

The makers of Never Alone want to make it an unforgettable experience not only for video game fans but for the Alaska Native group whose mythology it captures.The rare collaboration of video game veterans and the Iñupiaq Alaska Native group is aimed at preserving the culture of a native people and communicating it to its youngest members as well as the larger world.

The title is a major production, financed by the tribe, and is coming this fall as a $15 downloadable game for Steam, PlayStation 4, and the Xbox One via the Unity 3D platform. The venture has worked out so well thus far that Upper One Games and E-Line Media merged this summer to create “World Games,” or projects similar to Never Alone in celebration of indigenous cultures. Upper One Games is now the label of E-Line Media, which is based in New York and has a development studio in Seattle, and it will focus on games based on cultural storytelling. It is a blend of a commercial enterprise and cultural education.

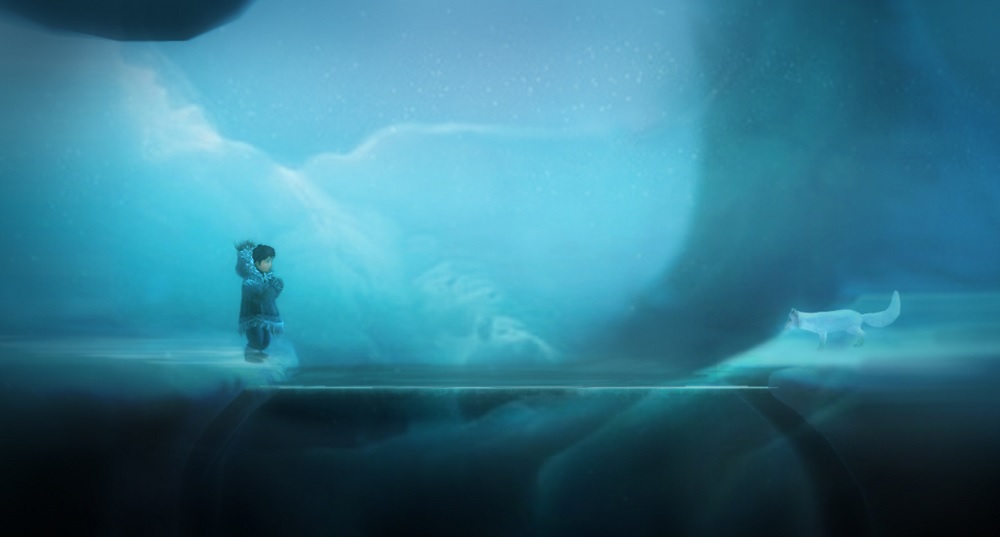

Never Alone (also known as Kisima Ingitchuna in Iñupiaq, a language of the Alaska Native people who live north of the Arctic circle) is about the journey of a young girl, Nuna, and her companion Arctic fox who journey into the world to find the source of a menacing blizzard. The game is a two-dimensional puzzle platformer that combines traditional folklore, stories, settings, and characters handed down over many generations by the Alaska Native people whose heritages dates back millennia. The art and themes are drawn from Iñupiat (the plural of Iñupiaq) and other Alaska Native cultures.

Sean Vesce, the creative director at E-Line Media and a video game industry veteran, said in an interview with GamesBeat that his team made a dozen visits over the past couple of years to Alaska to hear the stories directly from master storytellers.

“It’s been a labor of love, exploring an indigenous culture and its values and themes,” said Vesce, who has worked on Tomb Raider and MechWarrior games in the past. “The tribe has been involved in the development of the game every step of the way. All constituents helped to make the most appropriate and interesting game we could make.”

Alan Gershenfeld and Michael Angst, the cofounders of E-Line, met with Amy Fredeen and Gloria O’Neill of the Cook Inlet Tribal Council in Anchorage, Alaska. They had the foresight to see that video games could be a good way to preserve the culture of the tribe and dispel stereotypes about Alaska Natives. They also saw the game as a path for self-sustainability for the CITC, which has been funded by government grants in the past. The CITC and E-Line carved out a partnership and work on the video game began with a team that included tribe elders and storytellers.

Fredeen, who serves as chief financial officer and executive vice president of E-Line Media, said in an interview, “This is totally out of the box for us as an organization and as a people. We were asking ourselves what will connect with our youth, who face a lot of harsh statistics.” She said that Inupiat youth are twice as likely to commit suicide, and less than half are graduating from high school. There are high rates of alcoholism.

“There are negative statistics hanging over their heads and we wanted to give them something positive,” Fredeen said. “We wanted to give something cool to them and the rest of the world. When they share this game, they can be proud it is being shared by the rest of the world.”

Elders, many who had never played a video game, recognized that their grandchildren and great-grandchildren were playing games. So the group used its savings and money from the Rasmuson Foundation to fund the project.

“It’s been a phenomenal process because Sean’s team has been so careful about including people in the process, and not just as a rubber stamp,” Fredeen said. “Coming up here 12 times has demonstrated to the community that they want this to be authentic.”

One sign of that authenticity is the alternative title to the game. Kisima Ingitchuna means “I am not alone” in the Iñupiat language. The phonetic pronunciation is “Keeseema Eengeetchuna.”

Nearly three dozen Alaska Natives worked on Never Alone. The team wanted to create a game where the theme emphasized working cooperatively to overcome challenges in harsh environments. The game promotes interdependence, as manifested in the cooperation of the girl and the fox. The group values subsistence hunting and fishing, and a deep connection with nature, as a way of life.

Another of Never Alone’s theme is resilience, the capability to survive in one of the most difficult environments without giving up. The last major theme is about intergenerational exchange, or the passing on of wisdom from one generation to the next. One or two people can play Never Alone at the same time. “That makes this the perfect game for parents to play with their children, or siblings to play with each other,” Vesce said.

The game’s tale comes from Inupiaq storyteller Robert Cleveland, whose daughter, Minnie Gray, did interviews with Vesce’s team. She gave permission to adapt the story for the game. Ishmael Hope, a member of the group, was one of Never Alone’s main writers.

“These stories are so fantastical that it wasn’t hard to make a fun game,” said Vesce. “Many of the actions described map perfectly to gameplay.”

It was a little harder to visually depict the “helping spirits” of Inupiat culture as ghostly figures who provide aid. The fox is able to reveal these helping spirits to Nuna. Both the fox and the girl complement each other, as each can do different things.

“We had to create a look and feel in a way that wasn’t overly romanticized but resonated with people whether you were inside or outside the culture,” Vesce said.

Fredeen said that the selection of the narrator generated discussion. The CITC contributors wanted to make sure that they had someone with an Iñupiaq accent for the voice narration. Some actual voice playbacks of tribal storytellers will serve as some of the rewards inside the game. Vesce’s team recorded around 40 hours of video with the tribe’s storytellers.

“We worked with Sean to work with an elder that fit well,” Fredeen said.

The team also talked a lot about the companion animal, as the local custom had to be in balance.

“The process has been one of the great joys for us as game developers,” Vesce said. “We are using our skills to further the goals of a community, and to learn.”

Whether the game succeeds or not, Vesce said it is already the most rewarding project he has ever worked on.

Never Alone – The Power of Videogames from Never Alone on Vimeo.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More