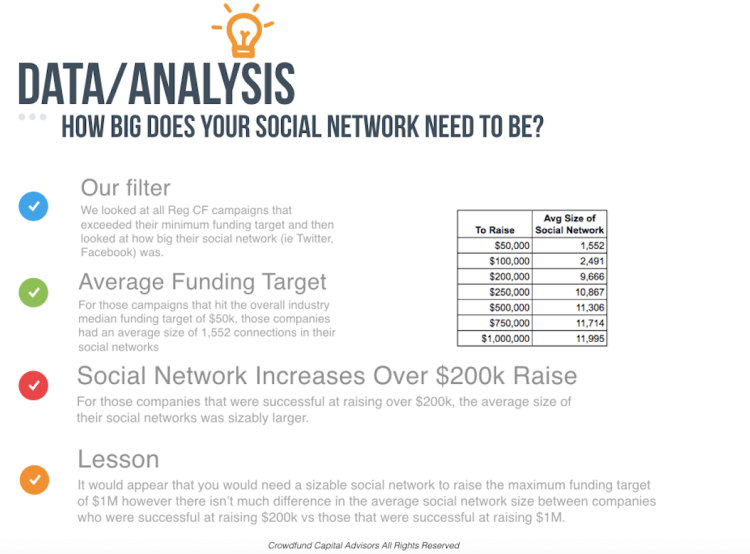

Five and a half months after the SEC began allowing crowdfunded investments for startups, it’s apparent that it pays to be popular. Entrepreneurs with the largest social networks have tended to be those who raise the most capital — even if the total amount of capital raised under the nascent Regulation Crowdfunding program is tiny. Of the $6.7 million funded thus far, entrepreneurs with fewer than 2,500 social followers have raised less than $100,000 in their individual funding efforts, while those with about 10,000 followers have raised between $200,000 and $1 million each, according to Crowdfund Capital Advisors, an investment advisory firm.

To implement Title III of the JOBS Act (officially known as The Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act), the SEC began permitting entrepreneurs to seek equity investment via Regulation Crowdfunding on May 16, 2016. While the law provides specific guidelines about disclosure and transparency, in many ways new regulation simply updates for the digital age the friends and family-type financing common among small businesses and first-time entrepreneurs.

“This is a new way to do an old thing,” said Sherwood Neiss, a principal at Crowdfund Capital Advisors, in an interview with VentureBeat. Neiss had helped lobby Congress for passage of the JOBS Act and is a leading advocate for crowdfunding. “Entrepreneurs have always raised money from people they know, usually based on pre-existing relationships.”

Social networks like Facebook and Twitter have expanded the pool of potential investors beyond geography to communities of interest, shared national origins, and so on, in ways that previously were not possible. Still, Neiss estimates that 90 percent of entrepreneurs who’ve received crowdfunded investment had a pre-existing relationship with their investors.

Crowdfunded equity investing is distinct from your typical Kickstarter or Indiegogo campaigns, which are often thought of as donation- or awards-based efforts. The key difference is that backers receive equity in exchange for their financial support, which incurs a series of regulatory requirements.

First, there’s a cap on the funding amount. Under Title III, entrepreneurs can raise up to $1 million in a 12-month period from ordinary investors. Then there’s the paperwork, which some critics have called burdensome and which may be a factor in the program’s slow start. (Other critics warn that the JOBS Act will usher in fraud and undermine the venture capital industry.) Entrepreneurs must register their fundraising campaign with the SEC, abide by strict limits on solicitation, and provide a range of disclosures. It’s the restrictions on solicitation that make the size of an entrepreneur’s social network a critical factor for successful fundraising.

Neiss and his team have seen positive signs for the new regulation during its first five and half months. They culled data from 5,200 fundraising efforts filed with the SEC under the JOBS Act, and analyzed the 144 companies that have specifically filed for Regulation Crowdfunding since May 16, 2016. Of those, 46 reached their deadline to hit their minimum funding target. And 22 of those 46 were successful in hitting their minimum funding target. Some of the key findings, according to Neiss:

- Total number of individual investments: over 14,000

- Average number of investors per deal: 268

- Average investment per investor in successfully funded deal: $879

- Average amount of successful raise: $239,155

- Average valuation: $4.98 million (outlier valuations of $32.4 million and $56.3 million removed)

- Total capital committed to date: $13.6 million

- Total capital funded (meaning campaigns that hit their minimum funded target and closed) : $6.7 million

While it’s too early to draw many conclusions from this very small data set, Neiss says that the popularity of revenue-based financing is one metric that stands out among the successful deals. Thirty-nine percent of the nearly $7 million raised to date under Title III went to entrepreneurs who offered this arrangement. “Investors start getting paid back immediately,” said Niess. “It’s the JOBS Act’s secret sauce.”

While it’s too early to draw many conclusions from this very small data set, Neiss says that the popularity of revenue-based financing is one metric that stands out among the successful deals. Thirty-nine percent of the nearly $7 million raised to date under Title III went to entrepreneurs who offered this arrangement. “Investors start getting paid back immediately,” said Niess. “It’s the JOBS Act’s secret sauce.”

Under revenue-based financing, entrepreneurs set aside some amount of quarterly revenue (say, 5 percent) and distribute it to investors over a set period of time (say, four years) until an agreed upon return is reached (say, 1.5x or 2x). It’s long been a common vehicle for small businesses, but the JOBS Act allows entrepreneurs to pursue it with several hundred investors instead of perhaps a dozen family and friends.

While crowdfunded equity’s revenue-based financing is different from typical venture funding arrangements, the measure of its overall success will be the same. In the investment game, it’s all about exits and returns. In many cases, that will mean waiting five to seven years to know whether that $879 from a “mom and pop investor” helped launch the next Facebook or Google.

Neiss also draws another distinction from traditional venture capital. For entrepreneurs pursuing Sand Hill Road funding, having a great team, a great product, and a great business plan may be enough. But for entrepreneurs seeking Regulation Crowdfunding investment, he sees an additional requirement. “If you’re going down the path of raising money from the crowd,” he cautioned, “Do not do so until you have a strong social following.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More