LAS VEGAS — It’s been more than a decade since 9/11 brought a stringent screening process to all airports. But can someone still get a weapon through Transportation Security Authority (TSA) airport screening devices? Yes, according to a security researcher who found flaws in three security machines.

Billy Rios, director of threat intelligence for the large security tech firm Qualys, said in both a press conference and presentation that he was able to find flaws that would enable a bad guy to spoof a machine and trick it into giving a wrong reaction when screening for weapons.

In his talk, Rios noted that he did the research on his own time, and reported all the problems he found months ago. Some of the devices are not in use anymore, but they illustrate the lack of thinking when it comes to device security, Rios said.

Rios made the presentation at the Black Hat security conference today in Las Vegas. Black Hat talks are normally alarming, as security researchers have found it all to easy to poke holes in computer-related devices.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

But Rios, a former lieutenant in the Marines, said he has found a disturbing pattern among the makers of embedded appliances, or those that have computing equipment inside them but operate as stand-alone appliances, rather than full-fledged programmable computers. He said that equipment makers routinely leave “backdoor” passwords inside the machines for technicians to access and do maintenance.

“There is a pattern of this in embedded devices,” Rios said. “A service technician has backdoor passwords. It’s a common dangerous thing among devices. Anyone doing embedded research for security will find it.”

Rios found a lot of the information out in the open. The TSA has a 153-page document, Checkpoint Design Guide, on the web that describes how to properly set up a security screen at an airport. It has pictures of equipment used, diagrams of the networking layout, and other details that hackers could make use of.

“It has excruciating details, pushed out from a central authority,” Rios said. “Even the bins have to be done in a certain way.

The devices Rios investigated were the Morpho Itemsier 3 explosive trace scanner, Kronos Terminal time clock, and the Rapiscan X-ray machine. The machines are all connected to a network dubbed TSA Net.

“I never gained access to the TSA Net, because if I did, I would probably be in jail,” Rios said.

Rios ordered several of the machines from different manufacturers and found that they had poor security. One of the machine’s from the Morpho division of French conglomerate Safron is called the Itemsier 3 trace detector. Thousands of the x86-based machines have been sold to the TSA and others, but the Itemsier 3 was discontinued in 2010, according to Karen Bomba, president and CEO of Morpho Detection, in a statement. Airport security use the machine to detect explosive traces on the hands of people being screened.

Morpho responded to Rios’ discovery of a bug by saying it would patch its software by the end of the year. A spokesman for Morpho acknowledged that the bug was related to leaving a backdoor for a technician. That bug, Rios said, could enable someone to take control of the machine and compromise it. They could, for instance, trick the machine into generating the wrong response.

Rios ordered a Morpho machine, which can detect explosives or illegal drugs, and had it shipped to his house. He disassembled it, identified the chip where the software was held, removed it, and then analyzed it with a common diagnostic tool. He found it alarming that the machine had the backdoor that could be so easily hacked.

The breach in security was serious enough for a ICS-CERT security alert about the Itemsier 3 to be sent out on July 24. Can the vulnerabilities be used to get a weapon past TSA? Unfortunately, yes, said Rios.

Rios believes the machines he found flaws in are widely used, but he couldn’t do more research without violating the law. While Morpho responded to his queries, the other companies did not, he said.

The TSA had a budget of $7.39 billion in 2014, and it employs more than 50,000 people at 400 airports through the country. They screen 2 million people a day. About $250 million a year is spent on security equipment. The first response Rios received from the TSA was “our software cannot be hacked or fooled.”

Rios said he does not know if the TSA has patched the security issues already.

Backdoors are secret ways to access software in a device. They are often malicious accounts added by a third party. Rios hasn’t seen those in his research of TSA equipment. But he has seen debugging accounts that some people forget to remove, and he has often seen technician accounts that are often hard-coded into software.

The problem is the backdoors can be discovered by external parties, like Rios. They often can’t be changed by the end user, and once the passwords are broken, they often work on every machine.

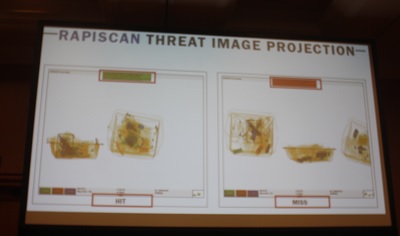

With Rapiscan, once Rios gained access to the password, he was able to look up the passwords of other users. TSA canceled the security contract with Rapiscan in 2013.

The Kronos device ran Java code and it actually had a password for a super user. Rios figured out that a particular machine was being used at San Francisco International Airport at one point. The device was subsequently taken offline.

Rios said the responsibility for fixing security lies with TSA, as vendors will build their machines to meet its specifications.

Rios said he hopes that someone verifies that TSA’s security is good, and that all makers of embedded devices take note of the vulnerabilities.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More