Above: In five years, a digital guardian will protect you online.

VB: Number four, “a digital guardian to protect you.”

Meyerson: That’s pretty funky. Something on the order of 12 million people a year in the U.S. get their identities stolen. It’s ridiculous. The thing is, unfortunately, a lot of folks – because you have to be pretty tech-savvy – don’t know what to do when they get a URL in their e-mail that says it’s their bank and there’s a problem with their account. Next thing they know, a site comes up that looks a lot like their bank, and it asks for their password and ID and they figure they’re logging on. What they’ve just done is given some hacker all the information they need to empty their account. And the reason is that they don’t know what that URL really means.

That’s the sad truth of the web. Thieves take advantage of the fact that most people are inherently good and trusting. But you shouldn’t have to become a cynic. What should happen is that there should be really robust ways of protecting people. You have people using all kinds of digital means to rip folks off. Why don’t we use digital means to protect them?

The fascinating thing that’s happening now is that we’ve figured out that most malware and viruses and can be contained with the use of good software. Various companies sell that. The problem is that now the bad guys have figured that out, so they resort to techniques that lie outside of what those kinds of protections can discover. They don’t write a virus that makes you system do something bad. Instead, they’ll send a phishing e-mail or a bad URL. You can’t look for the signature of an attack in that.

In the old days you’d look for the signature code of a virus and presto, you killed the virus. Nowadays you have to figure out ways to look at the behavior of systems. With processors becoming more powerful over the last couple years – and they’re now found in handheld devices, from Samsung or Apple or whoever else – those processors have enough horsepower to do some very clever things. You look at the behavior of the device you have, all the connections it’s making, and you spot anomalous behavior.

You’re not looking for a particular piece of code. This machine protecting you looks in detail at your normative behavior, and it starts screaming when it sees something out of the norm. When it sees you clicking on a website where the image name of what you click on is not the same as what you arrive, it screams at you, “Stop, this is bogus!” Or when you read a phishing e-mail, it reads it with you and says, “Uh, are you really sure you want to do this?”

It’s not something where a third-party is getting your information and doing this for you. This is your agent – again, your persona writ large, because of the tremendous compute horsepower available these days. It’s a bit like having Jiminy Cricket on your shoulder, armed with a bat with a spike in it.

VB: “Guardian” suggests something you trust. If you can’t trust yourself, you can trust somebody who’s better at this stuff.

Meyerson: What you’re doing is trusting a digital persona. This is a smart learning system. It learns your behaviors over time, takes that learning, and notices when you’re doing something abnormal. That makes it a powerful weapon against the bad guys. The bad guys have an awful day when you can instantly recognize that they are the bad guys. You recognize them for what they are and shut them down before they get into your account.

VB: The smarter bad guys seem like the ones that would take a dollar off your credit card every month, instead of the ones who empty your bank account.

Meyerson: That’s true. There are guys who do that. The catch is, if they’re doing that, it doesn’t fall within the norm either. If they take a dollar out and it says it’s going to some business name, this guardian has nothing better to do than look at everything you do – everything – and look into where that dollar’s going. It’ll track it back to where it arrived and say, “Does this make sense, that it’s going to God knows where? I don’t think so.”

The point I’m making is, again, it’s not a normal behavior. You’re right that they can do this, because as a person you wouldn’t recognize it. But this machine will spot it because it traces it to its destination, and if it says it’s doing X for you, the machine will find out what X is. X, of course, won’t check out. It won’t correspond to anything you’ve otherwise interacted with. This thing will be a detective and you don’t have to do anything.

The other thing that happens, by the way – and we have systems like this already – IBM has a smart system called QRadar. It looks at every connection being made to everything from a given set of IP addresses. It can spot behaviors in the thing you connect to that are already suspect and set off an alarm. But it’s not just an alarm that goes to you. It goes to everyone going to that address. Once you know that’s a bad address, it instantly tells the planet, “Hey, look out for this.”

The reason bad guys get away with what they do, even if I can spot a scam email, the sad part is, there will be someone who just might not be paying attention. But any time somebody flags one of these things as bogus, because these entities talk to one another, they collaborate and say, “Put a check on this.” You don’t have to go look on some list of scam emails. It will be your guardian. Its job will be to scan the web and scan sites that identify these kinds of phishing expeditions and know in advance if you’re being targeted.

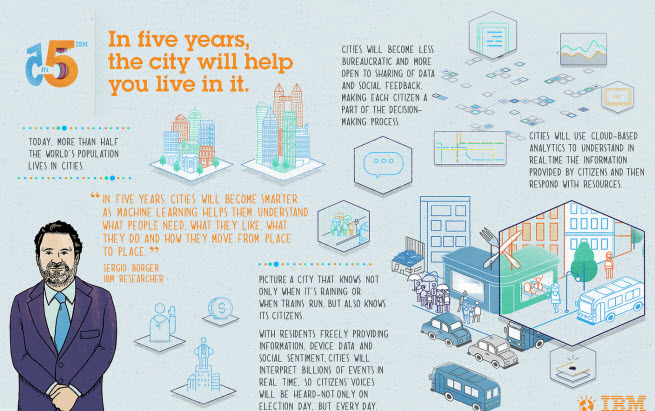

Above: In five years, the city will help you live in it.

VB: For number five, the smart cities, the thing that came to mind was—I wonder what you thought about this video game called Watch Dogs. The premise is that cities have become smart, and then a hacker hacks into them and controls the city. He uses the ability to find out about everybody for his own sort of nefarious ends. At the same time, he’s fighting against some kind of NSA-like organization. It’s a very big game coming from Ubisoft in 2014. It’ll raise the awareness of smart cities in that respect. It’s all about what goes wrong in a smart city.

Meyerson: I hadn’t heard of that. But here’s the deal. Given that there’s a trillion dollars moving around on the web through online shopping—You’re already there, in so many aspects of your life. The diversity of the city is such that you’re already there. I’d much rather have the city linked and be one integrated entity. The reason being, then I can protect it.

You already have your electronic controls in power plants. You have the pumps that move sewage for cities like New Orleans, below sea level. I’d much rather have them fully integrated, where I can maintain watch over them and do the same thing. You have an agent that watches the city — no different from the agent that watches you, but it’s vastly more powerful.

Again, it looks for the normative behavior. Some wise guy decides they’ll make the sewage pumps run backwards and make a mess. You’ll instantly pick up on that because it’s not the normal behavior. It instantly shuts down. We’re already in this mode. You can’t change the past. I would argue the best thing you could possibly do is integrate all of this and make sure you’re looking at everything.

Above: Watch Dogs

VB: That one might seem a little far-fetched. But the fact that hackers exist, and that there’s this possibly Orwellian aspect to it—It could make people feel protected, but it could also make them feel vulnerable.

Meyerson: The bottom line is that hackers are a modern-day reality. In my own view, if you look at what the smart city is about to begin with, it’s much less about the physical infrastructure. That’s there already. It’s electronic. If you go into the subway, it tells you that the train is two minutes away, now here it comes. All of that is done.

What we’re talking about way beyond that is a city that becomes fully inclusive. Right now, the feedback mechanisms are awful. If you think about it, what is it? You hate the mayor, so you vote for his successor in a couple of years, at best. This sort of thing is very difficult. There are public meetings, but maybe you work odd hours and you can’t participate in city government by going somewhere remote and sitting down for two hours of folks yelling at each other.

Imagine if you had the ability to instantaneously get feedback from the city’s population on changes you’ve made, because you have a site people can access from anywhere. Or it might not even require the site. Maybe there’s an app – you’re standing on a bus, you bring up the comment app, and now you can make your contribution on the bus. It assumes, based on your position and what you’re doing – in this case, using public transit – that you have a comment. It could be positive, negative, ambivalent. The point is, instant feedback. The ability to make a change in city government and get feedback from the population in a matter of hours or days would be terrific for driving quality of life.

You can quantify quality of life issues like you could never do before. You could ask people for permission to use the microphone in their handset, let’s say, for 30 seconds every hour. It takes the microphone, turns it on, turns on the GPS, and picks up where you are in the city for 30 seconds every hour. By mapping the city’s noise levels through that microphone – just the noise levels alone – you get a quality of life measure.

If enough people participate, you get a sonic map of the city. That alerts you problem areas, where you can set noise thresholds above which you immediately send people to investigate. Similarly, you could follow patterns, where noise is evolving to louder levels every day. Again, it’s the same question. What am I doing wrong?

You can also query people on quality of life measurements. You could say, “What do you think about the quality of life in this city?” And then you correlate that commentary against the local issues in someone’s region. You can decide, from that, where you should make your investments to get the biggest bang for the buck. You may know the noise levels in a region are high, but you also may know that transportation there is very crowded. But by looking at what people themselves value as their biggest issue and getting that accurate feedback, you can make investments with the right priority.

You don’t just have to guess. You can quantify the benefit. That’s a great value, because quality of life attracts people. People, as they move into a city, drive value into the city. The U.S. has a consumer economy. You want to build a city, bring people in. You want to bring people in, improve their quality of life.

I have this old war cry from my days as a hardcore physicist. I always have to remind people. Data wins. A vast amount of time, we make decisions without data. We have a feeling, an opinion. Maybe we’ve gone out and probed some people. But we don’t have hard data. This is a way to get hard data in a time that’s almost unimaginable at present.