Our story on IBM’s predictions for five big innovations that will change our lives in the next five years has turned out to be very popular. So we decided to give readers more of it with this transcript of our interview with the fascinating Bernie Meyerson, the vice president of innovation at IBM. We had a chance to go over each of the five predictions in our talk.

Meyerson said that IBM (whose founder Thomas J. Watson famously predicted that there was a worldwide market for five computers) takes its predictions very seriously, tapping the grassroots recommendations of its 220,000 technical employees and the top-down views of its leadership. Meyerson runs a group dubbed the IBM Academy of 1,000 IBM scientists and also runs liaisons with universities. He is also a pioneer of a chip manufacturing process known as silicon germanium, which combines two different elements to make a very fast communications chip.

So Meyerson knows his tech. He’s also got a good sense of humor. So please check out our interview.

VentureBeat: Tell us about your predictions.

Bernie Meyerson: Setting the right perspective on these things, what we do here in the 5 in 5, we try to get a sense where the world is going with some decent probability. That then focuses where we put our efforts. These are seminal shifts. They’ll drive large chunks of society in a given direction. We want to be at the leading edge with them. Preferably enabling them. That’s what’s behind this. Unless you stick your neck out and say, “This is where the world is going,” it’s hard to then argue you’ll be able to turn around and get there first.

VentureBeat: Have you done this a lot of years in a row, then?

Meyerson: Yes, many years. We’ve been doing this quite a long time, approaching a decade now.

VB: Myself, I would think it would be easier to do 20 in 5. Just spread those predictions out. Some of them will be more likely right.

Meyerson: You’d be surprised. One of the joys of having something on the order of 220,000 technical people, you’d be astonished by the diversity of stuff we hear about. It’s many times not so hard to identify the ones that’ll happen. The harder part sometimes is nailing down what you want to focus on, as opposed to what’s going to work.

You may have seen, we all agree there’s going to be almost a globalization of access to big data and access to analytics that will drive it. Once you have that, what are the impacts? You may start with a single assumption, and from that assumption say, “Well, the consequences are X, Y, and Z.” The societal consequences of that will be enormous.

To some extent, that’s what’s here. What underlies most of these is the fact that we have this enormous investment in data analytics and the handling of big data. What we’re seeing happen is astonishing. The ability, in the past, to understand and get insights from data was a big deal. People talked about data mining and all the stuff you could get out of that. That had virtue, but if you go to the next level, it gets interesting. Then you can start talking about stuff that sounds like science fiction – the ability to not only predict the future, which is what modeling is about, but to change it.

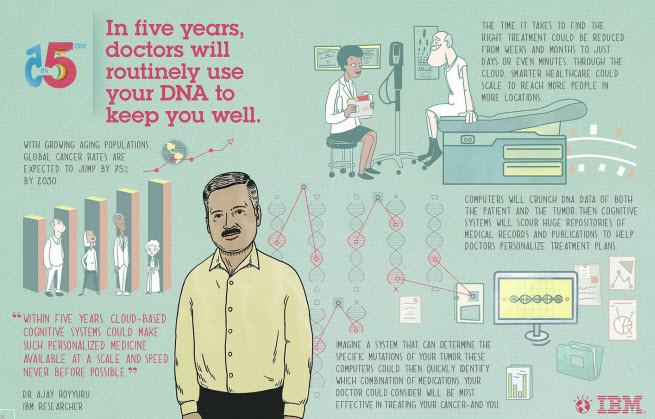

The real-time ability to change the future in an active fashion sounds like science fiction, but now we do it every day. That’s where you start to get into things like—We use the example of the city we help you live in. Think about traffic reporters. They say, “Hi, you’re stuck on the Long Island Expressway.” That’s not an epiphany. You could announce that on any morning at 3AM and be accurate. What would be interesting is making an announcement that says, “Hey, you would have been stuck in a traffic jam now, but I predicted it would happen 20 minutes ago, so I changed the sequence of some lights that feed this road, and so there’s no traffic jam. Have a nice trip.”

That changes the way you live in a city, but it requires you to collect vast amounts of data, build accurate models, and understand the reaction of what you’re worried about to changes. It’s a hugely complex issue. You can’t just do it by licking your finger and sticking it in the air. And that’s one of many examples.

VB: The process for doing this, did you guys discuss them for quite a while?

Meyerson: We do it bottom-up and top-down. The team will go about this for many months on end and we’ll go through and refine it. A lot of people put in their ideas. What you’ll find sometimes is that you see a common theme, and then you look at that theme and realize that it has a massive impact. It’ll be so pervasive that you follow that up and say, “Where does this lead us as far as the areas we care about?”

There’s this great quote from Ann Winblad at Hummer-Winblad — “Data is the new oil. Unrefined, it is of no value. When you refine it, it powers the world.” If you take that at face value, it’s a good explanation of what we’ve been doing for the last 10 years. We didn’t spend $25 billion, between internal and external work, on analytics without good reason. If you believe data powers the world, you have to understand and extract insights from it and act upon them. But where do you do it? All these are examples of where you do it.

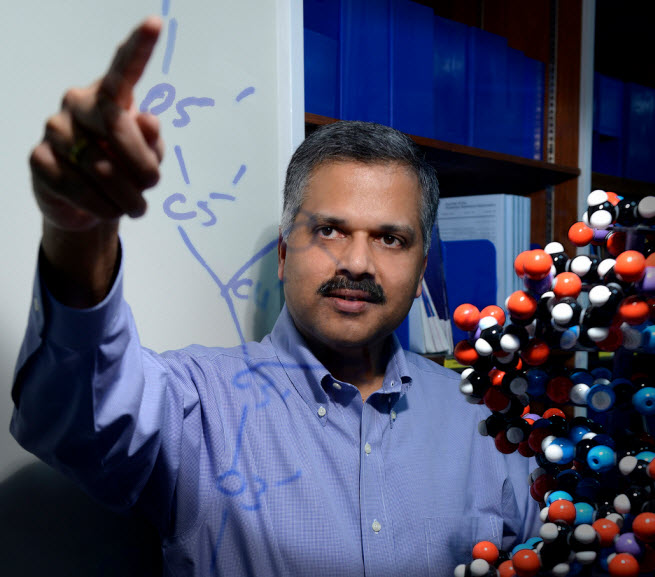

If you look in the classroom, a typical student starts every year cold. Most teachers have never seen the kid before. You have a cold start and no background or relationship every time you begin the school year. What would happen if it was all captured and you had an electronic persona that followed you through your educational cycle? People know your strengths, your weaknesses, where they should apply more help to get you through areas they know you’ll need help. At the same time, places that you excel, they could challenge you with better materials.

Think of the ability for a classroom to operate so that every individual child has instantaneous attention from a system that recognizes immediately that they’re struggling with a concept, and feeds that back to the teacher – “This person needs help in this regime.” Even better, when you have people who come up with new schemes for educating in a particular area, you can get feedback on how it works in a matter of instants.

VB: So schools making use of data, is that essentially what the first of the 5 in 5 is talking about?

Meyerson: Yeah. Not only does the school collect it, but it uses it in real-time and on an ongoing basis to create a persona, so that you don’t lose history. What you’ve been challenged by, everyone’s aware of it, and they can make sure that going forward you don’t have an issue. It’ll pick up problems like dyslexia instantly, because you’ll see when a child is reading and there’s an inversion of meaning. You make sure that if a child has areas where they have extraordinary abilities, they’re recognized and catered to on an individual basis.

No one teacher—You look at classrooms of 30 kids. A teacher cannot do it all themselves. What this does is that it provides the teacher with the ability to be vastly more effective. It doesn’t replace them – quite the opposite. It enables them to engage more efficiently.

VB: It sounds like the difficult tasks here are instrumenting this, instrumenting the classroom to measure all this.

Meyerson: Strangely enough, it’s not that bad. We’ve run prototypes of this already. If you provide information by electronic media, and you have with that a tablet that they’re working on, you’re essentially capturing all of this in real-time as they run through their exercises or work independently. You can get it pretty quickly. It isn’t rocket science. The real rocket science part is the analytics behind it that take the data and turn it into a useful resource for the teacher.

You might, for instance, norm the behavior of a child. You know exactly how long it takes to complete certain types of exercises. You know all the information you would want to know about that child as far as how they perform. Then what happens is, if you see performance falling far below the norm all of a sudden, it alerts you that there may be a problem at home. Maybe they’re not getting adequate sleep. Maybe the bus transportation is fouled up. Who knows? But the ability to capture data of all types – not just educational, but just data that impacts the health and well-being of a child – all of that is possible. It’s quite powerful.

The key is, it’s all private. This is held encrypted in a persona within the system. You can secure it to an astonishing level, should you choose to do so.

VB: I guess this is already visible, because you have this experiment going with the Gwinnett County schools.

Meyerson: We have a number of schools we’re working with. We gain this data from their feedback. It enables you to learn what’s working and what’s not working in a rush.

The key thing is, you don’t want to waste two years of somebody’s education because somebody has some scheme about how to teach math better, and it turns out they’re just wrong. That can be a big problem.

VB: Moving on to the next one, my first reaction to that was, poor Amazon.com. Do you think buying local is really going to beat e-commerce?

Meyerson: A vast number of people, if they had the option of going locally and having access to that kind of ease of use–You walk into a store and you’re basically using an app that they’ve supplied. Say you have a particular interest in SLR cameras. You’ve been looking online at both full-size ones and some of the new smaller versions. You’re not sure if your hands are too big to accommodate it. Imagine the ability to walk to a local shop and have it know that you’re interested in these things, and without having to track somebody down, it says, “Would you like me to show you this particular camera? Would you like someone to meet you in Aisle 3, Section 2?”

The ability to do something painlessly, to have the hands-on experience without the hassle of trying to find help and locate the item, that’s very powerful. Similarly, when you go into a store—For instance, the neighborhood store where you get your groceries. If that store has the ability to know your preferences, it might say as you walk in, “You haven’t bought your favorite non-wheat-based bread in two weeks. I know you buy that every two weeks. You might be running low. The spelt bread is on Aisle 2.”

Making that personal set of information available to you instantly and easily, it’s very interesting. You’re not talking about two-day delivery. Not to mention, it’s very green, because you’re not dragging something halfway across the country, only to ship it all the way back the next day because it doesn’t fit. There’s a lot to be said for that. Looking at certain classes of purchases, where people want to get their hands on it, the trick is to make it as easy as it would be online. That means it’s instantly in your hands. It’s delivered immediately. You don’t have to hike around looking for it.

Right now, the experience at a typical big-box store doesn’t resemble what I’ve described. But it will get there.

VB: It almost sounds like a return to Webvan there. I don’t know if you guys have thought about that. Also, is there any additional privacy concern on this front, buying local as opposed to buying on Amazon?

Meyerson: That’s the question. How private are you at Amazon? They know all your preferences. They have a record of everything you’ve done. They have virtually all your personal information.

VB: The thing I don’t necessarily want everybody to know—Say I have 10 bottles of wine in my refrigerator.

Meyerson: That’s a good point. This is actually done electronically, not necessarily with human intervention. It’s certainly more private than going to the store and just loading up a bucket with 10 bottles. The difference here is, it can be delivered in what amounts to a box. You pick it up and walk out the store and no person has a clue what you did.

Whether it’s online or in the store, it’s all handled electronically. You’re no more or less exposed. It’s just that in one case, you have your 10 bottles, which you want to take home with 10 straws and have a good evening.

VB: What’s interesting is that this area has always been about physical retail against online. It almost seems like you’re combining the two in some way.

Meyerson: Exactly. Because of the change in technology and the availability of cloud, where you can run this stuff remotely on somebody else’s nickel, we turn it into pure op-ex, as opposed to a massive cap-ex investment. Even little mom-and-pop stores can offer the same services.

You’re combining the best of both worlds. On the one hand, you have a very personal relationship, which some people do prefer. At the same time, the technology they have available to serve you is as good as anything that’s been available in online shops. It’s an interesting evolution, and it is coming. A large number of things, you do want to get your hands on them and see them in person before you buy them. As you probably have heard, there are a number of online shops that have talked about setting up brick-and-mortar showrooms, for this precise reason.

VB: Next up, doctors and DNA.

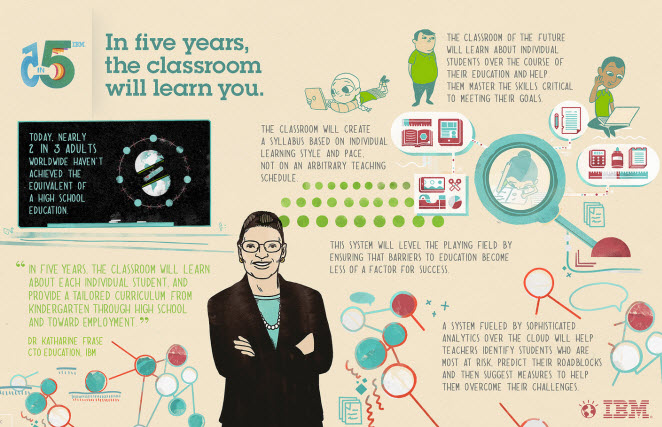

Meyerson: We put these down before all the recent announcements you’ve seen about the guys who are using DNA and other markers to re-engineer white cells and go after blood cancers. It’s quite striking. If you have enough horsepower, you can collect a vast amount of information about various diseases, various cancers and such, and you can start aligning them with the DNA knowledge that we gain from the ability to sequence people’s DNA in a reasonably short time and at a reasonably low cost.

Once you’re doing that, think about the tailored effects, as opposed to the nuclear option of chemotherapy. The whole point is, DNA indicators will let you target particular results, target particular cocktails or any other chemical treatment in a way that minimizes damage to innocent tissue and maximizes damage where you want it. If you can get something that is absolutely chemically specific to the surface of a cancer cell, you then eliminate the side effects that would be associated with applying what amounts to a poison to the body.

Targeted therapies based on DNA understanding, and the ability to correlate the DNA attributes of a given person against the results of a particular treatment protocol, that is a huge protocol. It’s starting. The reason it’s 5 in 5 is because we’re just now beginning to hear some astonishing results. In five years, it won’t be unusual.

VB: The other thing that made some news was 23andMe and the FDA. The FDA was concerned about inaccurate DNA reports that might cause you to make the wrong decision, and that there was no oversight of this. That caused 23andMe to retreat a bit and say, “Okay, we’ll wait on that and do our ancestry research in the meantime.” How much of that is going to maybe interrupt this process here?

Meyerson: I have no idea what 23andMe did by way of background research or anything else. But I don’t think it’ll have any impact here. There were always going to be early movers taking risks. There was always going to be the issue of folks who don’t have enough data yet. But the key point is, data is being gathered on a global scale.

As you get these enormous data warehouses, you can see the alignment between these particular markers within the DNA and a clinical result based on some protocol, and you start lining up all the cases. If you have this particular DNA market, you’re also subject to this disease. Here’s the protocol that’s most likely, in prior times, beaten that disease. Just that information alone – the ability to target a treatment – is monumental.

Today, they just have a book of best practices that they apply uniformly, because there is no use of DNA on a broad scale to aim treatments. There are targeted cases. The difference is, this will become pervasive in the next five years. You’ll reach a point where one of the first steps, if you have a serious disease, will be to take a look at your DNA and see if one of the magic bullets that have been identified over the course of several years applies to your case.

That’s what they’re finding, by the way. They’re finding magic bullets, as we’ve seen in the recent oncology results. It’s stunning. These are people who were on what would amount to their last leg, and they’ve ended up thriving because they had the right knowledge of how to treat that particular problem, based on a very specific characteristic found in their DNA.

VB: The question that comes up, if we get too good at treating these diseases, do we have an overpopulation problem? Has some thought gone into that issue as well?

Meyerson: There are a lot of very benign ways of controlling population that don’t involve killing people. [laughter] I’ll stop there, because that’s an easy one. I’m not sure anyone’s planning on population control through any more draconian effort than what people practice today.

VB: Number four, “a digital guardian to protect you.”

Meyerson: That’s pretty funky. Something on the order of 12 million people a year in the U.S. get their identities stolen. It’s ridiculous. The thing is, unfortunately, a lot of folks – because you have to be pretty tech-savvy – don’t know what to do when they get a URL in their e-mail that says it’s their bank and there’s a problem with their account. Next thing they know, a site comes up that looks a lot like their bank, and it asks for their password and ID and they figure they’re logging on. What they’ve just done is given some hacker all the information they need to empty their account. And the reason is that they don’t know what that URL really means.

That’s the sad truth of the web. Thieves take advantage of the fact that most people are inherently good and trusting. But you shouldn’t have to become a cynic. What should happen is that there should be really robust ways of protecting people. You have people using all kinds of digital means to rip folks off. Why don’t we use digital means to protect them?

The fascinating thing that’s happening now is that we’ve figured out that most malware and viruses and can be contained with the use of good software. Various companies sell that. The problem is that now the bad guys have figured that out, so they resort to techniques that lie outside of what those kinds of protections can discover. They don’t write a virus that makes you system do something bad. Instead, they’ll send a phishing e-mail or a bad URL. You can’t look for the signature of an attack in that.

In the old days you’d look for the signature code of a virus and presto, you killed the virus. Nowadays you have to figure out ways to look at the behavior of systems. With processors becoming more powerful over the last couple years – and they’re now found in handheld devices, from Samsung or Apple or whoever else – those processors have enough horsepower to do some very clever things. You look at the behavior of the device you have, all the connections it’s making, and you spot anomalous behavior.

You’re not looking for a particular piece of code. This machine protecting you looks in detail at your normative behavior, and it starts screaming when it sees something out of the norm. When it sees you clicking on a website where the image name of what you click on is not the same as what you arrive, it screams at you, “Stop, this is bogus!” Or when you read a phishing e-mail, it reads it with you and says, “Uh, are you really sure you want to do this?”

It’s not something where a third-party is getting your information and doing this for you. This is your agent – again, your persona writ large, because of the tremendous compute horsepower available these days. It’s a bit like having Jiminy Cricket on your shoulder, armed with a bat with a spike in it.

VB: “Guardian” suggests something you trust. If you can’t trust yourself, you can trust somebody who’s better at this stuff.

Meyerson: What you’re doing is trusting a digital persona. This is a smart learning system. It learns your behaviors over time, takes that learning, and notices when you’re doing something abnormal. That makes it a powerful weapon against the bad guys. The bad guys have an awful day when you can instantly recognize that they are the bad guys. You recognize them for what they are and shut them down before they get into your account.

VB: The smarter bad guys seem like the ones that would take a dollar off your credit card every month, instead of the ones who empty your bank account.

Meyerson: That’s true. There are guys who do that. The catch is, if they’re doing that, it doesn’t fall within the norm either. If they take a dollar out and it says it’s going to some business name, this guardian has nothing better to do than look at everything you do – everything – and look into where that dollar’s going. It’ll track it back to where it arrived and say, “Does this make sense, that it’s going to God knows where? I don’t think so.”

The point I’m making is, again, it’s not a normal behavior. You’re right that they can do this, because as a person you wouldn’t recognize it. But this machine will spot it because it traces it to its destination, and if it says it’s doing X for you, the machine will find out what X is. X, of course, won’t check out. It won’t correspond to anything you’ve otherwise interacted with. This thing will be a detective and you don’t have to do anything.

The other thing that happens, by the way – and we have systems like this already – IBM has a smart system called QRadar. It looks at every connection being made to everything from a given set of IP addresses. It can spot behaviors in the thing you connect to that are already suspect and set off an alarm. But it’s not just an alarm that goes to you. It goes to everyone going to that address. Once you know that’s a bad address, it instantly tells the planet, “Hey, look out for this.”

The reason bad guys get away with what they do, even if I can spot a scam email, the sad part is, there will be someone who just might not be paying attention. But any time somebody flags one of these things as bogus, because these entities talk to one another, they collaborate and say, “Put a check on this.” You don’t have to go look on some list of scam emails. It will be your guardian. Its job will be to scan the web and scan sites that identify these kinds of phishing expeditions and know in advance if you’re being targeted.

VB: For number five, the smart cities, the thing that came to mind was—I wonder what you thought about this video game called Watch Dogs. The premise is that cities have become smart, and then a hacker hacks into them and controls the city. He uses the ability to find out about everybody for his own sort of nefarious ends. At the same time, he’s fighting against some kind of NSA-like organization. It’s a very big game coming from Ubisoft in 2014. It’ll raise the awareness of smart cities in that respect. It’s all about what goes wrong in a smart city.

Meyerson: I hadn’t heard of that. But here’s the deal. Given that there’s a trillion dollars moving around on the web through online shopping—You’re already there, in so many aspects of your life. The diversity of the city is such that you’re already there. I’d much rather have the city linked and be one integrated entity. The reason being, then I can protect it.

You already have your electronic controls in power plants. You have the pumps that move sewage for cities like New Orleans, below sea level. I’d much rather have them fully integrated, where I can maintain watch over them and do the same thing. You have an agent that watches the city — no different from the agent that watches you, but it’s vastly more powerful.

Again, it looks for the normative behavior. Some wise guy decides they’ll make the sewage pumps run backwards and make a mess. You’ll instantly pick up on that because it’s not the normal behavior. It instantly shuts down. We’re already in this mode. You can’t change the past. I would argue the best thing you could possibly do is integrate all of this and make sure you’re looking at everything.

VB: That one might seem a little far-fetched. But the fact that hackers exist, and that there’s this possibly Orwellian aspect to it—It could make people feel protected, but it could also make them feel vulnerable.

Meyerson: The bottom line is that hackers are a modern-day reality. In my own view, if you look at what the smart city is about to begin with, it’s much less about the physical infrastructure. That’s there already. It’s electronic. If you go into the subway, it tells you that the train is two minutes away, now here it comes. All of that is done.

What we’re talking about way beyond that is a city that becomes fully inclusive. Right now, the feedback mechanisms are awful. If you think about it, what is it? You hate the mayor, so you vote for his successor in a couple of years, at best. This sort of thing is very difficult. There are public meetings, but maybe you work odd hours and you can’t participate in city government by going somewhere remote and sitting down for two hours of folks yelling at each other.

Imagine if you had the ability to instantaneously get feedback from the city’s population on changes you’ve made, because you have a site people can access from anywhere. Or it might not even require the site. Maybe there’s an app – you’re standing on a bus, you bring up the comment app, and now you can make your contribution on the bus. It assumes, based on your position and what you’re doing – in this case, using public transit – that you have a comment. It could be positive, negative, ambivalent. The point is, instant feedback. The ability to make a change in city government and get feedback from the population in a matter of hours or days would be terrific for driving quality of life.

You can quantify quality of life issues like you could never do before. You could ask people for permission to use the microphone in their handset, let’s say, for 30 seconds every hour. It takes the microphone, turns it on, turns on the GPS, and picks up where you are in the city for 30 seconds every hour. By mapping the city’s noise levels through that microphone – just the noise levels alone – you get a quality of life measure.

If enough people participate, you get a sonic map of the city. That alerts you problem areas, where you can set noise thresholds above which you immediately send people to investigate. Similarly, you could follow patterns, where noise is evolving to louder levels every day. Again, it’s the same question. What am I doing wrong?

You can also query people on quality of life measurements. You could say, “What do you think about the quality of life in this city?” And then you correlate that commentary against the local issues in someone’s region. You can decide, from that, where you should make your investments to get the biggest bang for the buck. You may know the noise levels in a region are high, but you also may know that transportation there is very crowded. But by looking at what people themselves value as their biggest issue and getting that accurate feedback, you can make investments with the right priority.

You don’t just have to guess. You can quantify the benefit. That’s a great value, because quality of life attracts people. People, as they move into a city, drive value into the city. The U.S. has a consumer economy. You want to build a city, bring people in. You want to bring people in, improve their quality of life.

I have this old war cry from my days as a hardcore physicist. I always have to remind people. Data wins. A vast amount of time, we make decisions without data. We have a feeling, an opinion. Maybe we’ve gone out and probed some people. But we don’t have hard data. This is a way to get hard data in a time that’s almost unimaginable at present.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More