[This is part one of a two-part story on how the casual game market is evolving. See the second part here.]

[This is part one of a two-part story on how the casual game market is evolving. See the second part here.]

A year ago, the iPhone and social games on Facebook were barely on the radar at the Casual Connect conference in Seattle. But at last week’s conference, most of the attention focused on the two fastest-growing and most exciting parts of the video game business: the iPhone platform and social games.

In little more than a year, more than 14,000 games have appeared on both the iPhone and Facebook platforms. It took many more years to get as many games on casual game web sites on the Internet.

This Cambrian explosion of games is exciting as games become the premier category on both Facebook and the iPhone. The addition of the social game companies probably explains why the conference in the Emerald City grew: there were 2,007 registrants this year, compared to 1,850 a year ago, in spite of the recession’s effect on travel. And in spite of the recession, the growth means that games are gaining on other forms of entertainment such as movies, TV and music. More than 63 percent of Americans now play games.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

“This has been one of the most transformative years in gaming,” said Anita Frazier, an analyst at market researcher NPD Group.

But the old guard of the casual games industry is finding that profits are shifting fast. They have to adapt or sink amid a sea of free games. At stake are long-term monetary relationships with hundreds of millions of customers. “The social networks are essentially coming in and stealing our customers,” said one casual game web site industry executive.

This story is our summation of the casual game industry in transition, much like our related overview story on social games coming of age.

First, some definitions

First, some definitions

Casual games are short and simple experiences that people play as a diversion. They’re not the intense and complex hardcore games played as a primary source of entertainment.

Socials games are those played with your friends. Some of them are casual, such as short and simple games on Facebook. Others are hardcore, like games played with friends on Xbox Live via the Xbox 360 game console.

For the most part, we’ll refer to social games as the casual sort played on Facebook in relatively short bursts of fun with other players. Casual games and social games are related, but they’re not the same. It is because the new social games are descended from casual games that the older casual game makers feel like the new social game makers have stolen their playbook.

Traditional casual game companies who built their businesses over years are envious of newcomers like Zynga, Playdom, Playfish, Tapulous, Ngmoco and Social Gaming Network. These Young Turks are attracting investors, users, and revenues in record time despite the recession. The social game companies are in a burst of hiring, and their speakers drew the biggest crowds at the conference.

Last year, Bart Decrem, chief executive of Tapulous, was hoping he could score a million customers in a year for his iPhone rhythm tapping game, Tap Tap Revenge. He got a million customers in 10 days and now has 15 million. In effect, the upstarts are crashing the party of the experienced casual game developers. Social games might hit a half billion in revenues this year. In 2007, before a price war began, casual games were an estimated $2.25 billion industry.

The casual game companies are chagrined in part because they got started earlier than the Young Turks in their quest to disrupt the traditional console game industry, but now they find themselves in the position of being disrupted themselves by the social game companies. Zynga, which rose to fame with a simple social poker game, now has more than 66 million monthly active users.

“I’m envious of Zynga because they make it look so easy,” said the chief executive of a casual game studio that is closing its doors.

The rise of casual games 1.0

The rise of casual games 1.0

Casual game portals — Yahoo Games, MSN Games, Big Fish Games, Real Games, Wild Tangent and others — grew their audience to tens of millions of gamers over the last decade. Thanks to addictive “match three” games like PopCap Games’ Bejeweled, which appeared on multiple sites, these portals hooked a lot of people on casual fare, meaning the games were not as time-consuming or complex as hardcore games.

The game topics were broader, less focused on violence, and gender neutral. Because they cost less to make, casual game makers could afford to be more creative and take more risks. They could be more imaginative. The casual game makers discovered they could monetize the fans of casual games with the “try before you buy” model, where you played a game for a limited period and then paid $19.99 to unlock the game for an unlimited time.

The casual games that appeared on web portal sites were disruptive to the more expensive $50 or $6o console games. But they also expanded the market to include women over 35, a category where games had barely succeeded in the past. And the majority of casual game players are now women. The expansion led to a wave of casual game companies such as PopCap, RealGames, PlayFirst, Shockwave.com, and Pogo.com (now owned by Electronic Arts).

This first wave of companies, which kicked off around 2001 or so, triggered what Tim Chang, a principal at Norwest Venture Partners, called Casual Games 1.0.

In parallel, a bunch of other companies took casual games into the mobile market. Real Networks, Glu Mobile, Digital Chocolate, and Jamdat brought thousands of games to more than 1,000 cell phones around the globe. The $5 or less games disrupted the portable game market — where gamers paid $30 for Nintendo DS or Sony PlayStation Portable titles — but they also expanded the market to non-gamers. The mobile casual game trend hits its peak in 2005, when Electronic Arts bought Jamdat for $680 million.

With expansion opportunities in web games or cell phone games, many independent game developers, unable to cope with the $10 million-plus budgets and 100-person teams of the console games, found they could thrive in the new casual world. They ran comfortable businesses, creating a game in a few months with a few people at low expenses.

They could fire and forget, meaning they could publish a game and move on to the next one. The creative autonomy tempted even John Carmack, the co-founder of id Software, who began making mobile games all by himself in his spare time. While Carmack and others relished the lower production costs and faster product cycles, the lower barriers to entry led to a flood of content on the market, with many of the same successful games syndicated across many web sites and cell phones.

The casual games hit a rut, with most games turning out to be a variation on themes such as “match three,” “hidden object,” “tower defense” or other such addictive game mechanics. It raised the question: can there be too many game makers, particularly if there isn’t an unlimited number of customers. That’s like the problem of sheep over-grazing a field and ruining it as a source of food. Or does an abundance of game developers and games lead to an expansion of the market, sort of like a field that never ends?

The recession grinds the gears of the casual business

The recession grinds the gears of the casual business

Without a huge uptick in demand or a innovation, the abundance of games can lead to a collapse of prices. In the casual games market, it looks like the flood of titles has taken its inevitable toll. When I look back at the past year and think about how many free casual games have hit the market, and how the quality of these free games is getting better and better, I’m astounded.

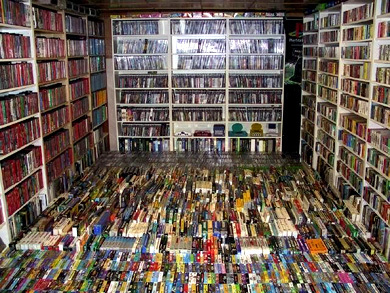

There are ways to monetize free games. Companies such as Mochi Media insert ads into casual web games built with Adobe Flash. But the ad revenues often generated hundreds of thousands of dollars for hit games, not millions, and the ad model has taken a hit in the recession. Flash games are viewed as a hobbyist market, even as their numbers have grown to more than 20,000. [photo credit: gamerchip].

The mainstay of the beefier casual games — games you can download to your own computer — also hit the wall. In the past year, the “try before you buy” model collapsed. Amazon.com introduced games at $9.99. The iPhone caught fire, with thousands of games available for free or the low price of 99 cents. Social networks Facebook and MySpace have captured the attention of hundreds of millions of web visitors, and they’re holding onto them via free or low-priced games. Many try-before-you-buy games now start at $7.

Real Networks is a case in point of how casual game publishers and portal operators have struggled with this change. The company improved its reach by syndicating its games to more than 50 different web partners, such as Comcast, in the last six months. It also grew unit sales of its games by 46 percent in the past year. But average prices fell by 20 percent to 25 percent, and its audience increased only 2 percent. Frazier, the analyst for NPD, said that overall prices for casual games have fallen 20 percent in the past year.

Real Networks has seen interest in ad-based games rise. Ad impressions are up 11 percent, and clicks on ads are up 13 percent, but ad revenue per 1,000 users is down 25 percent because of the recession. To cope with the changes, Real Networks has been on a quest to move its games everywhere, including the iPhone and consoles.

The migration to social gaming, or Casual Games 2.0, is underway

The migration to social gaming, or Casual Games 2.0, is underway

Life is easier for companies that are successfully combining gaming with social networks. This so-called Casual Games 2.0 phenomenon is creating a migration from the old guard casual to social casual games

Zynga, whose Texas HoldEm poker game on Facebook has a monthly audience of 15 million players, is expanding as if there were no recession. The company makes revenue when players purchase poker chips. It is thus cashing in on a “virtual goods” business model in transactions that have become seamless on the Facebook platform. [photo credit: paulnoll].

Zynga’s problem is that it can’t hire fast enough. The San Francisco company has dozens of open positions, even though it already has 350 employees and contractors. At Casual Connect, Zynga employees were aggressively recruiting talented developers.

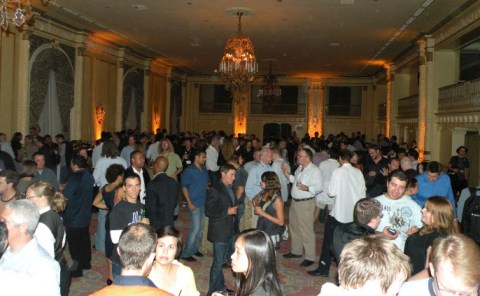

Playdom, which is the leading social game company on MySpace, has 75 employees and is expanding to 200 in the next four months, if it meets its hiring plans, said John Pleasants, chief executive of the Mountain View, Calif.-based company. Pleasants himself left the No. 2 job at Electronic Arts to join Playdom. He happily threw a party at Casual Connect that became a standing-room only affair, packed with apparent job seekers from Casual 1.0.

On the iPhone, Ngmoco has landed big fish Simon Jeffery, former president of Sega of America, as its top publishing executive. Social Gaming Network has just 30 employees, but it is doubling the size of its contractor workforce in Brazil.

For those who want to be indie developers, the options are plentiful. We’ve told the stories of iPhone hits such as Pocket God, a No. 1 hit developed by a two-man company, Bolt Creative. Chang says that there has never been a better time to be an entrepreneur to create a “lifestyle business,” where you can quit your day job and make money as an indie game developer. If a one-person shop created a 99 cent game that hit No. 1 on the AppStore, that game could generate $50,000 a day in revenues while at the No. 1 slot.

But it’s not quite so easy for a casual game development company to pull up its roots and shift into the hot sectors of social games and iPhone games. With the iPhone, for instance, there are more than 65,000 apps, including 14,000-plus games. With such numbers, it’s hard to keep pumping out the hits in a way that can sustain a large workforce.

Hence, while bigger casual game companies may lose their employees to social gaming ventures, it’s not so easy for the casual game companies to move into the same markets. Handheld Games once focused on making games for the Nintendo DS. As that market became tougher, chief executive Thomas Fessler shifted Handheld Games into making iPhone games. His team came up with clever games, such as a Zombie-shooting game that took advantage of the iPhone 3GS’ new compass. But making money has been a struggle. A single hit tennis game on the iPhone saved Fessler’s eight-person company. As 300 iPhone games appear every day, it will be interesting to see how companies such as Handheld Games will perform. Fessler was lucky that he could make the transition.

Others will not be as lucky. The process of creative destruction — where some companies shut down and other startups take their place — is always happening in the game industry. Investors are likely to favor game companies that have strategies that can deal with the big forces of the industry: the shift to social, the collapse of pricing, and a way to monetize games. This is like jumping from a tired horse to a fresh one, while the horses are still running.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More