Playing Thimbleweed Park is like discovering a lost LucasArts adventure game that’s been hidden in a closet for 25 years.

Ron Gilbert, the man who created PC classics like Maniac Mansion and The Secret of Monkey Island, is now returning to the genre with this nostalgic mystery story full of witty dialogue and point-and-click puzzles. Fans loved his old LucasArts adventure games because of their abundance of charm and cleverness, and Thimbleweed Park looks to continue that tradition. GamesBeat interviewed Gilbert last week at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco and played the game.

We talked about the difficulties of making a game designed to appeal to modern and retro fans, and he also explained his skepticism of virtual reality.

GamesBeat: I’ve always wanted to embarrass myself in front of you. I never needed a FAQ to beat your games. [Laughs]

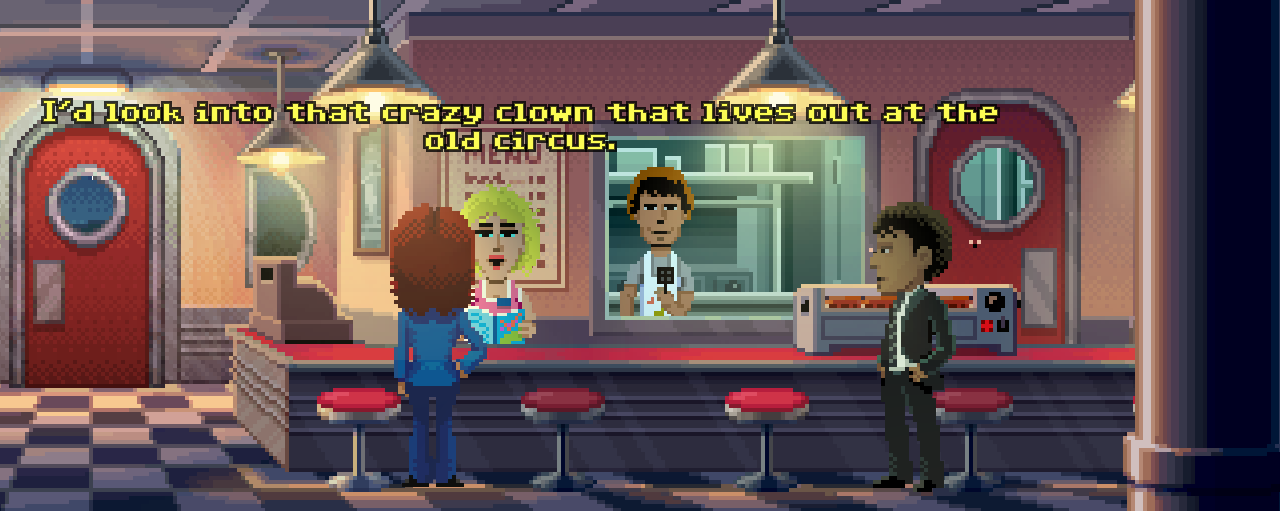

Ron Gilbert: You know about the game. I kickstarted it a year ago in December. The game is a story about these two detectives, Agent Ray and Agent Reyes, who show up in the town of Thimbleweed to investigate a dead body found under a bridge.

The body is the tip of the iceberg. The game is not a detective story where you go around gathering clues and all that stuff. The body is really an excuse to quickly move us into the real story about what’s going on in this strange little town. The body is — I think about the body as so unimportant in the game that it sits in the water the entire game. Nobody moves it. Nobody touches it. It’s almost this forgotten thing as we move on through the story.

We’ve opted to use the interface, the classic interface.

GamesBeat: I miss those verbs.

Gilbert: A lot of people do. I miss them as well. Adventure games devolved to this state where everything is “use.” It really simplified stuff a little too much for me. I wanted to bring back the verbs. Even some of the testing, the playtesting we’ve done with people who are not real adventure game fans, they kind of like this interface. It’s very clear to them. They want to open the door, they click open and they click the door. They want to close the door, they close the door. It’s simple.

There’s a bit of a period where they don’t quite get it, but once they get they can do that, it’s a very discoverable interface. When everything is just tapping on something or weird swipes and stuff, it’s not very discoverable. You just do a lot of floundering around until you figure out what things do. I like that old interface.

There’s definitely some streamlining. When we hover over the door the close verb is highlighted. If you right click they just do that now. Open is highlighted. There’s a lot of streamlining we do to move you through that. But I do like that interface.

GamesBeat: And there’s no LucasArts hotline these days.

Gilbert: People back then liked really obscure puzzles. A lot of players today who aren’t used to playing this stuff, they do like the puzzles to make more sense. They can still be hard puzzles, they’re just not obscure ridiculous puzzles.

GamesBeat: In those days, you would have one game for a few months, so it was fun to go around and click everything.

Gilbert: Yeah. There are so many games to buy these days. The game will have two modes, a standard mode and a hard mode. If you’re the kind of person who just wants to explore the world and see the story, but not have to spend days doing something, you can just play the standard mode. If you like a lot of hard puzzles you play in hard mode and get the full experience.

GamesBeat: Very cool.

Gilbert: A lot of modern adventure game players — they want reassurance that they’re doing the right thing. They don’t want to be led around. They don’t want to be forced to do this stuff. But they want reassurance that they’re on the right path. And so that’s the kind of thing we’re trying to do with the game, to build that stuff into the game to open this thing up to a broader audience than just the fans of the genre.

GamesBeat: It’s more playable without having to be an episodic game.

Gilbert: Episodic adventure games are nice, because they’re smaller things, but to me adventure games are about slowly opening up these vast worlds. Episodic stuff has always felt a little too linear to me, compared to having this gigantic world I can eventually explore.

GamesBeat: It seems to be a trend, like in what Telltale is doing, where adventure games are more narrative-focused than puzzle-focused these days.

Gilbert: Yeah. You can have a nice blend of those things. Some adventure games do become all about puzzles. If you can blend that stuff where there is a nice narrative focus and you really do feel like there’s a story that you’re uncovering and moving through and affecting with the types of things you do, I think that’s good. But puzzles kind of move the story forward in my mind.

GamesBeat: You’ve kind of dabbled with returning to the adventure genre in stuff like The Cave. Why did you now fully jump in with this super retro kind of callback?

Gilbert: A lot of it is looking back at some of those old games and feeling like there was a charm to them. Although modern adventure games are very good and I enjoy a lot of stuff like Firewatch and the Telltale stuff — that stuff’s very good. But there’s this charm that I feel is missing at some level. It’s kind of going back to this to discover what it is about those games that was so interesting.

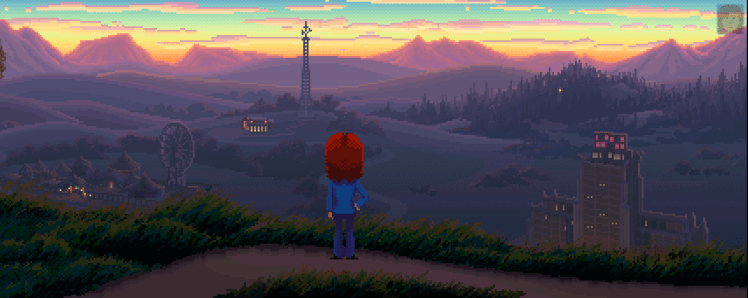

GamesBeat: Was it a challenge? This art style — the proportions are bringing to mind Maniac Mansion, but there might be a little more detail. Maybe a bit more Monkey Island. Was it hard to balance different aspects of the aesthetics from those old games?

Gilbert: We picked what we liked. I kind of like those big-headed characters that were in Maniac, because so much about a person’s personality comes from their face. Being able to have larger heads on people, you get a lot more personality in the face.

Mark Ferrari, who did all the backgrounds for Monkey Island, he did some of the backgrounds for this game. The technology has advanced. There’s a lot more we can do, all this nice parallaxing when things are moving. Mark has just grown as an artist over 30 years. He’s a lot better than he was back then. So we want to use what he does really well with his 8-bit pixel art.

GamesBeat: So much of it is a callback, but this specific story setup, this detective sort of thing — it isn’t necessarily something I immediately associate with an old-school LucasArts game. Is this an idea you’ve been mulling over for a while? Or did you decide to do another adventure game and then come up with this setup?

Gilbert: When Gary [Winnick, co-creator of Maniac Mansion and this game] and I first talked about this, we wanted to figure out how to recapture the charm of those games. Then we sat down and figured out the story. We came up with like 30 different stories. Actually, on the development blog, I published all 30 of those stories. You can see how we kind of narrowed them down and refined them. This is actually a combination of three of the stories that we molded together in this one idea.

GamesBeat: It must be nice now because you can make a retro-looking game, but you don’t have actual technical limitations. There’s a lot more colors here than you could have done in the old PC days.

Gilbert: And the parallax, being able to get that many levels of depth. That’s something we couldn’t do. We also do a lot of lighting. As the characters walk around under street lamps they light up from those. We’re doing actual light casting in the world using shaders and all that stuff to do that.

The way we think about it, we want this game to be how you remember those games, not necessarily how they actually were. In our mind we kind of project a lot of these really cool things that those old games had. Now we can do those things.

GamesBeat: Does the amount of affinity that people still have for those adventure games surprise you at all? There are a lot of PC games from that era, and some of them are remembered fondly, but it seems like LucasArts adventure games are specifically — I know I’m not the only one. People still go back and play them all the time.

Gilbert: There’s an amazing longevity to those games. It’s really interesting. Again, I don’t know that I exactly know why, but I think that’s why we made this game. Let’s try to figure out why that is. Let’s go back to the charm that those games had and see if we can figure out what it is about those games. It amazes me that people still play Monkey Island today.

GamesBeat: Do you think this is something you wouldn’t have been able to do if it weren’t for crowdfunding?

Gilbert: Yeah, I don’t think so. I might have been able to get a publisher interested in this, but — I have a feeling that working under somebody, there would have been a lot of pressure to modernize it too much. More than we really wanted to. Things like Kickstarter are great because you can really go right to the fans of the genre, fans of ourselves, and get them to fund something. We have a lot more freedom to build what we want to build.

GamesBeat: Size-wise, is this game bigger or smaller than what you worked with on something like Maniac or Secret of Monkey Island?

Gilbert: It’s much bigger than Maniac Mansion. I’d say this is about the size of Monkey Island in terms of the number of rooms and puzzles and the complexity of puzzles.

GamesBeat: Length-wise, do you think it would be on par with how long it took people to finish those older games?

Gilbert: That’s a really hard question. A lot of people look back at Monkey Island and they go, oh, that game took me 40 hours to play through! Yeah, but you were 12. It’s a little bit of a different world. I have watched people play Monkey Island today who never played that game before and they get through it in about eight hours. There’s been this weird time compression of stuff.

I’ll be happy if this is a good solid 10-hour game for people. If you play it in regular mode, maybe it’s a four-hour game? Maybe it’s a much shorter game if you’re playing it that way. But if you want the full experience you play on the hard mode.

GamesBeat: Since this is GDC 2016, I have to ask you about VR.

Gilbert: Oh, yeah. Full Oculus support, of course. [Laughs]

GamesBeat: I notice that a lot of the early virtual reality games I’m playing are basically adventure games. I call them look-and-click adventure games, since you’re aiming a cursor with your head instead of with a mouse. Do you think these titles are interesting at all?

Gilbert: I don’t know. I’m very skeptical of VR. I think VR is absolutely the future. There’s no question about that. I think that future is 20 or 30 years from now. I don’t think that future is next year. I think VR is the kind of thing that will become very, very popular when it’s embedded in our contact lenses. I don’t think it’s going to be particularly popular when we still have to strap big things on our heads.

It’s really interesting. This game — I would actually love to see this game in VR, because we have so much depth information. We have all these planes. Every object you see on the screen actually has a Z depth to it. We use that for rendering. Doing a VR version of this game, I think you’d get this wonderful sense of depth as you see all these layered — it’s 2D, but all this layered stuff going on. I wish I had more time to work with my Oculus dev kit and actually try to make that work. But I think it could be really fun to do that.

GamesBeat: Is there a launch date?

Gilbert: Either October or January. We don’t want to release in November or December or so. There’s a bunch of polish I want to do. I really want this game to be excellent when it ships. Since we don’t have a publisher lording over us, you know, if we can move it to January and it gets a lot more polished, I’d much rather do that. No later than that, though. No later than January.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More