The ISIS beheadings of journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff. The radicalization of San Bernardino shooters Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik. The Orlando nightclub massacre. Social media, encrypted messages, or online propaganda from ISIS played a role in these horrific events and countless others like them.

Yet Silicon Valley’s approach to combatting ISIS might be compared to a game of whack-a-mole at best, largely a top-down affair. Terrorists use services like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter to publish extremist propaganda and recruit followers. The tech companies, in turn, shut down the terrorists’ accounts only to have them spring up again.

But this fall, a group of five Stanford graduate students devised a promising, bottom-up approach to prevent the radicalization of Americans to ISIS. They developed their solution — called FAVE (for Friends and Families Against Violent Extremism) — using lean startup principles to identify those individuals at risk of radicalization and prevent them from joining ISIS.

The number of Americans who joined or tried to join ISIS more than doubled to about 250 in 2015, from 100 people a year earlier, according to Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Carlin. And as many as 31,500 people from across the globe have travelled to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS since 2011, although perhaps only 15,000 remain, according to recent figures. Even as ISIS continues to lose ground in Syria and Iraq, there’s the threat of bombings by so-called lone wolves or by small cells of people like last week’s Christmas Market attack in Berlin.

Hacking for diplomacy

The students behind FAVE — Anusha Balakrishnan (MS Computer Science), Hyeryung Chloe Chung (MA International Policy Studies), Gloria Chua (MS Computer Science), Jian Yang Lum (MS Statistics), and Vinaya Polamreddi (MS Computer Science) — formed a team called HackingCT, for hacking counterterrorism. It was part of a 10-week course, Hacking for Diplomacy. Led by Steve Blank of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program, and father of the Lean LaunchPad methodology, students in the course partnered with the U.S. State Department to apply lean-startup principles to global challenges.

Above: The HackingCT team.

Some students addressed human trafficking, others the refugee crisis in Europe, and still others several vexing problems. The HackingCT team was drawn to ISIS because of the large number of people it has killed. According to Chua, “In 2015 alone, there have been 11,744 attacks in 92 different countries. ISIS has also been adept in recruiting individuals to their cause. The urgency and severity of the issue is what drove us to work on this.”

Working with the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism and Countering Violent Extremism and with the Special Representative to the Muslim Communities in the Office of Religions and Global Affairs, the HackingCT team followed the three key lean startup principles: 1) sketch out a hypothesis, not a business plan; 2) talk to customers, iterate based in feedback, pivot as necessary; 3) use agile development for rapid and responsive product creation.

While the students ultimately conducted more than 100 interviews to develop FAVE, they spoke with about 20 people during the first two weeks as they attempted to understand the characteristics of those at risk for radicalization. They quickly realized that this would not help them. “It wasn’t long before we found out that there are already many in-depth and long-term research and analysis in this area,” Chua said in an email interview. “Radicalization pathways are complex and multi-causal, and there is no one single defining characteristic. It is not about poverty levels, about education levels, mental health, etc. There is just no one general trend.”

The team also looked at the usually unsuccessful efforts by various well-meaning institutions to reach at-risk individuals. Too often the messages are regarded with suspicion and lack credibility because of their overt agendas. For instance, the team examined the Global Engagement Center’s efforts of using Twitter to send messages against violent extremist groups, which received negative reactions online.

However, the group saw that “grassroots efforts like YouTube videos posted by youth that use humor to ridicule ISIS, or a local respected religious leader sharing their thoughts” could be effective, Chua said. “We identified that a message needed to be credible in the following: the message itself, the messenger, the channel, and the form.”

After several weeks, the HackingCT team had a breakthrough and, in Silicon Valley parlance, decided to pivot. “We realized our learning plateaued because we were unable to reach these at-risk individuals themselves to learn more. As in design thinking, we decided to look for analogous situations to research off of,” Chua said. “We explored gang violence, drunk driving, and suicide.”

Countering violent extremism

The team saw many similarities between suicidal ideation and online radicalization. “In both cases, the individual is in a vulnerable state, is highly susceptible to outside influence, and talking about the problem is often taboo. Also, suicide intervention and prevention is relatively new — while 20 years ago one might be hard-pressed to find any resources to intervene, today there is a wealth of resources like hotlines and more. This gave us hope that a similar transformation can happen for the CVE [for Countering Violent Extremism] space as well,” Chua said.

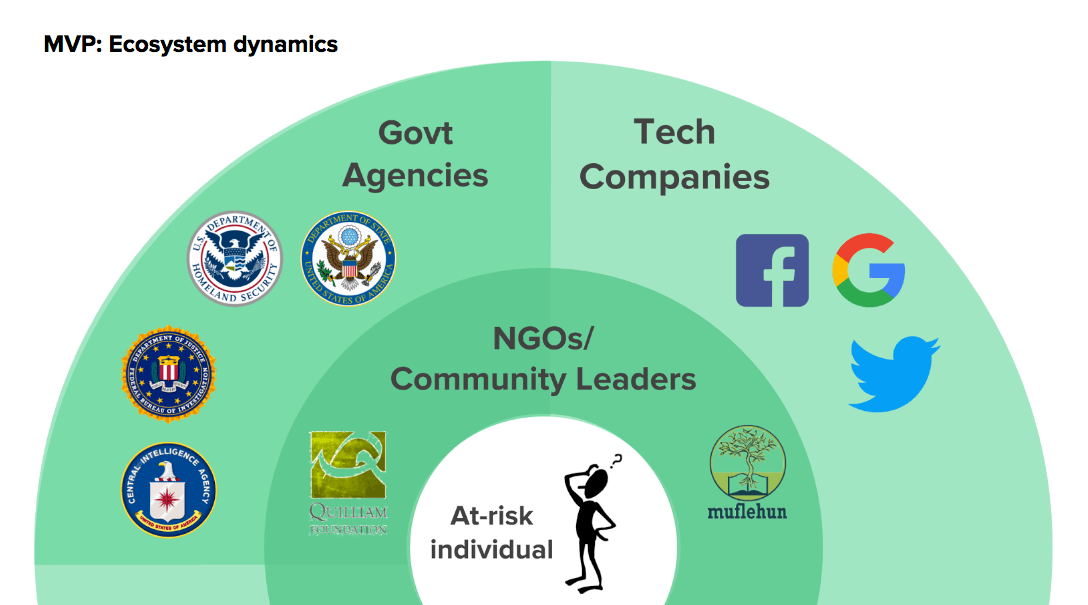

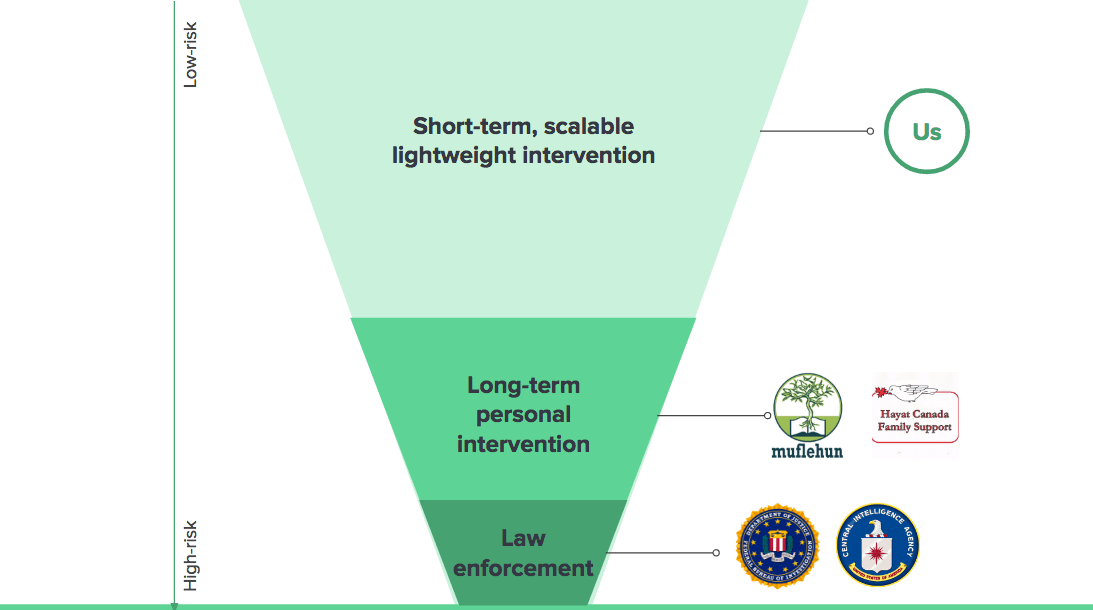

But for a person contemplating suicide, they can call 911 and get help. A person contemplating joining ISIS who calls the police is likely to be arrested. The HackingCT team determined that only family and friends can help “rescue” a person from becoming radicalized online. Trusted people could form an effective bridge between at-risk individuals and the organizations that could help them. The team also saw that 1-800 helplines could be effective, but not in the way they expected. They also looked at efforts by Google to use online ads to reach at-risk individuals.

“When we talked to NGOs, the State Department, and more, we learned that at-risk individuals were not likely to reach out and actively engage in these resources. They also pushed us to think about the people around the individual,” Chua said.

Chua explained how one of their sponsors at the State Department suggested they consider a 16-year-old who sees their friend acting differently, but then who has no idea where to go from there. She also described how an expert at one of the NGOs they spoke to showed them a presentation slide that read, “Most friends and family have an idea their family member is radicalized” but have “nowhere to turn to but the police.” The team also learned about helpline initiatives for friends and family in Austria and Canada.

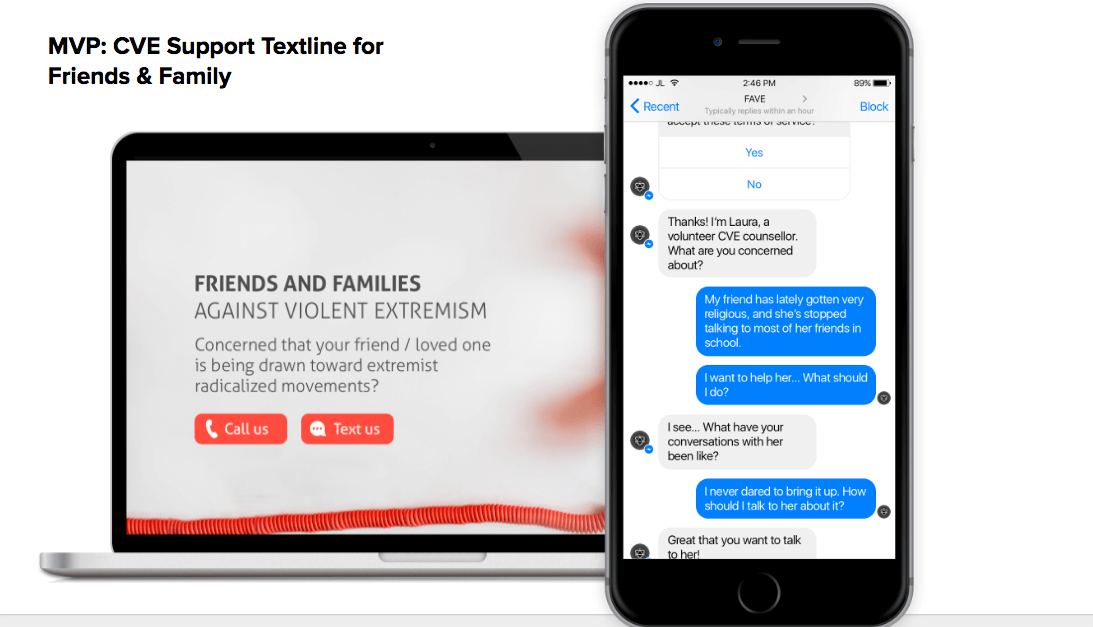

Armed with this information, in the final weeks of the course the students created a minimal viable product consisting of a helpline and textline, which resonated with the NGOs. FAVE can act as short-term, lightweight, and scalable solution that serves as a bridge to long-term, personal intervention by an NGO. It’s a solution using decades-old technology — 1-800 helplines staffed by experts — borne of a new approach — startup principles.

According to Chua, the team is discussing next steps with the State Department and seeking sponsors. They are planning FAVE pilots in one domestic and one international English-speaking city by mid-2017. Candidate cities are Minneapolis and Luton, England, two areas where individuals joined ISIS and went to Syria.

“We hope that as a team of 5 providing a fresh perspective to a growing and emerging field, we might be able to move the needle in a meaningful way,” Chua said.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More