Historically, mature private companies relied on “growth” or late-stage venture firms for their last round, or rounds, before filing for IPO. That ecosystem has been disrupted over the last few years as large public market focused investors entered the space. But just as the big money players flooded into the market, current economics are washing some of them right back out.

In 2013, IPOs returned a staggering average gain of 160% from the last private round to IPO pricing, with only 21 months between the private and public rounds. Larger public market focused funds, i.e. Fidelity, Wellington and T.Rowe had already started to cross over to invest in late-stage private rounds. Hedge funds followed to chase these returns, but with smaller balance sheets and shorter investment horizons.

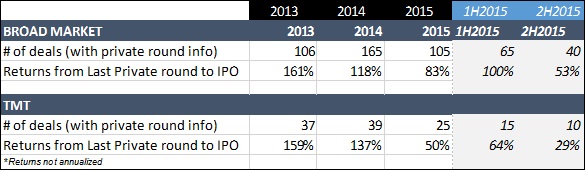

In 2015, tech, media, and telecom (TMT) IPO returns from the last private round decreased to 50%, from 137% in 2014, a 63% decline in one year. This decline intensified halfway through the year; the second half of 2015 showed a sharp 50% decrease in returns relative to the first half of the year for both TMT and the broad market.

In addition to depressed returns, the volume of IPOs decreased 36% in 2015.

How and why?

Larger rounds, driven by larger investor balance sheets, enabled companies to stay private longer. These large private companies looked a lot like public companies in size, balance sheet, and access to capital. The problem is that the “illiquidity discount” disappeared from late-stage funding rounds. Private companies were being valued relative to public companies as if they were both identically liquid instruments.

When public markets sold off in August 2015, uncertainty caused investors to become cautious and fickle, which precipitated a cooling of the IPO market. While public-equity investors can sell stocks they don’t want to own, or are forced to sell due to fund redemptions, selling private company stock is significantly harder, hence the illiquidity discount that had existed until excess demand drove it out of the market.

Crossover investors were left holding private-company stock without clarity on when, if, or at what level they could exit their positions. Public market multiple compression also decreased relative valuations, and delivered the dual detriment of longer hold times and lower returns on private investments.

This situation led to a number of valuation write-downs of private positions among crossover players. With decreasing returns, and with no liquidity options, crossover investors have pulled back from the private market, are bidding more conservatively, or are focusing elsewhere.

“We have seen the interest level in pre-IPO private financing rounds wane and valuation sensitivities increase,” John Fogelsong, Principal at Glynn Capital Management, a late-stage Sand Hill Venture Capital firm, told me a few weeks ago. “The trend started in the Spring of 2015 and intensified after the rise in global volatility over the summer.”

The future of the crossover

Late-stage investing has quickly turned into a buyer’s market, and private companies are already finding it much harder to raise capital. Rounds are taking longer to execute, and down-rounds for high-flyer “unicorns” are becoming more common. For many, this is a reality that has been a long time coming and represents a return to a rational market, where valuations must be justified at the time of financing instead of being forward-priced and expected to be grown into.

Although the spread is being materially compressed, mutual funds are still thinly profiting from investing in private rounds rather than in the open public market, for now. Also, IPO delays theoretically don’t impact their long-term view of a company. Their private company write-downs shouldn’t be considered news; they’re consistent with their public portfolio mark-to-market declines. These declines, coupled with a significant decrease in competition, allow these investors to be selective in who they fund and at what terms, particularly at what valuations.

Those chasing returns alone face a different reality. Without a long-term interest in owning a stock, returns will no longer be attractive enough to justify the risk. Many of the momentum-based cross-over investors lack the expertise to evaluate or aid the actual businesses represented by the stocks they were buying.

Mutual funds have retracted, are revising valuation methodologies, and will become much more selective buyers. Hedge funds will go away until they see another late-inning momentum opportunity, which will cause the inflation of the next cycle, although we wouldn’t expect that anytime soon. We are already seeing investors return to value over solely growth, to logical decisions, and to appropriate diligence in their investment decisions. Investors, both late-stage and venture, will still seek companies with a likely path to IPO in this new environment.

Is the crossover over? No, but its heyday is. And investors are back in the driver’s seat.

Jeremy Abelson is founder and portfolio manager at Irving Investors.

Ben Narasin was an entrepreneur for 25 years, a seed investor for 8 and is now a traditional VC as a general partner at Canvas Ventures.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More