The bubble will deflate now and then. But the air never completely goes out. Investments move in cycles, just as the industry itself does. If King’s IPO goes well, that will open to door for more IPOs and more valuation growth. If it goes badly, as it could because of the concern about one-hit wonder nature of Candy Crush Saga, the bubble will lose air. [With King’s value slipping from $7.6 billion to $5.8 billion in the first couple days of trading, we’ve lost some air].

Who is going to buy whom?

[This is the section I wrote before Facebook bought Oculus VR for $2 billion. My take on that is here]. Well, it’s no longer just the Japanese doing the buying. The other Asians and the Eastern Europeans are also going shopping.

Let’s go back to that valuation chart. You can pretty much guess that those at the top of the list are in a position to buy those at the bottom of the list.

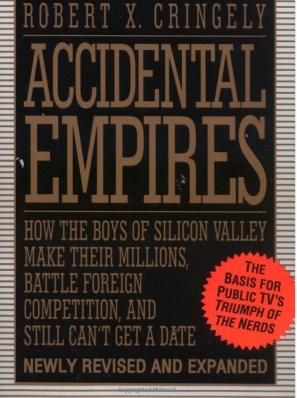

So your destiny as a game designer is to work for Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, or Disney. These are five companies that have built what I call accidental game empires, after the book by Robert X. Cringely, Accidental Empires: How the boys of Silicon Valley make their millions, battle foreign competition, and still can’t get a date. Yes, the people who hold the fate of the game industry in their hands have no experience with games and, very likely, they don’t play games.

But don’t worry. These companies have built technology platforms. And games are so insidious that they worm their way onto every platform and dominate it, much to the dismay of the clueless nongaming platform owner. As Seamus Blackley, the co-creator of the Xbox, said, “Games find a way“. It’s like life finds a way to survive. So do games, no matter how many people try to keep gaming penned up in a niche, close it off in a ghetto, or dismiss it as something for children. Games will find a way.

The benevolent view of these platform-owning benefactors of the game business is they let game publishers and developers do their thing. It’s a kind of benign neglect. That is, until a game company needs something out of them. Like, say, you want Apple to stamp out bots or fake reviews. You can ask Apple to do this, but I’m not sure they are going to listen.

You could also say that benign neglect can produce great results. Apple’s App Store generated $10 billion in revenues in 2013. The Google Play Store quadrupled its payments to developers in 2013.

Three out of four Android device owners are playing games. But before we get to excited, the average price of an Android game is six cents, according to Flurry.

These companies concentrate on making great platforms, and the game companies create their masterpieces on top of them. If you compare the results of the accidental game CEOs to the results of the game savvy CEOs, like those sitting atop Activision, Electronic Arts, and Nintendo, you can argue that the nongame CEOs are doing a better job.

Yes, the fate of the game industry is in the hands of nongamers. But even that is going to change. As you recall, the ESA says the average age of a video game player is 30. 58 percent of Americans play games. And perhaps 80 percent of young people play games. So the nongamers will die off. Ultimately, everybody will be a gamer, and the term will lose its meaning, like a movier.

And don’t forget about gamification. Those big platform companies are adopting game-like incentives in the name of growth. Gaming will find a way to take over these companies.

John Riccitiello, the former EA CEO, believes that games, and gamers, will get their revenge. The value on our chart at the top is too heavily focused on the platforms and not the content creators. He believes that, in the future, content creators will create more value. An example he brings up is Netflix, which, right or wrong, can be classified as a content company. Apple competes with Netflix in movie distribution via iTunes. But it tolerates Netflix on Apple platforms because consumers want Netflix’s content. Apple cannot push Netflix around because consumers would get upset if they could no longer access Netflix on Apple devices. Disney is another example of a very powerful content company. And nobody pushes around Mickey Mouse.

Riccitiello believes that, if our golden age of games develops as hoped, then the value created by the content companies will rise in proportion to their rightful place in entertaining consumers.

If the counterforce movement toward openness curbs the power of the platform owners, that will enable content companies to grow to their fullest. That may sound like wishful thinking, but I think this is the way that game companies could conquer the world. That is why an open ecosystem is an economic gold mine.

Do the game company valuations make sense? No.

Let’s go back to Wall Street and the Wisdom of the Crowd. Those prices are set by investors, and they have to be right, no? That’s capitalism. Supply and demand.

Another way to look at this is to view Take-Two Interactive at $2.1 billion and say that is basically the value of the Grand Theft Auto series. Try as it might, Take-Two has had a hard time convincing investors that anything else it does besides Grand Theft Auto is worth anything. So let’s call $2 billion our unit of currency, or one Grand Theft Auto.

This means that Ubisoft with Assassin’s Creed and Watch Dogs is only worth three quarters of a Grand Theft Auto. Supercell, meanwhile, is worth 1.5 Grand Theft Autos. Zynga is worth about two Grand Theft Autos. Because of Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Skylanders, Activision Blizzard is worth eight Grand Theft Autos.

Now, as you start thinking about all those Grand Theft Autos, you have to wonder: Is this valuation right? Grand Theft Auto sold more than 32.5 million units, or about $1.9 billion worth at retail.

King made $1.8 billion in revenue last year, about the same that Grand Theft Auto 5 made in revenue. But in its IPO filing, King is supposed to be valued at 3.5 Grand Theft Autos. Why? Well, King had $568 million in profits in 2013, or twice as much as Take-Two.

Now you could argue that this isn’t fair. King made Candy Crush Saga with three people. Rockstar employed hundreds over five years at a cost of around $260 million. But Rockstar made back its investment in the first 18 hours of GTA V sales.

Take-Two is basically trading at around one times current sales. Zynga is trading at four times sales. Supercell, which had $892 million in sales last year, received an investment at about three times sales. Clearly, investors don’t care about console games.

Here’s takeaway No. 1: Wall Street doesn’t understand games. By extension, investors, venture capitalists, and others don’t understand games. Certainly not the way that gamers or game developers do. And that has consequences for the game industry.

Who is going to win?

One of those consequences is arbitrage. When there are barriers in the market, inefficiencies can emerge, and somebody takes advantage of it.

A good example of this was in the late 1990s, when the French stock market soared and Infogrames was able through a combination of stock and debt to buy GT Interactive, Hasbro/Atari, and Shiny. That came to an end when Infogrames crashed in 2002. This was an example of geographic arbitrage, and we can see that the same opportunity exists today thanks to the huge growth of the valuations of the Asian companies. You could argue that they are overpaying for their acquisitions. But they are playing with inflated currency, or funny money, because of an overvalued stock market. They can afford to pay more, while other companies sit on the sidelines and gape at the high prices.

You can see the geographic arbitrage strategy emerge on a global scale now, and that is why we are using Total World Domination as the theme of our GamesBeat 2014 conference.

SoftBank is a good example. It invested in GungHo Entertainment, and it paid $1.5 billion for a 51 percent stake in Supercell. It is looking to invest in a number of companies in the West as well. That’s because it wants to build a global gaming company. If you are not thinking about building a company that can create popular games in Asia, Europe, and North America, then SoftBank may very well have you in checkmate. Global companies matter in just about every industry, with two or three winners. Why should gaming turn out any different?