Above: Sebastian Alvarado of Thwacke (left) talks about how sci-fi inspires science and vice versa.

GamesBeat: Have any predictions or propositions in the story of Watch Dogs come true?

Morin: A lot of things have happened. In the first game, we used data systems to open prison doors. A guy at DefCon demonstrated the same bug that StuxNet exploited—it could be used to simultaneously open up cells in several different prisons in the United States. Those places are fascinating, because hackers are the first ones to pick up on potential problems. Two or three years later, those problems emerge in the wider world.

We talk to hackers every day and consult with these guys. We ended up realizing how efficient they are. At the beginning of the game, you start out by backing into a stadium and creating a blackout. I think two weeks after we brainstormed that idea, there was a blackout at a football game. It became a bit uncanny, to say the least. We got accustomed to revealing stuff about Watch Dogs and seeing the same things in the headlines. There wasn’t any magic behind that. It just happened.

Edward Snowden ended up making the news I think two days before we revealed Watch Dogs at E3, which was very weird. We revealed Watch Dogs 2 in the middle of all this controversy about Trump and hacking and social media. The story we decided to pitch at E3 was about the impact of social media on democracy. It’s so in line that it feels like if we actively tried to avoid it, we’d fail.

Above: Spend Praxis points wisely on your augs in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided.

GamesBeat: Deus Ex came out of the 1990s, but you rebooted it in a way that more closely tied it to the present day and things that are currently happening.

Vu: What was interesting for us when we started Human Revolution was taking what made it a good game first. But beyond that, it was about telling a story, a human story, what it means to be human when you have these kinds of advanced technology. How does it affect people, these disruptive technologies? The internet is just one of them.

We mixed those themes with the sense of — the first Deus Ex was all about nanotechnology. That’s something you can’t really see. It was more interesting to reward players with something more noticeable. Mechanical augmentation worked for that. We went back and wrote a new story in order to give people a clearer understand of where we’re going in a few years. It was set in 2027. Today we’re almost in 2017.

And we were very interested in the work at Open Bionics. It started, actually, when they were pinged by some of our fans — “Have you seen what the Deus Ex team is talking about?” While on our side we had people who’d been inspired by the original Deus Ex to jump into scientific fields. They told us, “You should definitely talk with these guys.” We were promoting the same ideas, in some way.

GamesBeat: You had something I’d never heard of in a game before, a science advisor, Will Rosellini. He was a big fan of the game, and he came along to give a lot of explanations for how this could be real.

Vu: Absolutely. It was very funny. He’s a huge fan of the first Deus Ex games. He heard about the reboot back in the day and contacted us. I remember getting his email. “Guys, I love the game and I’ll be here in Montreal. Can we talk?” We started to discuss things with him. He says, “I’d love to help you and bring more accurate scientific detail to the game.” We jumped on the chance to work with him. We were already working with the Open Bionics conference in New York, putting that technology at the forefront, and we had some guys who’d gotten into the field because they’d played Human Revolution.

GamesBeat: And Will, while he’s been consulting with you, has also been trying to make human augmentation happen for real.

Vu: Absolutely. We believe that this isn’t just a joke or a fantasy. It’s really happening. In 2016 we’re already catching up with what we tried to create for 2027.

GamesBeat: So, science advisor to video games. That’s Sebastian’s new career. It’s interesting that we’ve come to a point where this is a job that can exist. It used to be that science fiction was so far out that you didn’t need a connection to real science. Now it’s all about things that can happen.

Alvarado: For me, my adventure went the other way around. From a very young age I was into comic books, Marvel Comics, Wolverine, things like that, and I wanted to do science so I could find the X-gene and turn it on and become a mutant. That was when I was seven or eight years old. [laughs]

Then I found myself on the career path of an academic, going to do my PhD. It was just a stroke of luck, doing my doctorate at McGill and being close to all these development studios like Ubisoft and playtesting to get free games because I was a poor graduate student. It was a unique opportunity, being in the right time and the right place, and realizing that when you do this much time doing basic research, you’re at the forefront of technology. You’re the thinker, developing the ideas that have not even gotten into textbooks yet.

When you’re in that space, you know what’s possible and what’s not. But you also know what’s speculative in terms of science. You can draw your way to a certain outcome – “If I do this experiment, I can find out the answer to that.” It’s starting to become a lot more interesting for science fiction, because we can take extra leaps forward on the notions science fiction has had for a long time and say, “Well, if we test this based on what we already know, we’re grounded in plausibility. This is a reasonable experiment to do. What if it works?” We find ourselves doing these experiments and they actually work.

I can talk about my own work. I’ve shrunk and enlarged ants. I pitched that to Marvel and got feedback from Kevin Feige off that story. Now, if I told you I could shrink and enlarge ants, you’d tell me I was a crackpot. But I published the paper. This is real science. When it made headlines, it was based on real work.

Even to this day, there are things like optogenetics. You may not hear about it, but Stanford University has Karl Deisseroth. He developed this technique that allows you to turn on individual neurons in a mouse’s brain, based on shooting different wavelengths of light at it. With a fiber optic cable or an RFID, you can shoot blue light, red light, and turn on individual groups of neurons and control behavior with it. That starts to travel into all these science fiction ideas about mind control and things like that.

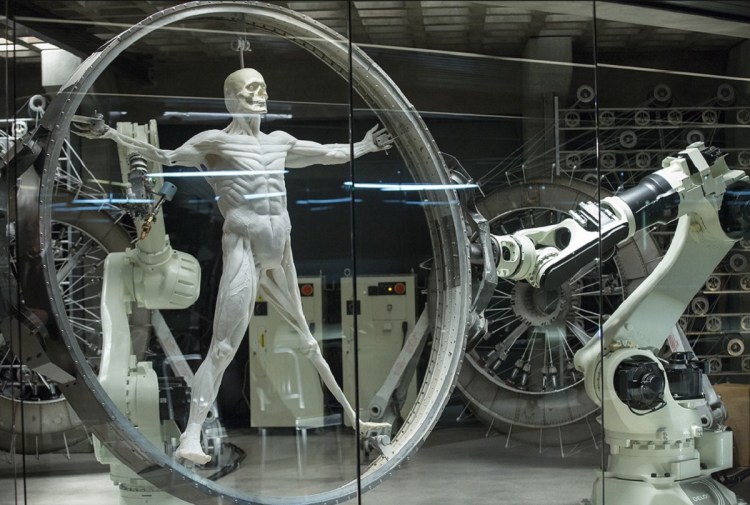

Above: Deus Ex: Mankind Divided examines the augmented future.

GamesBeat: In the CNN documentary that Deus Ex was part of, they had a lot of people with artificial limbs. It was very interesting, and very moving as well. But it also some stranger ideas, like one man who wanted to be the first wired human, connecting his brain to something. I have trouble accepting some of these.

Vu: That’s a bit of an extreme. Not everyone wants to wire their brain. But if the technology is available, someone will do it. What’s important for Deus Ex is showcasing what could happen. We’re not taking a side. It’s important for us that the player gets to choose what side they want to be on based on their own knowledge and their own background.

But yeah, we met this guy. It’s an interesting approach. It’s his way of expressing himself. Who am I to tell him it’s not right? Everyone has their own reasons. Some people have lost limbs and want to get back what they had. Some people want to extend the possibilities of what they can do. It’s not that far-fetched anymore. Oscar Pistorius, for example, the Olympic runner. We originally considered a similar story for the Deus Ex lore. What if someone on blades could run faster than anyone? Would they let him in the Olympics? Two years later it happened.

You get to a point where things are difficult to control. It’s like I said about disruptive technology. People will do what they want with it. Governments and others will try to control it, but–

GamesBeat: Because you’re working fiction, you can go places that a lot of technologists don’t. They work on their technology and try to make it happen. They don’t necessarily consider ethical implications, the consequences of how technology might go wrong. But in fiction you think about that more often.

Vu: Right. We try to see different cases, in biotech or whatever. We try to guess where things might go. We don’t take just one side. We try to offer a full spectrum of what might happen. When you brainstorm, you have a lot of intelligent people thinking around a theme. Everyone has their own experience and everyone can stretch to a certain extreme. It’s important to explore all these different possibilities, because what you might want to do with technology and what I’d do could be very different.

GamesBeat: In your game, I thought it was interesting that you’d predict people cutting their own arms off to replace it with a new one.

Vu: Well, we already have people coming up with different kinds of extensions to their own bodies. Will Rosellini has talked about people using NFC chips and so on. That’s just the start. If your limb has some defect, maybe, why not replace it with something ten times better?

Above: Open Bionics made this prosthetic arm based on Adam Jensen in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided

GamesBeat: And that leads you to your conflict between natural and augmented people, with political scapegoating happening to marginalize people. That’s the heart of what makes the story interesting.

Vu: We got to know Tilly Lockey, a woman who lost both arms. She’s now using a prototype of Adam Jensen’s arm. When people see that, instead of seeing her as diminished, everyone says it’s super cool. It’s customizable. You could do whatever you wanted with something like that. It’s not totally far-fetched to consider that someday someone’s going to say, “Hey, instead of having a new iPhone, I’ll get a new arm.”

For younger people it’s easier, maybe. It starts with tattoos and other little modifications. But you can extrapolate that to something big. It’s natural. Kids these days are more extreme, more stimulated in a lot of ways. The internet creates so much more awareness. They’ll seek extremes in everything, in ways of expressing themselves. It’s fascinating. It’s cool to explore these things in a more grand way. It shakes our way of thinking sometimes. But it’s great. I wouldn’t be surprised to see people saying, “My arm is cooler than yours. Look at the design on it.” Think of a guy who’s really good at painting figures for board games. He could end up being the best custom arm painter in the world. Why not?