GamesBeat: Watch Dogs looked at the down sides of smart cities. These are things that the companies pushing smart cities don’t talk about a lot. They say their systems are secure, but that’s what you’d expect them to say. From the research you’ve done, do you believe that this could still be a bad idea?

Morin: I’ve never thought smart cities were necessarily a bad idea by design. The thing is — just go to DefCon once, through this swarm of conferences, and you’ll realize what’s going on. Every time you’re sitting in a room at DefCon, they’ll start demonstrating whatever they want to do. Always, every single conversation, there’s this moment where they go — I remember one where a guy demonstrated how a certain system for traffic lights could be hacked. I was interested in that because we were exploring the same idea for the game. He had his backpack and his laptop, he’s pointing at an intersection in I forget which U.S. city, and suddenly he’s connected to every traffic light and controlling them. With his laptop.

Right there he called up the company that made the sensor for these traffic signals. “Hey, your product says it’s encrypted, but it’s not.” Everyone in the room starts laughing. It’s a running joke with these guys. Companies always say, “Sure, it’s encrypted,” and 99 percent of the time it’s either poorly done or not done at all. In this case it wasn’t encrypted at all. Open to connections.

So the guy on the other end says, “No, it’s encrypted,” arguing on the phone. Then he calls again and gets one level up in management, again and again. Eventually he gets a response. “Yeah, we did focus groups, and the connection was too slow with the encryption. It was a better product without it.” You focus-grouped security? And they kept claiming it was encrypted anyway. Of course the people in the cities that bought the product didn’t test it enough to notice. They just installed it. And that’s why DefCon exists. People go there and show off these things and they all find it really funny.

The thing about smart cities is, how can you secure something that isn’t just one product? A smart city isn’t a product. A smart city is an OS, an infrastructure of computers. You look back at the DDoS attack a couple of weeks ago, it’s a similar problem. All these things are connected to the internet. If one of those things is flawed — and all of them are different products from different companies, some of them that aren’t that great – the whole thing is flawed. Someone can get into the entire infrastructure and control the entire thing.

I feel like every time we create a game or a story or a universe, we want it to be relatable. A good way to make it relatable is to make people think about their own lives.

Above: The original Watch Dogs of 2014.

GamesBeat: All these things that are hackable, that’s the grain of truth in Watch Dogs. The part where it turns to fiction, maybe, is how seamlessly everything is connected and how quickly you can do a hack.

Morin: Yeah, the fiction is in how easy it is to connect to everything. But seamlessly connecting to everything, that’s closer and closer to reality. We’re making an extrapolation to a couple of years off. But often our initial conceptions end up being 80 percent reality once we ship. The speed at which this is all going is crazy. There are stories of products where, if you start extrapolating, people get scared.

GamesBeat: About six billion things are connected to the internet?

Morin: Right. And that’s growing fast. People don’t understand. They buy a camera to keep an eye on their kids — cool, right? I’ve been with my friends when they’re watching their kids on their phone with the camera while they’re on a trip. Me, I just think, there have been tons of hacks with those things. Personally it doesn’t make me feel safe. And that’s just one product. Maybe the flaw isn’t there. Maybe it’s your router. Everything that’s on the internet is connected, and most of the time they don’t sell you that part of the story.

GamesBeat: Going up a little, what do you achieve when you make a story more believable in relation to the real world?

Morin: You help people realize something new. When you create a story or an experience, like I was saying, you want to give something back, some kind of meaning. You want to say something. Sometimes you want to explore a subject and help people think about that subject. I’m more in that category. I’m interested in getting people to think about something that they don’t often think about if someone doesn’t put it in front of them.

Watch Dogs is about that. It’s about helping someone explore the repercussions of what’s going right now with the way we live. It doesn’t have to be too creepy. It can be fun, the way your character uses these things. But at the same time, you can be curious. You can mess around with these systems. It brings you to a realization. You can think about your behavior, what you do with these tools, or the bigger picture around that. Both questions are interesting. As long as people can connect with your experience in a way that’s personal to them—having relatable elements, tangible connections to real life, is a great way to go.

Vu: In Deus Ex, that’s also true for us. We can talk about mature themes. Too often people take video games very lightly. Obviously we’re making a piece of entertainment, but if we can make people think at the same time, if we can inspire people to pursue scientific fields, or even just get to know a little more about the world, that’s something we want to do. If our games can help people be more curious, that’s something we’d like to do.

Above: You still have lots of stealth options in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided.

GamesBeat: It’s said that art is a mirror.

Morin: Right, but we can also get people more engaged. The first time my kid saw Watch Dogs, they didn’t care about anything except one element. “That guy has a phone as a weapon. That’s cool.” Most 35-year-olds wouldn’t say that. But for my kid, it was like his iPod. This guy in the game is doing cool stuff with something just like it. It was relatable. I think that’s fascinating.

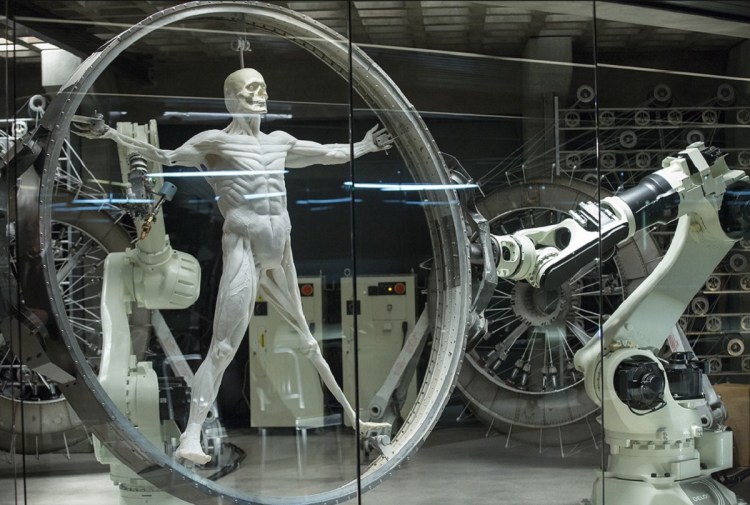

Vu: Talking about augmentation and prosthetic limbs, when we first started doing Deus Ex 10 years ago, people saw some hope in it. People who’ve lost their limbs for whatever reason feel limited. It’s not as if they’re second-class citizens, but they find themselves in a different place in society. I remember people writing to us saying things like, “I’m handicapped after a car accident. Playing your game, I felt like what I was seeing could happen for me someday.”

With Mankind Divided, it goes even further. This stuff exists. It’s not a gimmick anymore. It could be very cheap pretty soon. You can spend up to $200,000 on a prosthetic right now, but what was interesting about working with Open Bionics was that these guys wanted to make it accessible to the masses. That’s what we wanted to associate ourselves with – exposing this technology to everyone, helping people progress. If we can help make some improvement in the world, it gives what we’re doing greater meaning.

GamesBeat: That’s how augmentation gets into the world. But the interesting thing about your story is that you also reflect this consequence. What happens if somebody doesn’t have good intentions around their use of this technology and the way it divides people? It starts to feel more relevant at the end of 2016, with the scapegoating of Muslims and other people during the presidential campaign. Looking at how a consequence plays out in the story, you can imagine how it could play out in real life.

Vu: It’s everyone’s decision to see what could be the future at some point. Obviously, we didn’t take inspiration from this year in politics. We were thinking about this many years before. We’ve been inspired by the real world, though. We try to look at that and amplify it somehow. We did our homework.

Alvarado: A lot of social problems that come up don’t necessarily have much to do with technology. They’re human problems. As a scientist, I feel I have a personal responsibility to advance our knowledge as far as it can go, whether it’s used for good or ill. That’s the human decision. It’s beyond my grasp.

Video games are a great place to do this because it’s an intersection of culture and art and science. It’s whatever you make it up to be. As long as you’re able to tell your story, that’s fantastic. But it’s sometimes disturbing to look back and see how something could have happened in a negative way, and then see it happen in the same way. But again, human problems. We’re responsible for pushing ourselves, humankind, forward. What we do with the results of that is what we choose to do.

Above: A prosthetic arm based on the Deus Ex universe from Open Bionics, Razer, and Eidos Montreal.

GamesBeat: Looking back in history, you see these meetings between fiction and reality. At the height of McCarthyism, High Noon came out, where the hero is someone who stands up and is abandoned by all his friends. You had the parallel to people in Hollywood who were blacklisted. Arthur Miller wrote The Crucible around the same time about the Salem witch hunts, as a commentary on his own time. I feel like there’s an interesting place right now, where there’s all this research going into artificial intelligence. Silicon Valley is driving as hard as it can to make that happen. There’s a thousand startups in A.I. right now. People are working on self-driving cars. But fiction has proposed that there’s a consequence that comes when you get to the point of perfect A.I.

Vu: Like Sebastian was saying, it’s not about technology by itself. It’s how human beings use it. That complicates things.

GamesBeat: When I talked to SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, I asked him this question. Elon Musk has proposed that A.I. could be very bad idea. He wants people not to do it. Son’s response was that, “Well, somebody is going to do it.”

Morin: It’s hard to foresee what might happen. One way we’ve been able to deal with these things, though, is by exposing it and exploring it and talking about it. That’s what we’re trying to do. Making an advancement that can change society in a vacuum, flipping the switch without warning, is the worst thing you can do. If you have fiction talking about it, if you have games talking to a certain demographic that’s maybe different from the movies, if you have all these things exploring the subject it creates a conversation. That conversation helps society prepare, slowly but surely.

What’s hard to imagine now is the speed at which innovation, society-changing innovation, is going. It’s exponential. In the past, it took a whole world war to come up with a few advances that changed society. Now we could have far more in a year of peacetime. As long as it’s exposed to people and we generate debate, that will help. I just see a risk in the fact that maybe we won’t have time to go that far with the next couple of innovations. We’ll have to just trust in how that’s going to go. There’s no point in no longer pushing ourselves because we’re scared of the result.

Alvarado: The science fiction stories we tell in video games are incredibly important because science fiction has always been a vehicle for exploring social issues. Gender equality, racism, addiction, things that have been very hard to talk about in western cultures for a very long time. If you take somebody to a different planet or a different time and you introduce them to this shiny environment that might be real in the distant future, that lets their guard down a little. You open people up to ideas that they might otherwise instantly reject. You can slowly introduce these things.

I think about Ursula K. le Guin with The Left Hand of Darkness and what that has to say about gender. Being able to open up and unfold this idea about how we see male and female gender assignments—at first you feel like you’re just reading this space novella and you’re wondering what happens next. And then maybe it happens while you’re reading, or maybe it happens years down the road, but there are ideas there that you’ve opened your mind to, and you would have never done that otherwise.

GamesBeat: George Orwell published 1984 in 1949, and it feels like we might finally be in his totalitarian times.

Morin: It’s kind of a combination. The way I see it, it feels like we’re using Huxley’s model to sell Orwell’s reality. It’s an unexpected outcome. We’re individually in love with our little computers in our pockets and we willingly give information so that eventually we get Orwell’s reality. I don’t think it could happen. But they were both right, interestingly, in different places.

Above: Watch Dogs 2 is about corporate control of the smart city.

GamesBeat: The interesting thing about Watch Dogs 2 is that you identify the counter-force here, which is hacktivism. Hackers with a conscience and an agenda to push back when they realize that there’s a threat. It’s plausible that people like these could have social followings, could round up a lot of computing power, and become very powerful against the things they think are invasive.

Morin: It’s the model of a group of hackers. It started with kids doing for it kicks, playing mean jokes on the internet. And then suddenly they realize they can do more sophisticated stunts on more important matters. That’s why they make news and find followers. That’s pretty much how it happens in real life.