By watching you, Tobii can improve your gaming experience.

The eye-tracking technology has been honed over the past decade to a point where it is now a viable method for controlling games. Building from experience in the marketing and user-experience fields and later in assistive technology, the Stockholm-based company has created a focused platform that will let it move into the game space, giving the company an avenue into PC gaming — a market that research firm Newzoo expects to hit $30.7 billion by 2017.

The company is off to a great start. The 2015 International CES marked its debut in gaming, kicking off with a partnership with peripheral maker SteelSeries for the release of the first consumer eye tracker, the $200 SteelSeries Sentry. And while the device has some level of support for most PC games, Tobii recently announced official support for Assassin’s Creed: Rogue in cooperation with Ubisoft Kiev, making it the first to embrace the technology.

Tobii showcased its technology at the 2015 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco last week, showing both the Sentry and its dev-focused cousin, the Tobii EyeX. GamesBeat met with products and marketing vice president Henrik Johansson there to see first-hand how eye-tracking can improve gaming control.

The technology

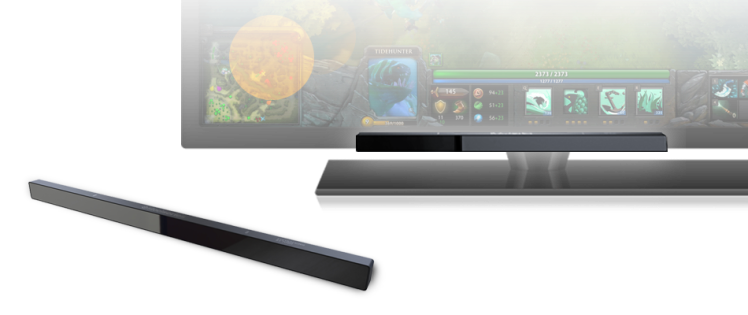

The eye-tracking device is a small, thin bar that’s similar to Sony’s PS4 PlayStation Camera in shape, though it’s strictly an infrared affair, connected to a computer via a USB3 cable. It’s light enough that a thin peel-and-stick magnet placed on the bottom ridge of a notebook screen or monitor can hold it up. Aside from a one-time calibration that has the user looking at a grid of dots, no other setup is required.

The eye-tracker’s three illuminators beam out IR light to the user’s face while the bar’s camera takes pictures of the lit face at a rate of 60 hertz. Johansson explains that the camera finds your face and eyes, and from there it can lock into where the pupils are. It tracks the pupils specifically — what they’re looking at becomes the target.

How it works

Ubisoft put the tracking tech to a different use in Assassin’s Creed: Rogue in what they call an “infinite screen” capability. While playing, it only took me a few seconds to get used to moving Rogue’s camera with my eyes, not the right thumb stick or mouse. Scanning the horizon felt just as natural as looking, though the game camera moved slower than my eyes did. Looking toward the edge of the screen had it panning that direction, allowing the field of vision to move anywhere — no mouse required.

This capability to guide the camera with my eyes tied nicely to character movement. By holding forward and simply looking toward where I wanted the character to move, it followed. If my eyes caught on a point of interest, the character would naturally move toward it. And if at any time finer control was needed, either the mouse or controller stick was always available.

Johansson explained why three controllers running in parallel worked so well in the demo.

“When you move, instead of listening to the mouse, [the game] listens to the tracker instead, he explained. “This is nicely integrated in Assassin’s Creed because it has a very intelligent engine and it actually prioritizes the different controls. In this case, the key map is first, controller is second, and eye-tracking third. Using eye tracking doesn’t take anything away.”

Substituting eye-tracking for mouse movement means that the device is already compatible with just about any PC game. Johansson says that there’s not too much work involved in deeper implementation.

“For Assassin’s Creed, it took them two to three days to implement it in. And then it took about two weeks of tweaking and fine tuning,” he said. “There are some considerations, but nothing too heavy.”

Another game, PC adventure Son of Nor, uses eye-tracking in a way that made me feel like I have a superpower. Normally, in third-person games, players would need to move a character to an object, face it, and then press a button to pick it up. Son of Nor separates character movement and object interaction, with the latter tied to eye tracking.

This let me look at large boulders and click a mouse button to pick it up, and then look at a target and click again to throw it. Doing so while moving (with keyboard control) was no problem. I found that the tracking was so quick and accurate that I could throw a boulder and actually target it mid throw to grab it again. While it wasn’t the point of Son of Nor, this mechanic was so fun and worked so well that I could see it being used as the core of another title.