There are two kinds of people in the game industry. Those who think that the industry is in fantastic shape and has entered a Golden Age where the sky is the limit. And those who think it is broken, a creative morass where very little new gets created each year.

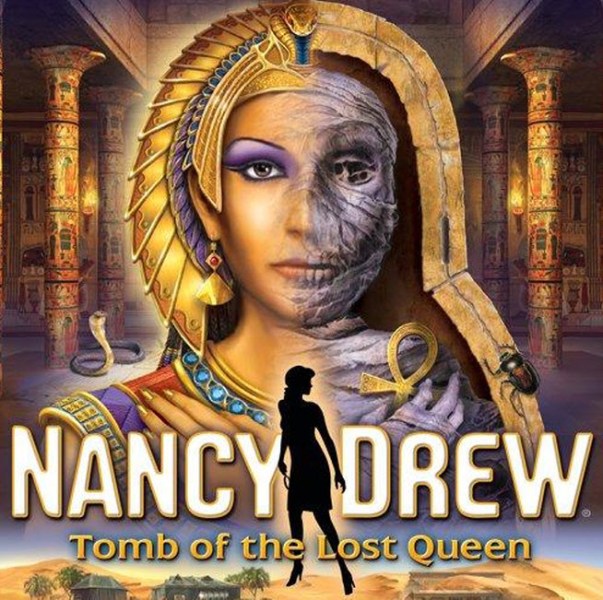

Megan Gaiser, the founder of Contagious Creativity and former CEO of Her Interactive (the maker of the Nancy Drew games for girls), believes that the game industry has a lot of potential but has a long way to go before it taps the full talents of the diverse people who work within it.

Daniel Bernstein is the former head of Sandlot Games and a current vice president at software sell-side merger and acquisition advisory firm Corum Group. He also believes that the game industry has to change to position itself for future growth, broader audiences, and more diverse talent.

They’ve come to the same conclusion that improving creative leadership at game companies will lead to naturally better products and more diverse teams. And that will make the game industry both more inclusive and more profitable at the same time, but only if we get over the traps that have held the industry back in the past.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

I interviewed Gaiser and Bernstein at the IGDA Leadership Summit in Seattle about using creative leadership to make meaning and money. They’re also going to be speakers at our upcoming GamesBeat 2015 conference on the subject of creativity and diversity. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

GamesBeat: Tell us about yourselves.

Megan Gaiser: I was CEO at Her Interactive for about 15 years. Now I’ve started a new company, Contagious Creativity, which has a lot to do with our subject.

Daniel Bernstein: I was the founder and CEO of Sandlot Games. I started it in 2002 and sold it in 2011. Since then I went out and did another startup. I’m advising startups as well. I joined an investment bank. It’s an interesting journey, but it made a lot of sense. The bank I joined is the Corum Group. We sell companies.

I don’t know if you guys know about Sandlot, but we did something very similar to what Megan did – games for an audience that’s not the traditional gamer, especially girls and women. This was an important aspect for me, thinking about leadership and creativity in a way that addresses audience that aren’t served as well today.

GamesBeat: We’re going to start with Megan. What is creativity?

Gaiser: I would say creativity is a way of being that sidesteps what’s not working to create or do something better. What’s your definition?

Bernstein: For me creativity is the generator by which new ideas happen. The newer ideas are created as a result of a fully untethered creative process. By “untethered” I mean throwing away your conceptions of what needs to be done and tapping into that inner sense that is almost something you can’t express. It’s at the bottom of who you are as a person and possibly who you are as an individual within an organization.

Tapping into that almost primal sense of who we are gives us the ability to look at the world in a whole new way. That’s what’s most exciting for me now, ideas that look at the world in a new way. Delving into the true nature of how we think about it is interesting to me.

Gaiser: I agree so much with John Cleese that I would add that creativity is our human operating system. It uses all of our senses, and both our creative intelligence and our intellectual intelligence. We tend to think of creativity as, first of all, a skill. We relegate it to making art or making products. In fact, creativity can, and in my opinion should, be used to inspire every aspect of business.

It’s about tapping into your own innate wisdom. Everyone is creative. The idea that only a certain type of person is creative is so untrue. It may be that they just haven’t tapped into it because we’re so accustomed to leading with the intellectual side — the linear, logical, literal thinking – to the exclusion of our hearts, what we care about, how to inspire. The two of those together is a full human operating system.

GamesBeat: We’re going to have plenty of arguments about what creativity is and who is creative. One way to get into this would be to ask the audience here — who either went to E3 or followed it closely? What did you think? Mike Gallagher, the head of the Entertainment Software Association, told me that he felt like there was an explosion of creativity at E3.

Gaiser: I just saw eyes rolling [in the audience].

GamesBeat: Other people go to E3 and say, “This is the same old stuff. Call of Duty again.” They have a very different reaction. Who would say they agree with Mike Gallagher? And who disagrees? Many more people in our audience disagreed. We could say there might be a problem with creativity in the game industry, if the bulk of the room feels that way.

Gaiser: Sure, there is creativity at E3. But there’s a difference between creativity and inspired creativity. It’s the same old same old. We’re not seeing the breadth of diverse stories and characters that we could be. Seeing the same old same old all the time has a dulling effect on players. It gives us a simplistic and homogenous view of what it is to be human.

We have such an opportunity now, given the past few years, which were a wake-up call. The good news is, it’s clear that the way we’re leading is not working. Disruption is creativity’s playground. This is our opportunity to flip leadership on its head.

Bernstein: You have to ask yourself, “How did we get here?” How come the games we see year in and year out are the same ones?

When you’re running a company, a public company, you need replicable revenue from hit to hit to hit. If you’re Electronic Arts and you’re looking to have an increasing level of sales year after year, and you have a captured audience base that you’re targeting—As a result of some of the things that have been happening in the markets for game companies that have gone public and shown recent earnings reports, what you’re seeing is an aversion to risk.

On the mobile side you’re seeing the cost of acquisition exceeding the lifetime value of a user. Lifetime value is how much people are going to pay for a given game. That’s the metric for a lot of the free-to-play games nowadays.

But we’re not really talking about finance here. We’re talking about creativity. All that stuff reflects a lack of desire on the part of leaders in the games industry to take risks. The risk to reward ratio is very high. You have to take a lot of risks, even if the reward is potentially tremendous. We’re seeing a kind of two-tier result. You have these large companies making a lot of money on the same types of games year in and year out. Then you have the relegation to indie. Nobody is in between. The middle class of game developers is gone. There’s no opportunity to innovate and make enough money to sustain the next creative thing you want to do.

Even if, say, ustwo, who made the Monument Valley game, comes out—It’s tremendous. It’s an incredibly creative endeavor. It’s one that cuts across gender lines, racial lines. It’s a beautiful piece of art. But because of the way it looks, the way it’s presented, the way it’s monetized, it’s relegated to the indie category.

How do we bridge that gap? How do we get to the understanding that you need to risk your capital, the understanding that you can reach incredible returns if you’re willing to invest in creativity?