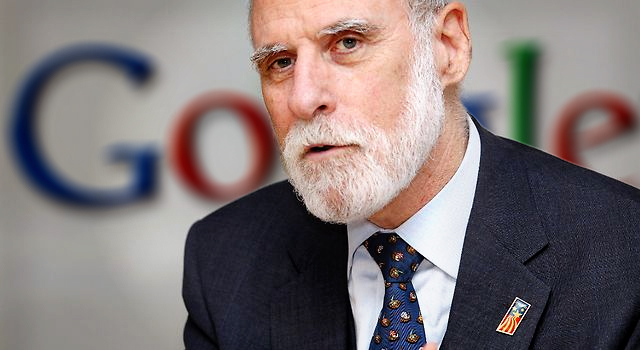

When Vint Cerf talks about Google’s upcoming global Science Fair, you can hear the infectious enthusiasm in his voice.

“I just am a huge cheerleader for getting kids interested in science and technology,” he told VentureBeat in a phone conversation yesterday.

But the Father of the Internet, who is also now a Googler, isn’t simply being patronizing. Oh, look at the kiddies playing with their toy volcanoes, how cute. He truly expects great science and fresh thinking to come from the fair’s crop of intelligent teens.

“I think there are some big surprises awaiting us in this round of the Science Fair,” he says.

“It’s important that the adults appreciate that young people are capable of doing really astounding work.”

As an example, another Googler points out 16-year old Harine Ravichandran‘s 2011 entry to eliminate power outages in rural India. This year, Google award a special “Science in Action” prize to the best project with positive, local community impact and the potential for use in other parts of the world.

Vint Cerf and the Science Fair

“The interest [in science and technology] has been difficult to stir up because we don’t give enough visibility to our scientists and technologists as we do to entertainers and sports figures,” Cerf says.

So part of the initiative to stir up such interest is the annual, global, online Google Science Fair. This year is the fair’s second in existence, and a handful of participants will be recognized for their work and awarded with prize money, scholarships and once-in-a-lifetime opportunities.

Cerf is, for all intents and purposes, the public face of the fair, which begins January 12, 2012.

“What’s really different is that we’re taking submissions in other languages,” he says. “I’m very interested to see what that does in terms of international participation.”

Of all the 13- to 18-year-old fair participants, who will create and upload their projects to Google’s site, 90 regional winners will be selected from all around the globe (barring U.S.-sanctioned countries such as Cuba, North Korea and Iran) — 30 winners each from the Americas, Europe, the Middle East/Africa and Asia Pacific. Google is offering support for 13 languages, a new effort to increase international participation.

From this group of 90, judges will select 15 finalists. Those finalists will travel to Google’s headquarters in Mountain View and will present their projects to a panel of judges (Cerf is one). The judges will then pick one finalist in each age group (13-14, 15-16, 17-18) and one grand prize winner.

As in previous years, Google is partnering with CERN, LEGO, National Geographic and Scientific American on the fair.

“I’m a huge enthusiast because it’s global,” Cerf said. “It’s an opportunity to show young people what science is all about and show the rest of the world that young people have interesting, fresh, creative ideas… and how capable our young people are in doing this sort of thing.”

Cerf on science

We wondered what sorts of science experiments from the adult world had captured Cerf’s attention, as well.

“I am very curious about the Large Hadron Collider outcomes… to see if any string theories can be validated,” Cerf told us.

“Nanotechnology has my attention, the ability to create an unnatural material that will steer light around objects,” he continued, referencing recent advances in invisibility technology. “The materials that have been created can now do this kind of bending — I find that pretty fascinating.”

But what has Cerf most intrigued, it seems, is the origin and structure of everything we know and don’t know about the very space we inhabit — the vast unknown quantities of the universe itself.

“All of this pales as we start looking at cosmology and realize that we know less now at the beginning of the 21st century than we thought we knew at the end of the 19th century,” Cerf said. “We only know about 5 percent of the matter in the universe. We don’t know what dark energy is, we don’t know what dark matter is… we don’t have a clue.”

And here’s a tip for you undecided-major types: “If you get an interest in physics, you have a shot at the Nobel Prize because anything you discover about this 95 percent [of unknown matter] is bound to be new information.”

Cerf on science fiction

When we start talking about invisibility and the universe, I note that we’re bordering on topics that used to belong in the realm of science fiction and fantasy. I point out that a recent VentureBeat speaker, Leonard Nimoy (Star Trek‘s Mr. Spock), had expounded on the migration of science fiction into science fact.

Cerf wholeheartedly agreed with Nimoy’s assessment (and noted as an aside that he had previously worked with Nimoy on a television project, during which Nimoy’s sense of humor made it impossible to shoot a scene with a straight face).

“It sounds like science fiction, but the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, they funded [Cerf’s original and groundbreaking] Internet work, the interplanetary protocols work. Now theyre funding a design for an interstellar mission to get to Alpha Centauri within the next hundred years.”

Cerf said that with our current propulsion systems, it would take around 65,000 years to reach this star — obviously, the technologist noted, this would not do.

“The second problem is communication — how do you develop a signal that will be detectable over four light years?” he asked.

“Even though I won’t be around, the idea that you coud participate in what sounds like a science fiction story… there’s nothing more exciting than that. And it’s launching in 2012.”

In other areas of science fiction, Cerf pointed to the Jetson’s-like imagined future of the mid-century era, when we thought in terms of home automation and self-flying cars.

Again, Cerf sees some aspects of that fictional world becoming reality, especially with regard to the Internet of Things. “The Android OS is turning out to be of interest… in other devices, things that consume electricity, appliances around the house,” he said.

And of course, there’s Google’s revolutionary self-driving cars.

“We’re very proud of those cars,” said Cerf. “This is turning out to be an incredible period of time when we’re able to harness the power of computing in small devices and also harnessing huge computing power in the form of clouds.”

Cerf on technology and government

It’s exhilarating to talk with this living legend about futuristic science and technology as it unfolds around us, but I know that Cerf sees more than a few threats to innovation, too.

At a recent conference on cloud computing, Cerf stated that he felt the government was overstepping its bounds in censorship of the Internet. Speaking about the Department of Homeland Security’s recent seizures of websites, he said such measures were “a blunt instrument that can and should be exercised much more carefully.”

In our phone conversation, Cerf expounded on that theme.

“The government has a responsibility to protect society, to help maintain society. That’s why we have laws… The rule of law creates a set of standards for our behavior,” he said.

“But there are extremes in both directions that don’t work very well.”

There is such a thing, Cerf explained, as too much privacy. Privacy for criminals would allow people with bad intentions to carry out their nefarious deeds unchecked. On the other hand, too little privacy would result in a crime-free utopia that would also be “unpleasant,” said Cerf, “because everybody knows everything” about their neighbors, their subordinates, et cetera.

“Where to draw a boundary between those two tensions so we’re protected from harm but we maintain a reasonable privacy in our affairs” is key, he concluded. “Finding that balance would be one of my highest priorities.”

But Cerf was speaking about how he would conduct himself if he were in charge of our government’s actions. As a technologist, what can he do? How should technologists approach this problem of stemming the tide of legitimate online crime while protecting freedom of speech and privacy?

“We have a responsibility to protect people and businesses from harm in the environment we’re working on,” Cerf said, continuing to say that developers, entrepreneurs, innovators and executives need to work with regulators on these issues so that the good things about the Internet can be preserved at the same time.

“I am so worried about SOPA and PIPA, I’m worried about governments that want to control access to and use of the Internet,” said Cerf. “There really are problems with privacy, with malware, with fraud. Those are all real problems, but we need to be thoughtful about how we go about solving those problems. You don’t want to kill the goose that’s laying the golden egg.”

Cerf on the future of technology

Our conversation moves back to the more pleasant topic: that of the golden egg. As our world takes on more of the trappings of science fiction, many technologists are predicting that some level of coding expertise will be a necessary skill in the next few years.

In fact, a few startups have been built around the idea that tech novices must learn how to write basic code. For example, Codecademy teaches JavaScript coding through a simple interactive interface. One of the company’s young founders, Zach Sims, told VentureBeat he sees code-writing as a very important skill for would-be employees over the next few years.

“While the entrepreneurial community has exploded within the past year or two, there’s a constant shortage of developers and a tremendous number of businesspeople trying to learn to code,” said Sims. “Programming literacy is going to be an incredibly important skill in the next few years, and we hope we can bring that to new groups of people.”

While Cerf acknowledged that coding is a valuable skill, he said that the increasingly common insistence that writing code will be a necessary function of daily life is “hyperbolic, from my point of view.”

Rather, he thinks code will continue to happen in the background, enabled by applications with layers of abstraction between human and bare metal.

“A lot of people who use spreadsheets on a daily basis don’t think about it as coding, but it is. It’s just simpler than if you were writing an operating system,” he said.

“Tech has allowed peole to cause software to happen… which is why the application space has been so vivid, more people are capable of doing it because it’s been made simpler.”

Ultimately, Cerf said, we will end up creating more code as byproducts of our actions, but we won’t be doing the programming ourselves.

“I hope it won’t be necessary for people to be programmers, but it is necessary for people to have an appreciation for what is possible because of science and technology… an abstract understanding of how things work.”

Cerf on moral technology

Finally, as our conversation came to a close, we drifted toward the topic of a recent op-en Cerf penned for the New York Times.

In this article, Cerf maintained that Internet access is not a human right. Nor, he said, is it a civil right. Rather, the Internet is simply a tool that has the potential to unlock new levels of access to human and civil rights.

He wrote,

“Yet all these philosophical arguments overlook a more fundamental issue: the responsibility of technology creators themselves to support human and civil rights. The Internet has introduced an enormously accessible and egalitarian platform for creating, sharing and obtaining information on a global scale. As a result, we have new ways to allow people to exercise their human and civil rights.”

This statement puts a large onus on us, the technologists, to constantly remember how closely our work connects people to possibilities, to freedoms, to expression, to information.

But, I asked Cerf, don’t we too often forget that responsibility? What about the apps we make that lack redeeming value or that actually serve to augment discord and apathy?

“I would like to imagine that technologists would feel that moral obligation,” Cerf responded.

He gives a great example: “I would love to see a version of Angry Birds that lets you go in and change the physics of the environment — the gravity, the elasticity — to give the players a sense of how the physical constants of the world work…

“What would Angry Birds be like if you tried to play it on the moon?”

It’s at least an educational premise and at best an idea that could turn millions of hours of mind-numbing entertainment into — who knows? — a solution to bridge that 65,000-year gap between Earth and Alpha Centauri.

“The kids are already excited about playing the game, it might be a very interesting experiment.”

Photo for image courtesy of Joi Ito.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More