How the Supreme Court left itself a window to regulate virtual reality

In 2011, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled on Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, and it found that video games are protected speech under the First Amendment to the Constitution. This struck down a California law that would have limited the sale of violent and sexual games to minors.

Justice Antonin Scalia authored the majority opinion.

“Like the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them, video games communicate ideas — and even social messages — through many familiar literary devices (such as characters, dialogue, plot, and music) and through features distinctive to the medium (such as the player’s interaction with the world). That suffices to confer First Amendment protection.”

That ruling made immediate sense to many people who see games as just the latest scapegoat for a society that had previously blamed comic books and rock music for its woes. This decision would also seem to close the door on any debate regarding gaming’s relation to the First Amendment, but it actually doesn’t thanks to Justice Samuel Alito’s concurring opinion.

Alito, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, wrote that he agreed the California law was too broad, but he wanted to leave open the possibility that the law should judge games on a double standard.

“This is Justice Alito saying that games are protected by free speech but virtual reality is so immersive and so qualitatively different that he wants to flag for precedent that this might be extremely different moving forward,” said Bailenson.

The Stanford professor is especially qualified to speak on this as Alito referenced Bailenson’s book Infinite Reality in his opinion.

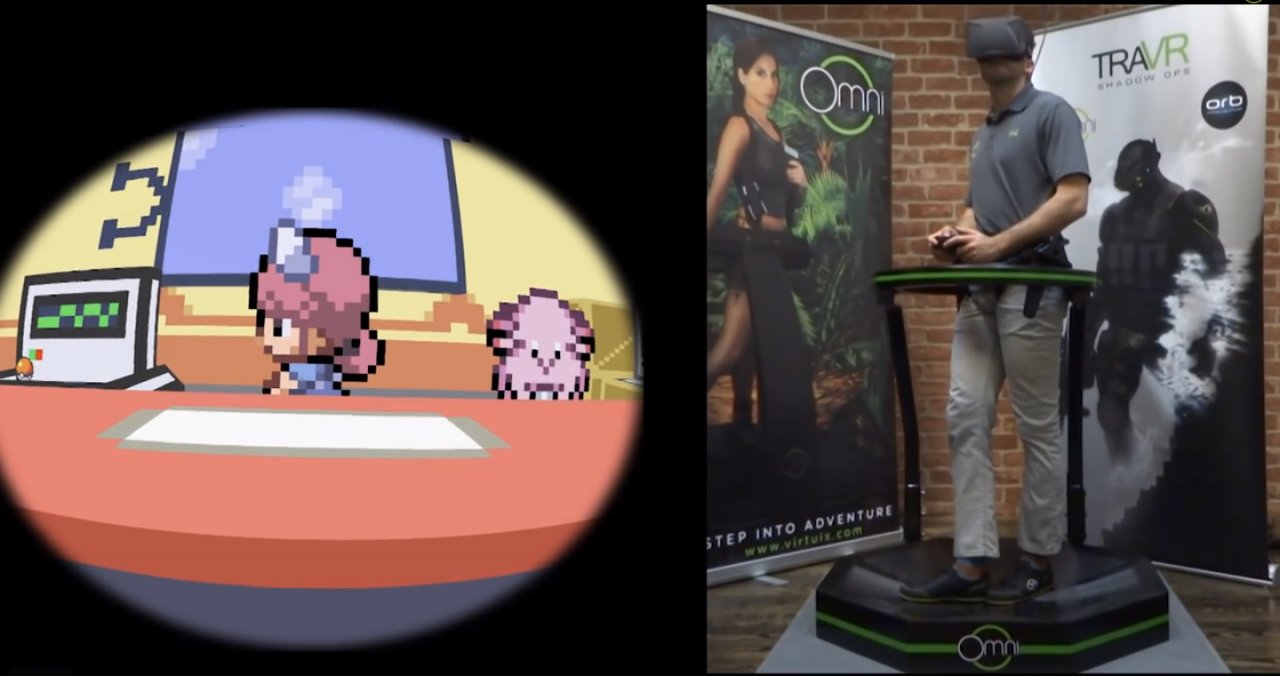

The question is whether virtual reality is so much more than reading a book that it goes beyond mere expression and affects a person in a way that is more like a drug or controlled substance.

Luckey says that he already sees people calling for government-imposed regulation on virtual reality, and he expects that group will get larger and louder as Oculus Rift gets closer to release.

“But that’s what happens with every new technology and every new medium,” said Luckey. “People come out of the woodwork. First the crazies, then the mainstream, and then everyone realizes that it’s all OK. There are going to be people that make all kinds of arguments against freedom of speech. But freedom of speech isn’t about optimal outcome for the most people. It’s about having the freedom to keep the public informed and not to be oppressed in what you say. If you accept that, then there’s no way that VR should be controlled any more than another medium.”

The National Coalition Against Censorship agrees with him. GamesBeat spoke with the organization, and it echoed Luckey’s position that even if VR does have a negative effect on some people, that doesn’t matter because it’s unclear who should get to decide what is and isn’t permitted.

Bailenson, however, is conflicted.

“Immersive VR is different in many ways from watching a movie or reading a book,” he said. “And yeah, it’s free speech. But man, we really have to think about this.

“It’s nuanced. Sure, you can feel high presence when you’re reading a book — the same way when you are highly immersed in VR. What makes this technology different is that virtual reality completely tricks the brain on a perceptual level. Your eyes and ears and skin — they react to the simulation as if it is fundamentally real.”

While Bailenson is advising caution, Oculus VR is charging ahead, and the device is very likely going to come head-to-head with public outcry from people who see virtual reality as the culmination of all their worst fears about video games. And with Alito’s opinion on the record, Brown v. EMA‘s precedent won’t cover VR, which means society will probably once again have to determine whether an interactive medium is protected expression … only this time the evidence may suggest it really is something more.