There are six words that no security or technology professional ever wants to hear:

“We have a confirmed data breach.”

Almost everything we do in our enterprise security programs as leaders, or consultants, or programmers, or analysts, or ethical hackers, or trainers, or company business executives or (fill in the blank with another role including end users) is intended to prevent the moment when those words are said.

If you’ve ever been the person accountable for security and heard those words spoken, you know that terrible sinking feeling.

For others, here’s an (imperfect) analogy: Think of how you would feel if you heard a doctor tell you that your tests came back positive and you do, indeed, have cancer.

But here’s a reality check to remember: Data breaches happen more often than most people think. John Chambers, CEO at Cisco, reportedly said, “There are only two kinds of companies. Those that were hacked and those that don’t yet know they were hacked.”

Not all data breaches are created equal

Back when I was the Michigan Chief Security Officer a few years ago, I got a call from another state technology leader who wanted a listening ear and some advice for the future. He’d just been interviewed by a local news reporter who asked him several questions on cybersecurity.

The reporter was friendly and helpful, but he was seeking reassurance that the state’s citizen data was being safely and adequately protected. He was looking for a feel-good story with the basic message “everything is fine here.” Since this was shortly after South Carolina’s data breach of more than 3.6 million records, my friend was especially concerned with his answer to one simple question: “Has our state experienced a data breach?”

Feeling caught off guard on this question, he said, “I am not at liberty to discuss this topic.” The truth is that his government had experienced a (very small) security breach in one department several months earlier, but he certainly didn’t want to talk about it to the press. No one wants to be in the headlines for an accidental news story that reflects badly on his/her organization.

Since most states have breach notification laws, the reporter was clearly expecting a transparent yes or no answer — followed by a discussion of any relevant “yes” details. Since this reporter was trying to write a supportive story, he was surprised by the answer. Needless to say, the reporter’s reaction spooked my friend, leading to the phone call to me.

Data breaches can be minor

I think this kind of dilemma is one that security and technology professionals face quite often. Of course, no one, including my friend, wants to lie. Furthermore, very few can say an unequivocal “no breaches” without adding some caveat such as “that I am aware of” or, more likely, “we’ve had no major breaches.” Still, who wants to explain the difference between major and minor breaches?

Digging even deeper, answering the breach question often gets somewhat complicated. Explaining a “minor breach” is a bit like telling your spouse you have easily treatable cancer. No one likes hearing the word “cancer” — even if the odds are good for a full recovery. Allow me to explain with a “very minor breach” story from Michigan government.

Once upon a time, we had a vendor who won a small contract award. The award announcement was supposed to be placed on a purchasing Web page in a secured area where only authorized vendors can gain access. However, the award announcement was mistakenly placed on a public-facing website. Since this contract was awarded to a sole proprietor, the company identification number listed was also that person’s Social Security number. Bottom line: This sensitive data was temporarily available to the public for more than 24 hours until the error was discovered and fixed.

In simple terms, we experienced a (very minor) data breach of one person’s sensitive information. In keeping with Michigan notification laws and internal government processes, the person was notified and the appropriate follow-up actions, such as issuing free identity theft protection, were taken.

While this type of internal error leading to a breach is rare, I believe that very small data breaches do occur in business offices more often than people realize. In the vast majority of cases, appropriate actions are taken to safeguard consumers and lessons are learned by staff regarding how to prevent future mistakes.

It’s time for a data breach scale

Which brings me back to the original question — and my answer.

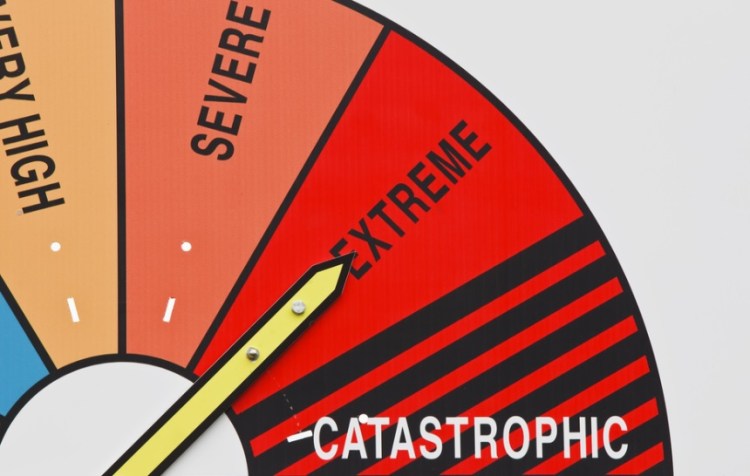

I think it’s time for some type of a data breach scale. The scale could be similar to the Richter scale for earthquakes or the measurements for various stages of cancer or perhaps the different levels that weather forecasters use to describe tornadoes.

The purpose would be to describe more clearly the different types and scale of data breaches — and perhaps other types of cyber incidents such as denial of service attacks or destruction.

No doubt, there are plenty of details to work out. Who would decide? What would be included? When can we start? Where do we go to arbitrate? Do we need new laws, or would the scale just a general guideline? Would there be international recognition of the scale? And is it even worth the effort?

I have plenty of possible answers, but I don’t want to go there right now.

However, I would love to hear your opinions on this. Is it time for a data breach scale? Why or why not? If yes, what would be the best next steps?

Dan Lohrmann is chief security officer (CSO) at Security Mentor. Prior to joining the company, he was Michigan’s first CSO and Deputy Director for Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection from October 2011 to August 2014. Under his leadership, Michigan was recognized as a global leader in cyberdefense for government. He currently serves on the Michigan InfraGard Executive Board. Over the past decade, Lohrmann has advised the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the White House, FBI, numerous federal agencies, law enforcement, state and local governments, non-profits, foreign governments, local businesses, universities, churches, and home users on issues ranging from personal Internet safety to defending government and business-owned technology and critical infrastructures from online attacks. Lohrmann represented the National Association of State Chief Information Officers on the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s IT Government Coordinating Council from 2006-2014. In this capacity, he assisted in the writing and editing of the National Infrastructure Protection Plans, sector specific plans, Cybersecurity Framework, and other federal cyber documents. Lohrmann’s first book, Virtual Integrity: Faithfully Navigating the Brave New Web, was published in November 2008 by Brazos Press. His second book, BYOD for You: The Guide to Bring Your Own Device to Work, was published in Kindle format in April 2013.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More