The next evolution of the Internet or so-called “3.0” is supposed to be semantic, smart if you will. Smart, automated social tools were all hyped to go viral at this year’s SXSW conference several days ago. These tools promise to turn us, via our smartphones, into all knowing masters of our environment, prompting us to meet new friends at IRL serendipitous moments. But, instead, the big story turned out to be the short lifespan of these apps. All of these Location Based Services (LBS) apps focus on hooking into your friends on Facebook, Linked-In, and Twitter and alerting you when “real” friends entered your “geo bubble” of life. They also suggest new friends or friends of friends that you should meet.

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":406392,"post_type":"guest","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,mobile,social,","session":"D"}']The technology worked – I was alerted to many people that I should meet who “liked” the same stuff on Facebook; but that turned out to be boring, as our common interests turned out to be only fan pages for TV shows or bands. I was also alerted that friends were nearby. Alas, friends that I wanted to see I had already texted or rendezvoused with.

In fact, these apps didn’t fly with the social early adopters at the show for an important reason: They caused smartphone batteries to die, leaving attendees at a social conference without the ability to be digitally social. No tweets, texts, photos, or profile updates get pushed when your iPhone goes dark. The problem at hand with LBS apps is that they require the GPS radio to run nearly full-time, have a clear view of the sky to get a signal, and report back to a server their location.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

When you’re using your smartphone for navigation, your windshield and roof barely block the signal, and typically your cigarette lighter adapter keeps the juices flowing during this peak power usage. When your phone is in your pocket or purse, your body acts as a Faraday cage, blocking GPS signals from reaching it as it struggles to get a position.

I like to say that GPS stops at the door. (Full disclosure: I run a company that’s betting WiFi and Bluetooth will steal the market from GPS for location-based apps.) Companies like Google are taking rolling carts with sophisticated WiFi measuring gear through airports and malls, using the retailers’ access points to physically map them into a virtualized GPS. This enables the Android Maps application to move the blue dot to about the same spot in which you stand. This results with WiFi working much like the GPS satellite system does to the Maps application on your smartphone when you’re outside.

But life is more than your virtual representation as a blue dot. Inside, maps are boring. I can find the bathroom with signs, and the registration desk via arrows. Instead, think of the potential for radio waves as triggers for actions to occur in your phone, or in the cloud – making intelligent decisions automatically while your phone sits in your pocket. And unlike GPS, which requires a clear view of the sky, Bluetooth and WiFi radios inside your phone work inside the confines of your walls and halls.

Your smartphone has WiFi, which normally requires you to connect to an access point, and Bluetooth which requires pairing to another device to communicate. Using these same radios without the need for connecting, when you walk into a specific space, your dating app could alert you to a suitable match (after you enable ice-breaking in-room digital serendipity), or your social networking or business app could let you know when a friend or to-be customer is within eyesight. Maybe your mobile phone calls could get routed to a landline for drop-free calling. All without compromising your smartphone battery. Now that is true social and smart innovation.

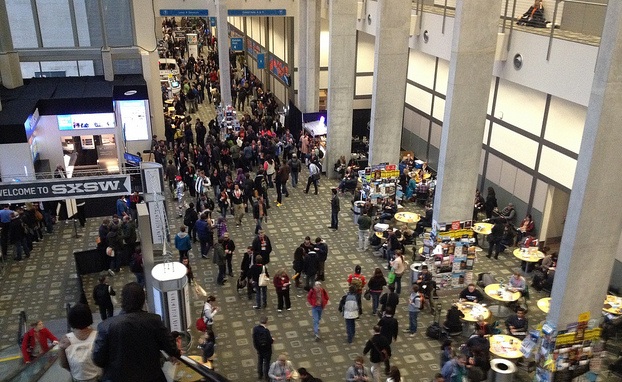

[SXSW image credit: Kevin Krejci/Flickr]

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":406392,"post_type":"guest","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"business,mobile,social,","session":"D"}']

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More