History may anoint 2016 as the dawn of the modular smartphone era. Headline after headline breathlessly crowns handsets like the LG G5 and Motorola Moto Z as the first to offer users some degree of hardware customization. But is this a false narrative, one which confuses true modularity with sets of functionality-enhancing accessories? Or do these devices simply offer proof that the very first modular phones won’t achieve the lofty expectations set by Motorola’s (now Google’s) initial Project Ara — which itself no longer strives for full modularity?

To be fair, the definition of “modular smartphone” isn’t written in stone. As an example, an upcoming consumer device from Google that describes itself in those terms, Project Ara, has dialed back its ambitions significantly in the past year, choosing not to replace some of its most core components.

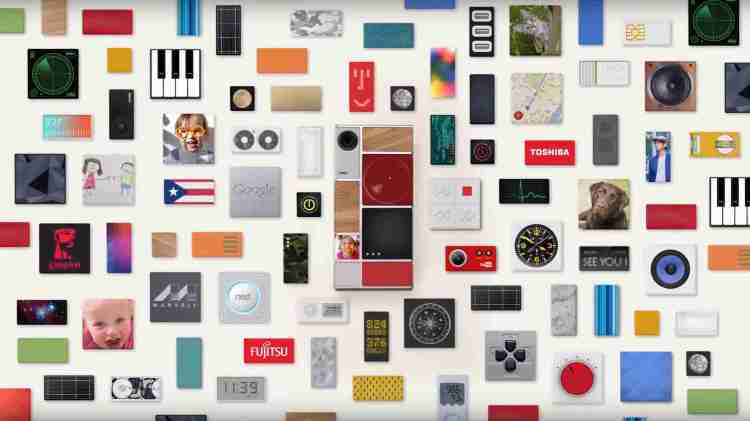

Ara’s original concept, a hub around which a modern smartphone’s most essential components could be interchanged at will, may be what most people see when they imagine modularity. And that’s because this view mirrors the way enthusiasts have built their own personal computers for many years.

In the PC industry, an analog to the modular smartphone already exists in the form of do-it-yourself computers whose parts can be assembled from a wide array of vendors. When you build your own PC, it’s not a big deal to continually upgrade pieces of it over time. My own machine has existed in several forms over the past decade, all housed in the same enclosure I bought in 2006.

But pocketable phones are several degrees more complex than desktop computers, whose physical space constraints are much less limited. This seems to be why the original Ara concept was scrapped: With so much space needed for CPU, RAM, storage, and battery modules, there was little room left on prototype frames for modules that would allow for handset customization and differentiation.

This is a trade-off that questions the very purpose of a modular smartphone: Does the phone exist to offer upgradability and reduce e-waste, or is it a blank slate for encouraging customization and enhancing functionality?

Ara is moving forward with the latter philosophy, arguing that people aren’t as interested in worrying about the components that power their phones as they are in adding features that go beyond out-of-the-box functionality. But one person who has worked closely with the Ara team since nearly the beginning, when the project was still part of Motorola, isn’t a fan of the pivot that’s been made.

That person is Dave Hakkens, a Dutch designer who, in 2013, posted a video that ignited much of the current global interest in modular smartphones (it’s been viewed over 20 million times, to date). In the video, Hakkens details his vision for a completely modular device ecosystem called Phonebloks.

Hakkens is primarily interested in the concept from an environmental viewpoint, not simply for the geek factor of assembling a working smartphone out of standardized parts. He sees the commoditization of consumer electronics, especially the throw-them-away-every-two-years smartphone, as a pressing environmental threat.

For Hakkens, and many others in the Phonebloks community, the ability to interchange (and thus, upgrade) core components — like the system-on-a-chip, RAM, and storage capacity — is critical in any modular ecosystem. Currently, none of the self-proclaimed modular phones from large corporations (LG’s G5, Lenovo’s Moto Z, Google’s Project Ara) offer this. But all hope is not lost, as other, smaller companies are beginning to step in with their own solutions.

Right now, the project that most closely resembles the idealized modular phone is from a Finnish company called Circular Devices. Its PuzzlePhone, which has raised $116,000 in crowdfunding through an Indiegogo campaign and is due to start shipping this year, has a trio of modular components designed to stave off obsolescence. Called the brain, the spine, and the heart, they represent the CPU (system-on-chip, really), the display, and the battery, respectively.

PuzzlePhone offers true modularity in the sense that it can be upgraded, albeit only partially, with faster processors; bigger, more efficient batteries; and higher-resolution, better-looking screens. Company CEO Alejandro Santacreu claims that the targeted lifespan of this Android-powered handset is a staggering 10 years. Compare that to your average Galaxy or iPhone, which not only feel wholly obsolete after two or more years, they lose manufacturer support and platform upgrades at around the same time.

Next up is the Fairphone 2, an ethically sourced Android handset that contains numerous hardware components capable of end-user replacement. In fact, the only thing keeping this device from matching the DIY computer market is the lack of a rich ecosystem of replacement parts from multiple vendors — although if the phone eventually achieves a foothold with mainstream users, that could possibly change.

Finally, a company in China named Seeed Studio offers a completely different take on a modular communications device. Its RePhone kit isn’t a traditional smartphone at all, but its small screen, inexpensive price tag, and open source operating system make it perfect for adding cellular capabilities to all sorts of applications where a smartphone would be either cost-prohibitive or too delicate to incorporate. One of its more innovative features is a template that can be used to build its enclosure using all sorts of different materials, from cardboard to leather to a 3D printer-created hard case.

That brings us back to the initial question: If 2016 is indeed credited as the dawn of smartphone modularity, will that be an accurate view or one seen through rose-colored glasses? The truth is, it could actually be both.

If, on the one hand, big-name devices like LG G5 and Lenovo Moto Z are said to represent those first steps, then the claim would be a bit disingenuous; after all, functionality-enhancing hardware add-ons have been around since the days of the Palm-powered Handspring Visor.

But if we loop projects like PuzzlePhone and Fairphone into the mix, the argument becomes much more cogent. The bottom line is this: No matter which year ultimately delivers modularity with commercial appeal, the genie is already out of the bottle, and enough imaginations have already been fired up to ensure that the concept is unlikely to die.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More