For my entire life, I’ve relied on habit. I wake up when my eyes open in the morning (sometimes prompted by the alarm clock), eat when my tummy says its time, exercise in the mornings, and fall asleep when I’m dead tired.

For my entire life, I’ve relied on habit. I wake up when my eyes open in the morning (sometimes prompted by the alarm clock), eat when my tummy says its time, exercise in the mornings, and fall asleep when I’m dead tired.

But the applications being built for the latest “3.0” version of the iPhone operating system — and likely soon for a number of other smartphones — promise to monitor my every step, my cycles, my health, constantly, via sensors on my skin. They may make me even more efficient.

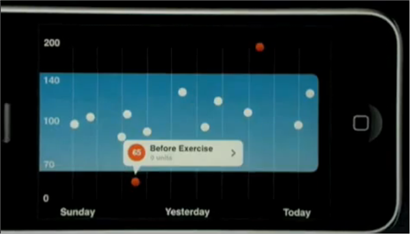

Right now, they’re focused on people with serious ailments. Last month, LifeScan, a Johnson & Johnson company focused mainly on diabetes monitoring devices and software, demonstrated a Bluetooth-enabled blood glucose monitor that syncs with the iPhone’s 3.0 operating system. The video demo is below. The iPhone 3.0 OS, to be released sometime this summer, lets the phone interact with other devices, thus making all this possible.

Looking forward to this, a bunch of companies are working away on applications that monitor all of your six vitals: These vitals are temperature, heart rate, heart rhythm, respiration rate, blood pressure and 02 saturation (or the amount of oxygen you have in your blood). I’m told there’s no reason that all six vitals can’t be tracked from a single sensor — which would then be synced to a phone application via Bluetooth. With all that information, the phone could do some cool stuff: If you drink too much caffeinated coffee on an empty stomach, your phone might be able to alert you that you’re extremely agitated and that you may want to cool off before you slap your annoying office-colleague upside the head.

The Lifescan application (screenshot at left) was created as a prototype for Apple to show off the iPhone 3.0’s capabilities — which allow companies to build apps customized for external devices like a glucose meter — but the product is not ready for commercial launch. Why use an iPhone, instead of the non-phone version of the wireless software? For one, LifeSpan says diabetics often feel lonely, and hooking up to the iPhone will let them communicate with others using social networking features.

The Lifescan application (screenshot at left) was created as a prototype for Apple to show off the iPhone 3.0’s capabilities — which allow companies to build apps customized for external devices like a glucose meter — but the product is not ready for commercial launch. Why use an iPhone, instead of the non-phone version of the wireless software? For one, LifeSpan says diabetics often feel lonely, and hooking up to the iPhone will let them communicate with others using social networking features.

This is all really early. Two partners at a top Silicon Valley venture firm told me last week they want to invest in such medical applications on the iPhone. They won’t have to look far, because there are scores of companies like LifeScan that are already monitoring vital signs wirelessly. All these companies need to do is build applications for smartphones.

Some companies, such as Toumaz.com, are building tiny sensors priced at $10-20 that you can use to track your vitals such as heart rate, and which could be easily connected to a smartphone. A stealthy company called Adigy is working on something similar, but they’ve yet to build a mobile app. Cardionet, of San Diego, is one of the bigger players doing heart rate and rhythm wireless monitoring and says it is building a mobile application. Triage Wireless, backed by Qualcomm Ventures, is one of many that monitors blood sugar levels and other vital signs wirelessly in hospitals and homes, but it hasn’t released a mobile phone version.

Signs are strong that such apps will be entering our lives in a big way within the next five years. Experts say they’ll give you a visualization of your daily rhythm of life and will encourage you to eat and sleep the right amounts at the right times in order to enjoy your life to the fullest. Lots of companies, such as Zealog, are trying to help people track their activities on the Web already, but they’re mostly primitive without being linked to your life on the go. There are still several challenges. For one, monitoring isn’t perfect, because of background “noise” that interferes with the translation of things like your heart pulse via Bluetooth, but companies are building algorithms to correct for this. Some people don’t like the electrical gel and wires used with some of the sensors. Finally, medical applications generally require FDA or other regulatory approval to have credibility. Some say sports applications will thrive, offering specialized data, but avoiding the need for FDA blessing.

Hitachi of Japan offers a watch-like device that lets you track your pulse, skin-temperature and bodily motion. In Korea, device maker LG has the KP8400, which is a cell phone that comes with a glucose monitoring strip, giving you insulin and blood readings on the phone’s display. And there are other efforts already on the iPhone, such as Proactive Sleep, which attempts to figure out your sleep cycle and then acts as an alarm to wake you up during your light sleep phase to maximize your alertness for the rest of the day — but frankly, it doesn’t seem that sophisticated because it’s not actually monitoring you live.

Of course, you don’t necessarily have to hook up the sensors to your phone. You could hook them up to some other access point, and transmit activity on the Web — like the NYT graduate student who developed vibration sensors for his pregnant wife to alert Twitter each time the baby kicked. Another company, Fitbit, also offers a device that can be clipped to your clothes, then monitors things like how many calories you burned and how many hours you slept.

[By the way, if you’re an entrepreneur with a cool idea or product you’d like to consider launching at one of our conferences, including the leading launchpad conference for tech products, DEMO, please get in touch with us.]

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYUyNeAzcbc&hl=en&fs=1&w=560&h=340]VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More