Update: This article is now available as a 63-page e-book on Amazon’s Kindle bookstore.

Zynga has turned the video game world upside down in its short five-year history. As it’s poised on the verge of a massive initial public offering, the social game startup is now one of gaming’s great success stories.

But its success was never a foregone conclusion. In fact, most game industry veterans didn’t view it as a real game company. Mark Pincus was a four-time entrepreneur, but had no experience in the game industry and had never managed a big company. He was the most unlikely entrepreneur to create a game industry giant.

Now Pincus is set to become a multibillionaire as the largest shareholder in a company that is about to hold on Thursday one of the biggest initial public offerings of the year. Zynga’s billion-dollar IPO, at an $8.9 billion valuation, will be one of the biggest events in gaming history and will make it a financial peer to established rivals like Electronic Arts and Activision Blizzard. Through the IPO, Zynga hopes to meet the ambitious goal of investing more “in play than any company in history.”

And it is possible in no small part because Pincus, the gaming novice, dreamed bigger than the game industry when it came to giving users accessible and social games, anytime, anywhere. Against all odds, Zynga has out-competed big gaming brands in the great social game Gold Rush. Zynga games have continuously held the No. 1 ranked spot on Facebook since the beginning of 2009. As of today, it has five of the top five games on Facebook.

Pincus couldn’t have done it on his own. Along the way, he has been helped by the fortuitous friendship of gaming veteran Bing Gordon. Facebook insider Owen Van Natta played a key role at a critical time. And experienced game designers like Mark Skaggs and Brian Reynolds have led the creation of innovative, addictive games, helping the company rise above its early reputation as a creator of cheap knockoffs and a persistent spammer of Facebook news feeds. Together, these people helped Zynga get where it is today, while rivals like Playfish and Playdom decided to take earlier, less lucrative exits.

Since its inception in 2007, Zynga has generated more than $1.5 billion in revenues — a remarkable sum for such a young company. It is now trying to seize the leading share of a $9 billion virtual goods market that it believes could triple in the next five years.

Now the company’s ambition is to become as synonymous with play on the internet as Google is with search, Amazon is with shopping, and Facebook is with sharing. It was lucky that Zynga started out with so little game experience in the beginning. But throughout its life, it would have to prove over and over again that it was a real game company that mattered.

In the following pages, I’ll tell the tale of Zynga from its earliest days. This story is based on extensive interviews and research since 2008. We’ve had limited access to Mark Pincus. In recent months, he hasn’t been giving interviews, due to a quiet period mandated by regulators. But the story of Zynga isn’t just about the founder of the company. It’s also about the whole cast of characters who surrounded him, the rivals who drove him to succeed, and the industry that challenged Zynga to prove itself over and over. We’ve done our best to triangulate on how Zynga became what it is today — and how it almost didn’t happen.

Humble beginnings

Cast of Characters

- Mark Pincus, the founder and CEO

- Bing Gordon, the game executive and “consigliere”

- Owen Van Natta, Zynga business executive, former MySpace chief

- Mark Skaggs, Zynga general manager for FarmVille and CityVille

- Brian Reynolds, Zynga’s chief game designer, creator of FrontierVille

- David Ko, Zynga’s senior vice president for mobile

- Roy Sehgal, game designer and general manager of Cafe World

- John Schappert, chief operating officer of Zynga and former COO of Electronic Arts

- Cadir Lee, chief technology officer of Zynga; co-founder of SupportSoft with Pincus.

- Allan Leinwand, Zynga CTO for infrastructure engineering

- Colleen McCreary, Zynga’s “chief people officer”

- Bill Jackson, creative director at Zynga Dallas and CastleVille

- Yuri Milner, investor at Russia’s DST

- John Doerr, partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers

- John Riccitiello, CEO of rival Electronic Arts

- John Pleasants, former CEO of Playdom, now head of Disney Interactive Media

No one would have pegged Pincus as a game tycoon. The Chicago native went to study business as an undergraduate at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. After graduating, he worked in finance at Lazard Freres and Asian Capital Partners. He went back to get an MBA at the Harvard Business School and graduated in 1993. Then he bounced around at a number of jobs.

“I had a lot of careers before I became an entrepreneur,” Pincus said in a speech about starting companies at Startup Berkeley in the spring of 2009. “And I failed on other people’s money. If you were trying to become a professional athlete, you would want to go through junior leagues first before you started a pro circuit. Fail a lot before you are paying for the failure….I got fired or asked to leave from all my jobs.”

The option that was left for him, Pincus joked, was to become an entrepreneur. He had read George Gilder’s book, Microcosm, and was excited about the economics of the world enabled by technology. That drove him into new media. He eventually made his way to Silicon Valley, starting FreeLoader, a web-based push company, in 1995 with a $250,000 loan. That company was acquired after seven months for $38 million by Individual. It was the start of Web 1.0, or the first giant wave of the first real internet companies.

At the time, other tech companies were selling out for hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars, making Pincus’ exit look almost paltry. Still, his first startup success gave Pincus a full membership in Silicon Valley’s dot-com era. He then founded Support.com (later SupportSoft), a provider of service and support automation software, along with Cadir Lee and Scott Dale. The company went public in July 2000.

Flush with cash, Pincus co-founded his own incubator, Tank Hill in January, 2000. It was just in time for the dot-com crash, and he and his partner shut it down and returned the funds nine months later. In 2003, at the age of 37, he started Tribe.net, one of the first social networks. Pincus thought of it as a “Craigslist meets Friendster.” That didn’t work out so well. Pincus left in 2005, after the board threw him out. In 2006, he took it back over from the investors and sold its assets to Cisco. At the time, Tribe.net had just eight employees, and Cisco completed its purchase by March 2007.

He teamed up with his friend Reid Hoffman, a PayPal veteran and now founder of LinkedIn, to buy a patent on social networking from the defunct Sixdegrees for $700,000. Then they invested in a little company called Facebook, which turned out to be at the beginning of the Web 2.0 wave of companies, or those that were built to take advantage of a newly dynamic web and its growing network of interconnected users. That put Pincus in close touch with Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and gave him the inside track to the social media revolution.

Pincus is on record as starting four companies, but he said there were 15 or 20 projects that failed. But Pincus did have a nice touch as an angel investor. His investments included Napster, eGroups, Technorati, Socialtext, Friendster, Ireit, Nanosolar, Merlin, Naseeb, EZboard, Advent Solar, Xoom — and Facebook. Noticeably absent from that list were any game companies.

Making the right bet

To get to Zynga, Pincus said he had three formal failures, including Tribe.net. Another failure was an ad company called Tag Sense. From that, he concluded, “Don’t go start a company just because you have a customer and someone will fund you. If it is a marginal idea, that’s bad.”

Because Tag Sense failed quickly, Pincus said, he was ready when, in the May 2007, Facebook opened up its applications programming interface, inviting other companies to make applications on top of its social network in hopes of beating MySpace. That move helped Facebook gain users as well as developers, creating a virtuous circle. Pincus decided to go along for the ride.

Previously, Pincus had been operating under the name Presidio Media, a company which he formed in April, 2007, as part of an effort to jump on the Facebook bandwagon.

“The whole time I was doing Tribe, I thought the thing I would have loved to do is games,” Pincus said in a 2009 interview:

“The whole time I was doing Tribe, I thought the thing I would have loved to do is games,” Pincus said in a 2009 interview:

I’ve always said that social games are like a great cocktail party: You’re happy at first to see your good friends, but the value of the cocktail party is in the weak ties. It’s the people you wouldn’t have thought of meeting; it’s the friends of the friends….What I thought was the ultimate thing you can do — once you bring all of your friends and their friends together — is play games. I’ve always been a closet gamer, but I never have the time and can never get all of my friends together in one place. So the power of my friends already being there and connected, and then adding games, seemed like a big idea.

In July 2007, Pincus changed the name of his new company to Zynga, named after his late bulldog, Zinga. Zynga’s first headquarters were in the Chip Factory in the Potrero Hill neighborhood in San Francisco.

From his previous experiences, Pincus learned, “Control your destiny. We all write this story for ourselves that we were really successful and the evil VC came in and f***** up our company. They backed us and got rid of us and if they had just left us alone. That’s everybody’s sob story in Silicon Valley. You f****** it up because you gave them control of it.” He said he would settle for half the valuation if he could control his company and destiny. As a result of that desire, he funded Zynga himself.

The early team included Eric Schiermeyer, Michael Luxton, Justin Waldron, Kyle Stewart, Scott Dale, Steve Schoettler, Kevin Hagan, and Andrew Trader. Pincus was intense and drove them hard, but he wanted to build a great company.

Its first successes were on MySpace, where other social game companies were making money from ad-based games. Zynga’s early revenue came from MySpace, but Pincus had the smarts to realize that Facebook would win in the future. It was a smart bet that helped Zynga to catch Facebook’s coattails as it went through an unprecedented wave of growth.

As he tried out ideas, he kept in mind that he should test them as cheaply and as quickly as he could.

The company released its first game for Facebook in September 2007. It created a free social poker game on Facebook, chosen because it was simple and it was a universal game that enabled friends to plan a “poker night” with each other no matter if they were far apart or not. Zynga was riding a wave of resurgence that poker had seen since 2003. Zynga’s first game was successful enough to make the company profitable.

“We were the first company to believe in the social gaming opportunity and go after it with our poker game in July, 2007,” Pincus said in an interview with VentureBeat in 2009. “Everybody else was focused on viral apps like pokes and other things that spread more virally. We were always interested in just the gaming opportunity. By the time we saw it was real and had a sustainable revenue stream, we were the first to start investing deeply in it.”

Before Zynga, free games were often viewed as low-quality shareware. But now they were something that millions of people could enjoy. The poker game gained users for a while, but it had no real monetization beyond ads at first. Eventually, in March 2008, Zynga added a way to sell poker chips via “lead generation,” where a user could get chips if they participated in a revenue-generating activity for Zynga, such as accepting an offer to sign up for something.

In a poor choice of words that would eventually come back to haunt him, Pincus later said in his Berkeley speech that “I did every horrible thing in the book to just get revenues right away.” He said that Zynga gave users poker chips in its first game, Texas Hold ‘Em Poker, if they would download a Wiki tool that was difficult or impossible to remove.

In a poor choice of words that would eventually come back to haunt him, Pincus later said in his Berkeley speech that “I did every horrible thing in the book to just get revenues right away.” He said that Zynga gave users poker chips in its first game, Texas Hold ‘Em Poker, if they would download a Wiki tool that was difficult or impossible to remove.

In mid-2008, Zynga launched Mafia Wars, its second game, and it acquired another game called YoVille. The Mafia Wars game was available on both Facebook and MySpace, because it wasn’t clear which social network was going to be the winner yet.

In the process of launching its games, Zynga would hit upon some unique ideas that it would later describe as its philosophy. It believed games should be accessible to everyone, anywhere, any time. Games should be social. Games should be free. Games should be data driven. And games should do good. Those were lofty goals, but no one else in the industry believed in trying to make all of those things happen.

Pincus’s intent was to create a real business before he needed to go into a venture capitalist’s office. By the time Zynga raised its first round of money, it had generated only $693,000 in revenue in 2007, but it had a path to growth because its user count was growing fast, and it was already profitable. As a result, Pincus was able to command unusual terms, like giving himself stock that had 10 times the votes of common shares and maintaining control of his board of directors.

He was also able to secure investors that he was already friends with. In a deal announced Jan. 15, 2008, Zynga was able to raise $5 million from Union Square Ventures, Foundry Group, Avalon Ventures, Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel and other angels.

With the new money, Zynga was able to move even faster at a time when the great Facebook land rush was under way. The social network constantly revamped its platform and app makers had to adjust in real-time. Pincus called this “organic development,” where the company’s own internal developers had to pay close attention to Facebook and redo their work every 90 days or so.

The business would be metric-driven, combining intuition and data. The would enable the business to rapidly iterate and drive reach, retention and revenue. That is exactly how Zynga put distance between itself and others; it learned what users wanted and modified its games quickly, sometimes overnight, to better provide what the users wanted. Zynga started testing every idea. Web 2.0 companies behaved in this fashion, but game companies for the most part didn’t.

But it was true the company forever be at the mercy of the rules that Facebook made.

“Does it bother us that we’re a fly on Facebook’s ass?” Pincus joked in his talk. “In 2007, people laughed at me” for doing a Facebook app company. “We live and die by the changes these guys make.”

Data also could be a game designer’s enemy. If a game didn’t take off, Pincus had no qualms about killing it. He spent $3 million developing an unnamed role-playing game. But the title didn’t take off in a viral way when it launched, so Pincus pulled the plug on it. Pincus became ruthless about canceling games that weren’t working.

Zynga was growing fast thanks to Mafia Wars and Zynga Poker, and it was making money. And Facebook was still growing like crazy.

At the time, the speed was important. Not everyone realized it, but Zynga was in a monumental race to beat others to the treasure. If it learned the most about how to make money from social games and executed the fastest, it would own the market, regardless of whether giant companies came into it later.

So just a few months after its first round, Zynga raised another, larger pile of cash.

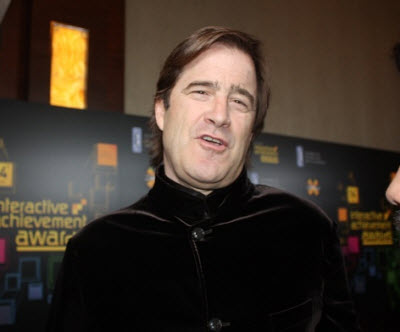

In July 2008, the world took notice as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers invested $29 million in Zynga. Bing Gordon (pictured above), the former chief creative officer at Electronic Arts and now a partner at Kleiner, joined Zynga’s board. Mark Pincus welcomed him as a key advisor.

The amount of money was huge for a gaming startup at the time. Few other companies had amassed such a large amount. It meant that Zynga was always going to have a pile of money to invest in its next major titles. That was a luxury that many of its competitors didn’t have, and it was why they fell behind.

Later on, Pincus said that one of the lessons of failure was to surround himself with people that he could learn from. Gordon was such a mentor. While Pincus had the Web 2.0 experience, Gordon knew games. He was able to put Pincus in touch with large number of job candidates in the game industry who were willing to try something new. Some of them, like veteran game designer Mark Skaggs, came from Electronic Arts. He joined as a top game exec at Zynga in November 2008. Skaggs would go on to lead some of the most important games that the company would create.

“I’m a consigliere,” Gordon said in an interview with VentureBeat in the fall of 2010, referring to the Robert Duvall character in The Godfather movie. “I have my own assignments now and then. I have done more recruiting than Robert Duvall. But I have high regard for Mark Pincus as a visionary. He combined the best of the web, games, and social. It never occurred to anyone those would come together.”

Gordon showed up at the company all of the time, lending his advice and bringing in new people as they were needed.