Finding a replacement

Zynga became a place of rapid advancement, with a chance to get promotions at an unbelievable pace. One of Mark Pincus’s rules was that employees should try to find their own replacements. The rule applied even to him.

Zynga had a number of possible successors to Pincus over the years. Bing Gordon gave him advice, but there were operations chiefs such as Vishal Makhijani. Owen Van Natta, the former CEO of MySpace and an angel investor in Zynga, joined the company in early 2010. He was an executive vice president in charge of running revenue strategy, corporate development, international expansion and brand.

But on June 3, 2011, Zynga hired John Schappert, the former No. 2 executive at Electronic Arts, as chief operating officer. Schappert’s move signaled loud and clear, like his predecessor John Pleasants’ move to join Playdom in 2009, that social and casual games were a giant wave in video games. And the veterans of the industry were now more than willing to surf on the leading edge of that wave.

Schappert had a long history at EA, starting as a game programmer and founder of the Tiburon game studio in 1994. His team made Madden NFL sports games for EA and EA bought Tiburon in 1994. Schappert rose through the ranks to take the No. 2 job, but jumped ship in 2007 to join Microsoft as head of its Xbox Live online gaming business. He rejoined EA as Pleasants — who EA made clear was asked to leave — departed for Playdom. At EA, Schappert helped steer the company’s expansion into digital games, in competition with Zynga. That business was on track to generate $833 million in digital game revenues for EA in the year ending March 31, 2012.

At Zynga, Pincus had finally found his future replacement and also brought aboard an executive that investors would have faith in as an expert in the video game industry. Van Natta became chief business officer and was eventually moved out of his executive job at Zynga. He stayed on as a board member, but seemed redundant after Schappert came on board.

Clearly, the hand of Bing Gordon, Zynga’s “consigliere,” seemed apparent in the recruitment. Schappert’s job was to bring order to the house, which had been expanding at a rate of an acquisition per month. He also had to preside over a rapid expansion of game launches as those teams started finishing games they had started under Zynga’s ownership. Schappert brought more game cred to Zynga, and that meant he was good for a potential IPO. Those potential investors who weren’t comfortable with Pincus were likely to be very comfortable with Schappert. And while there was a delay between the announcement of Schappert’s departure and his arrival at Zynga, EA didn’t sue Zynga for hiring Schappert.

Schappert’s hiring was marked by a couple of other events that signaled Zynga’s maturity. The company sued Vostu, a leader in social games in Brazil, for copying Zynga games. And Zynga also launched Empires & Allies, the company’s first combat social game made by for EA veterans who created the Command & Conquer series. Empires & Allies grew quickly and it filled another genre in the cartoon-oriented social game market that Zynga was starting to cover from all angles. Soon, other games like Pioneer Trail and Adventure World would arrive. It seemed that everything necessary for a good initial public offering had fallen into place.

The EA empire strikes back

During the summer, Zynga was courting a big prize. PopCap Games, the maker of outstanding casual game titles such as Bejeweled and Plants vs Zombies, was openly exploring its own initial public offering. PopCap’s employees had waited a long time for some kind of payoff, and it was finally coming near. Zynga wanted to buy PopCap and it was willing to part with almost all of its cash — or at least take out a huge line of credit — to do the deal.

Asked what he thought of Zynga’s purported value, PopCap CEO Dave Roberts told VentureBeat, “One has to be careful about believing valuations based on the secondary market. I am not saying Zynga is not valuable. I think it is a very valuable company. Nobody believes that that really is an appropriate market evaluation. And likewise you have to be careful when small pieces of equity are raised by companies. If Microsoft invests $50 million in something, they don’t care about the valuation because it’s a small amount of money to them. That doesn’t mean the rest of that company is worth a lot. I don’t think we’ll ever know Zynga’s true value until it is public. The same is true for PopCap.”

Then, on July 12, EA snatched PopCap away. It agreed to pay $750 million in cash and stock, as well as a potential bonus of $550 million if goals were met.

The New York Times said that Pincus reportedly offered PopCap Games a total of $950 million in cash to buy the Seattle-based casual game maker. But after hearing about the company’s history of “clawbacks,” or rescinding share awards, and fierce internal fights, PopCap decided against it. Instead, the company agreed to take a $750 million offer in cash and stock (plus a $550 million possible bonus) from EA, the Times said.

That explanation was an odd one, given the rescinding of share awards was a story that broke in November 2011, many months after the PopCap deal was announced. And on its face, the offer from EA looked a lot more attractive than Zynga’s offer. Still, when EA snared PopCap and Zynga didn’t, it started to make people wonder. Why wouldn’t a company like PopCap want to hitch its fate to a winner like Zynga? Was there something under the hood that didn’t look right? Pincus had indeed taken back stock options from some early Zynga employees.

The Times also said that three unnamed sources said that Rovio, the maker of Angry Birds, walked away from a Zynga acquisition offer worth $2.25 billion in cash and stock. Rovio made it clear that it wanted to go public. Zynga had been painted as walking on water. Was it now falling back down to Earth?

PopCap cofounder John Vechey said in an interview with VentureBeat that Electronic Arts felt like a great match because John Riccitiello, CEO of Electronic Arts, was very knowledgeable about games and understood what PopCap was good at. Barry Cottle, head of EAi, the company’s mobile and casual game studio, said PopCap was one of the dominant companies in casual games with fast growth on both Facebook and mobile games. The company made more than $100 million in revenues a year and was growing at a 30 percent rate. Sales of Bejeweled made up about 40 percent of its revenues, and about 20 percent came from Plants vs Zombies, PopCap chief executive Dave Roberts told VentureBeat. But the company was born in 2000, long before the era of social gaming. If there were any justice in the world, PopCap should have been in a position to buy Zynga.

Almost on cue, just as Zynga seemed to lock up the Facebook market, it took a broadside from EA. Almost as revenge for stealing Schappert, EA launched its life simulation game on Aug. 9, 2011.

EA had the massive franchise of The Sims, which had sold more than 140 million copies on the PC and the consoles, to fuel the growth of The Sims Social on Facebook. The game was the first massive hit from Playfish, the social game company that EA bought for at least $300 million in 2009. It was a surprise comeback, given Zynga’s dominance on the social network.

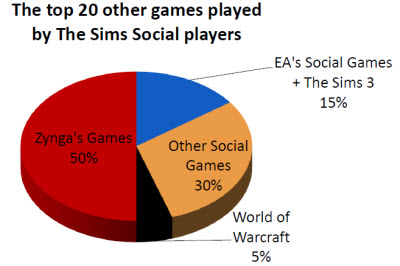

Raptr, the social network for gamers, revealed that an analysis of its 10 million users that many of The Sims Social users — millions upon millions of them — had come from Zynga. EA’s own social games and The Sims 3 accounted for only 15 percent of the total players of The Sims Social. Zynga players, on the other hand, account for 50 percent of all of The Sims Social players.

Raptr, the social network for gamers, revealed that an analysis of its 10 million users that many of The Sims Social users — millions upon millions of them — had come from Zynga. EA’s own social games and The Sims 3 accounted for only 15 percent of the total players of The Sims Social. Zynga players, on the other hand, account for 50 percent of all of The Sims Social players.

On Sept. 12, the Sims Social’s numbers exceeded FarmVille’s. By Oct. 12, The Sims Social became the No. 2 game on Facebook with 66 million monthly active players, compared to 76 million for CityVille, according to AppData. If roughly half of those players came from Zynga, that was about 33 million users who had defected. Of course, not every single one of the Zynga players quit playing a Zynga game in order to play The Sims Social. But CityVille dropped from more than 100 million players.

EA’s success reminded everybody about what Zynga itself acknowledged as a risk factor in its IPO filing: The barriers to entry are low in social games, and the competition is intense.

“The Sims Social proved they can bleed, and if they can bleed, we can kill them,” said Jeff Brown, vice president of corporation communications at EA, laughing.

But by the end of its run, it was clear that The Sims Social wasn’t going to catch CityVille. The rate of growth fell off and, with extra marketing spending by Zynga, CityVille started to grow again.