The first mover advantage

Rivals like Slide and RockYou rose to the top with lightweight apps such as tossing sheep or sending gifts to friends. In 2008, Social Gaming Network, or SGN, emerged as a rival maker of casual games on Facebook. In the early days, any one of these companies could have become what Zynga is today: a Facebook gaming juggernaut. But they didn’t seize the opportunity at the right time, and they didn’t have the vision. Pincus, on the other hand, repeatedly said, “We were the biggest macro bet on social gaming.”

Pincus moved fast. He went through a lot of employees, getting rid of poor performers. Many left because they either didn’t like Pincus or because the company moved too fast for them. Pincus was results-oriented.

While Gordon had shown his faith, many people weren’t believers. Zynga had made $19.4 million in revenues in 2008, but its financials were secret. The secrecy was a good thing too, since Zynga lost $22.1 million for the year. But Pincus wasn’t deterred. At the first GamesBeat conference in March 2009, he declared that social gaming wasn’t a fad. He said that Zynga was signing up 700,000 to 800,000 new users a day.

“I believe that social gaming is something that will reach over to a mass audience that [most gaming] has not,” Pincus said. “I believe that social gaming is a new medium.”

Pincus told Andrew Cleland, a partner at Time Warner Ventures (and later Comcast Ventures), that Zynga would be more valuable than Electronic Arts in five years. Back then, that statement was laughable, as EA was a multibillion-dollar company.

By April 2009, Zynga had 40 million monthly active users and its poker game was the top title on Facebook. The game was the first one to reach more than 10 million monthly active users.

In May 2009, Pincus summarized his experience so far. He said Web 1.0 was about aggregating audiences, or getting page views, and banner ads and e-commerce ruled. Web 2.0 was the search economy which enabled many more businesses to participate through search engine optimization. Web 3.0, he said, was about monetizing a massive audience through users paying for virtual goods and services.

In May 2009, Pincus summarized his experience so far. He said Web 1.0 was about aggregating audiences, or getting page views, and banner ads and e-commerce ruled. Web 2.0 was the search economy which enabled many more businesses to participate through search engine optimization. Web 3.0, he said, was about monetizing a massive audience through users paying for virtual goods and services.

While virtual goods were a bit of an experiment for U.S. gamers in 2007, Zynga would eventually realize that it had hit upon a real business model. Its apps were free, but users could purchase virtual goods with real money. At a time when ad revenues and paid subscriptions were weakening with the poor economy, the free-to-play model looked like a winner. Virtual goods would later become 95 percent of Zynga’s revenue stream.

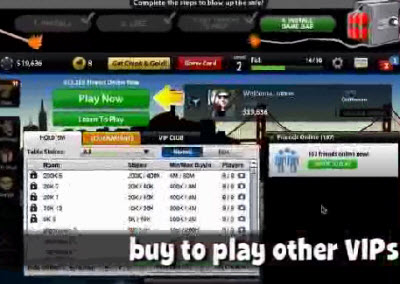

They paid for Zynga’s virtual currency, poker chips, so they could keep playing in social games with their friends. For $5 a month, poker players could become VIPs. The social part was something new to gaming, particularly casual players on Facebook, and it was addictive. Only about 2.5 percent of the users paid for something, but that was enough to make the whole enterprise profitable, since the cost off adding users was getting cheaper and cheaper with more efficient internet infrastructure. Much of Zynga’s expertise was in figuring out how to create a funnel that made players into payers.

Zynga learned one of the great benefits of the free-to-play model. There was no upper limit to what some users would pay, just as you could put as many quarters as you wanted into the old arcades. With $60 console games, game publishers had set their upper limits on revenue per user. But Zynga sold poker chips in packages of $5, $20 and later $100.

“You know what, there are people in Kuwait who will pay $100 for chip packages,” he said. “In this user-pay economy, too many people mis-price their stuff at $2 in micro-transactions.”

Zynga’s games also didn’t require a huge budget. Console games required tens of millions of dollars because they had such sophisticated 3D graphics and required teams of 100 people or more. Zynga could get by with a fraction of such team sizes, with development lasting for a matter of weeks. Game budgets were in the low millions — at the highest.

Zynga’s games also didn’t require a huge budget. Console games required tens of millions of dollars because they had such sophisticated 3D graphics and required teams of 100 people or more. Zynga could get by with a fraction of such team sizes, with development lasting for a matter of weeks. Game budgets were in the low millions — at the highest.

When Facebook’s audience was young college students, dating apps and other light fare ruled. But as the social network grew, it added older users who were more a reflection of the general population. Many of these were not gamers and would never pick up a controller for a game console, but they didn’t mind playing a game for a few minutes a day with an old friend. Some of these users had finally become comfortable paying for things that existed only in a digital universe.

One of the big problems with virtual goods model soon became clear: the potential for massive fraud. Some users would try to hack the system and defraud Zynga, stealing virtual currency and virtual goods. PayPal, Pincus said in 2009, “sucks ass” when it came to detecting fraud from first-time transaction users.

The first time that Zynga turned on its payment systems in 2008, it got hit with a huge amount of fraud within 48 hours. It almost killed the company because, if 2 percent or more of the transactions are fraudulent, payment processors may drop a company. Zynga had to go to payment processors of the last resort: those who serviced the porn industry. Zynga had to get good at that, but it took 90 days before the charge-back rates were fully accounted for. Soon enough, Zynga got the charge-back rates down to half a percent.

With the fraud under control, Zynga was able to expand to new games like Mafia Wars and YoVille.

The clone wars

The clone wars

Zynga released Mafia Wars in April 2008. It was a simple text-based role-playing game where you could team up with your friends in a mob and order hits on your enemies.

The problem was that it was almost a pure clone of another game, Mob Wars. Dave Maestri, who created Mob Wars for Freewebs.com, sued Zynga in February 2009, alleging copyright infringement. Zynga had tried to ward off the suit by making changes to its game. But Maestri, who was now at Psycho Monkey and was enmeshed in his own legal tangle with former employer SGN to get the rights to Mob Wars, sued anyway.

Most game companies copy the ideas of their predecessors, and mob games were hardly new. Copying was an outright epidemic, particularly among game executives who were afraid to bet a lot of money on original ideas and preferred to stick with known game genres, from fighting games to role-playing games. It was easier and largely legal to rip off your competitor.

The Mob Wars suit alleged that Zynga crossed the line by copying exact features. The games had similar characters, place names, currency, experience points for crime jobs, and other features.

But the copying accusations cut both ways. Tom Bollich, a former Zynga employee, said that Maestri was about to sell Mob Wars to Zynga. But as the acquisition talks were wrapping up, Maestri attended a lecture by the company on how to monetize games. Maestri learned from Zynga how to make money on his own, added that to his game, and no longer had to sell out.

“The deal was almost completely done,” Bollich recalled in an interview with the SF Weekly. “Dave was there, learned everything, cancelled the deal, and then put all our suggestions in his game the next week, and started making money.”

It didn’t help Zynga’s case that Pincus was fairly honest about the larger copycat problems in the game industry. Early on, Pincus said he liked competitors like Playfish that did research and development and expanded the industry.

“We learn from them,” he said.

In an interview with VentureBeat in 2009, Pincus said, “You can look at why did our Mafia Wars beat Mob Wars. Mafia Wars came out nine months later. We had 40 people on it. We would add features four or five times a week. Others competing with us were more cottage businesses and didn’t invest as much.”

In one of the most damaging articles against Zynga, the SF Weekly wrote in a popular article entitled “FarmVillains” that Pincus regularly ordered his game creators to copy the work of their rivals. If his games succeeded better than the earlier ones, it was because Zynga knew how to spam Facebook users with game messages and advertise its games in the right places.

“I don’t f****** want innovation,” an ex-employee quoted in the SF Weekly recalled Pincus saying. “You’re not smarter than your competitor. Just copy what they do and do it until you get their numbers.”

“I don’t f****** want innovation,” an ex-employee quoted in the SF Weekly recalled Pincus saying. “You’re not smarter than your competitor. Just copy what they do and do it until you get their numbers.”

Articles like this one and the obvious similarity of Zynga’s games to others didn’t win it any friends in the traditional video game industry. When Zynga employee Bill Mooney accepted an award at the Game Developers Conference, he was roundly booed. Even though the practice of copying was rampant in console games, developers in that world had a more refined sense of their mission. They were creating works of art, building on the shoulders of great artists like Leonardo Da Vinci. And here Zynga was, creating games that copied others and were more like trivial slot machines than real games.

Ian Bogost, a game design professor Georgia Institute of Technology and founding partner of Persuasive Games, criticized Zynga for “strip mining” behavior, or creating games that tricked users out of their money and gave “no care about the longevity of the form or the experience.”

Many in the industry felt that Zynga’s approach to games was destroying the culture and artistry that the industry had worked so hard to achieve as it tried to find its place among books, movies and music as a legitimate art form. Zynga was also destroying the hardcore industry itself, offering free games as the console companies tried to sell their titles for $60 a piece. On that front, Pincus had no sympathy for tradition.

Fair or not, Zynga’s reputation in the early days was one of being a clonemaker. If game developers went to work there, others felt it was part of some kind of get-rich quick scheme, as it seemed like Pincus was probably going to build his company fast and flip it in an acquisition. They were sellouts. And the perception that Zynga wasn’t a game company and wasn’t making real games started with the fact that Pincus had no roots in games.

Those who viewed Zynga in that fashion were clearly underestimating it. Pincus was also on his fourth company and he had arranged the ownership so that he alone would be the one to choose whether Zynga was sold or not. The venture capital investors — who often were the cause of early exits — had no ability to force a quick sale.

True or not, the early negative reputation made it harder for Zynga to attract game developers. In an interview with VentureBeat in September 2010, Gordon said, “‘Copycat’ is a loaded term. At Electronic Arts, we had some studios that were better at simulations or sports. They reduced the development time and risk if they focused on what they were good at. You could put a picture of what you wanted to accomplish on the wall, with a bullseye on it. You would say we are going to beat that, and that saves you a lot of time. At EA, we wanted to do games that were one-third new, one-third old, and one-third improved.”

Gordon added, “It’s like taking writing classes and looking at artists in college. I would try to write in a style of someone who came before me. You imitate before you innovate.”