Recruiting talent

During this time, everything was moving fast. As Zynga expanded, it was able to bring on game talent in part because there was a recession that was killing off a lot of console game studios. Bing Gordon’s presence on the board of Zynga — and his regular presence at the company — gave the company better credibility.

Gordon knew what Zynga’s reputation was like and he tried hard to contain some of that damage. According to papers obtained by the SF Weekly, Gordon wrote a confidential memo to his partners at Kleiner Perkins.

It said, “Mark needs strong lieutenants to keep him from micromanaging.” Gordon suggested that he and another top executive play strong roles in the company to offset Pincus’s style. “Bing to temper Mark, and bring on board a billion-dollar game industry COO when Zynga gets to about $100 million.” The memo also warned that Zynga was overly reliant on Facebook.

But Pincus lasted far longer than anyone thought, given that he was running a game company. And he did so by finding talent wherever he could. He didn’t wait for the game developers to come to him.

Sometimes, Pincus found technical experts and asked them to become game makers. Justin Cinicolo, a mid-20s Carnegie Mellon University grad with a few years of work experience, decided to check out Zynga because his roommate got a job there and was coming home with a smile on his face. Cinicolo also joined early and was so thrilled at the fast pace and energy that he recruited another dozen Carnegie Mellon friends to join.

What Cinicolo found was that Zynga tried to live up to what it would later codify as core values. The company told its people to “build the games you and your friends love to play,” “Zynga is a meritocracy,” “Be a CEO and own outcomes,” “Move at Zynga speed,” “Put Zynga first, decisions for the greater good,” and “Always innovate.” Some might find that laughable, but Cinicolo could see the truth in it.

The idea of being a CEO resonated with Cinicolo, and it came from Pincus himself. Pincus recalled that, at his second company, he put some sheets on a wall and wrote everyone’s name on it. “By the end of the week, everyone needs to write what you’re CEO of, and it needs to be something really meaningful…. People liked it. And there was nowhere to hide,” Pincus said.

Cinicolo was installed as a producer on Mafia Wars after the game launched. His job was to keep it growing and to beat its competition.

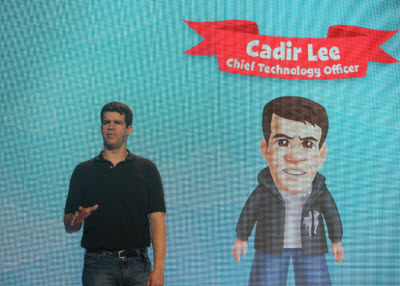

In analyzing the game, he had to rely on tools from Cadir Lee, who had co-founded two other companies with Pincus and had joined Zynga when it had around 100 employees, in November 2008. At the time, Lee’s mission was to build the greatest data warehouse in the entire game industry.

Lee’s first job was to build a dashboard for analytics, taking it from a bunch of numbers to a user interface that could show producers like Cinicolo everything they needed to know about a game. They could do A/B testing, or test to see if gamers like a pink message better than a blue message. When the results came back, it was easy to decide which worked better and the company could learn such lessons at an extremely fast pace.

“We built analytics from zero to a competitive differentiator,” Lee said in an interview with VentureBeat in the fall of 2010. “We have a mass of infrastructure, analysis, and statisticians. It is the lifeblood of Zynga.”

Benjamin Joffe, chief executive of social game maker Cmune, said that Zynga made analytics into a science and operated on the principle of “do more of what works.”

That was another thing that traditional game developers hated. They wanted to design their games by intuition and craftsmanship, not popular vote. But some of them saw the logic of it. Normally, developers would work for two to five years on a console game and then find out on launch day if the gamers really liked it. With Zynga, a developer could create code that millions of players would see the next day. The feedback was immediate.

With analytics tools, it was a lot easier for Cinicolo to take the Mafia Wars game and boost it. Four months after it launched, it had around 100,000 users. Cinicolo’s goal was to boost it to a million. When he hit that, his boss Eric Shiermeyer asked him to take it to 2 million. In 2008, Mafia Wars generated 20 percent of Zynga’s revenue. The next year, Mafia Wars grew dramatically and it contributed $32 million in revenue in 2009 and $161 million in revenue in 2010. Mafia Wars still has about 6 million monthly active users.

“I went from project to project, with a ragtag group,” Cinicolo said in an interview in the fall of 2010. “I was creatively very energized. If stuff breaks, we fix it.”

Depending on the project, Cinicolo worked with Mark Pincus on a weekly or a daily basis, soliciting ideas from his boss on how to make the games better. The team would stick around for free dinners and drink beer as they talked about where to go next. By 2010, he transferred over to the mobile game frontier.

“Pincus acts like a partner,” Cinicolo said. “He’s never really a boss. He collaborates. In some ways, he has changed. He has gotten calmer. He is super-energetic and as passionate as ever. But he is more willing to do things like mobile where we know it will take some time before it becomes as successful as the web business.”

At age 28, in the fall of 2010, Cinicolo was in charge of a number of major mobile game efforts as general manager of mobility.

By the end of 2008, Maestri settled his lawsuit with SGN and won the rights to Mob Wars. Then, in September 2009, he settled with Zynga, which agreed to pay him $7 million to $9 million. By that time, Zynga had its own bone to pick with Playdom, which Zynga accused of hiring its employees in order to copy its games and steal its “playbook” for making popular games.

The making of FarmVille

The making of FarmVille

In the spring of 2009, a small developer called Slashkey created a game called Farm Town. It was a simple farming game, not much different from farm games in China or the old Harvest Moon games on the consoles. All it did was enable users to simulate the life and growth of a farm. With only viral word-of-mouth for marketing, the game spread like wildfire, adding 300,000 users a day. Within a matter of a couple of months, it had more than 14 million registered users on Facebook.

It seemed like FarmVille was an obvious copycat, but the game’s origins are a little murky. Mark Skaggs, the former Electronic Arts game designer at Zynga, said the idea for a new title came from Bing Gordon, the Kleiner Perkins partner and Zynga board member. One day, he put his feet up on the desk and asked, “Why don’t you make a farm game?” It was a sentiment that Mark Pincus shared.

Skaggs was one of the instrumental early game designers at Zynga. He had been in charge of a variety of PC games that had sold more than 16 million copies at Electronic Arts, from Command and Conquer Generals to Lord of the Rings Battle for Middle-Earth. He spent seven years at EA, after the 1998 acquisition of Westwood Studios. He left EA in 2005 to co-found Trilogy Studios, which was making a massively multiplayer online game. That didn’t work out, so Bing Gordon suggested that he give Zynga a try. He joined early enough to have a lot of influence with the way Zynga designed its games.

Unfortunately, Zynga didn’t have a full team available. Skaggs had to look on the outside. Zynga was in talks to buy MyMiniLife, which had a few employees and a game engine that could be used for the farm game. Between Zynga and MyMiniLife, the team grew to nine people. They worked for five weeks to get the job done. Some of that work was done before Zynga had acquired MyMiniLife, which included Sizhao Yang, Amitt Mahajan, Luke Rajlich, and Joel Poloney.

MyMiniLife was started in 2007 as a social network and it grew to 4 million users. The company was working on a game engine for running Flash-based games on a social network. This was a tough thing to do, as Flash games could run notoriously slow, particularly if they weren’t customized properly. The engine was working well enough that it could be easily modified to run different games.

But MyMiniLife struggled to retain users. Max Levchin of Slide made the first acquisition offer, followed by Zynga, Hi5 and Challenge Games. Zynga wined and dined the team and kept raising the bid. Mark Pincus spent a lot of time working on the deal, which was closed on June 5, 2009 for an undisclosed price. It was one of those times when Pincus had acted very decisively on just a little bit of information. He used his instincts and drove his team in the right direction to get the deal done.

MyMiniLife had built a stable platform that could handle lots of users. Without it, scaling would have been an issue.

The production team moved so fast that they stole the avatars, or virtual characters, from Zynga’s YoVille game. Mothers using Facebook to monitor their kids’ activities or stay in touch with old friends were the primary target. Besides Skaggs and the MyMiniLife team, others who worked on FarmVille included Raymond Holmes, Sifang Lu, David Gray, and Craig Woida.

On June 19, 2009, Zynga launched its Farm Town clone, FarmVille. With the a production cycle of only five weeks, the game grew at an unprecedented rate. Unlike its rivals, Zynga started spending lots of money on ads on social networks. Within two months, Zynga’s FarmVille had 5 million users. Pincus pulled resources from other projects to support FarmVille’s growth.

Meanwhile, Farm Town was hitting growth pains. By contrast, Zynga hit a million players within four or five days. It already had millions of users and was tapping the outside computer services of Amazon, whose Amazon Web Services division was farming out data centers that the company didn’t need for its core electronic commerce business.

All of that computing power gave Zynga a lot of insight. Cadir Lee, chief technology officer, said in an interview in the fall of 2010 that Zynga could mine its data because it was a web company.

“We get data within 5 minutes of something happening,” he said. “Metrics and watching data is a part of the culture. Web companies do a lot of analysis. You have this virtual world where you track everything that happens, like how many plots of super berries there are.”

Asked if FarmVille beat Farm Town because of Zynga’s better web infrastructure, Lee said, “That’s a fair representation.”

With Amazon, Zynga was about to scale its web servers up or down as it needed. It was much more prepared for hyper growth with a game than a smaller rival such as Slashkey.

“We solved a lot of tech problems for FarmVille,” Lee said. “We had some days where servers were on the edge of blowing up and we would release a new technology that gave us more head room. We learned what scaled way, and later on we would really shift the way we built our games. We found it was not the amount of hardware that mattered. It was the architecture of the application. We had to build it in a way that took advantage of Amazon.”

The MyMiniLife engine proved to be a competitive differentiator and it was used again in every Zynga game from FrontierVille on. It was one of the secrets behind Zynga’s success, as other companies made Flash-based games that took to long to load or just ran unacceptably slow.

Once again, traditional game designers looked down on Zynga’s “game.”

Ian Bogost, the Georgia Tech professor, was so disgusted with FarmVille’s lack of game play that he created a parody called “Cow Clicker,” where all you did was click on cows. It would take a long time for Zynga to escape that kind of criticism.

By July 2009, the world was catching on to Zynga’s fast growth. On July 31, 2009, comScore reported that Zynga had become the No. 1 online game operator in the U.S., surpassing Yahoo Games with a total of 44 million monthly unique users. Pincus said that estimates that Zynga would generate more than $100 million in revenues in 2009 were “conservative.”

The free-to-play business model was working. Within a few months FarmVille had become the biggest online game in the world and a small percentage of users were buying enough games to make it profitable.

The free-to-play business model was working. Within a few months FarmVille had become the biggest online game in the world and a small percentage of users were buying enough games to make it profitable.

Zynga beat out the rivals because of execution. One of its smartest features was “wither,” which aged your crops over time so that they became worthless if you didn’t harvest them soon enough. That kept users coming back to the game often; and Zynga sold “unwither” to revive withered crops. That was one reason why the game monetized well.

In an interview with VentureBeat in 2009, Pincus said:

Look at Farm Town. Something happens around 3 million daily active users. You hit ceilings. You have to be a real company with customer support, deal with fraud and payments, and all of those things force you to decide if you will double down and make an investment for the long-term. Your management hassle goes up and you have a lot of employees. At the beginning, we knew who we wanted to be as a long-term company. There was no question we would be a long-term company.

In September 2009, Zynga launched Cafe World, a restaurant-building game. It was a pretty clear attempt to duplicate the success of Restaurant City, a Facebook game that launched in April 2009. Headed by general manager Roy Sehgal, the game became Zynga’s fastest-growing game to date. Seghal said in an interview with VentureBeat that the Clubhouse Studio team consisted of 25 producers, product managers, game designers, artists and programmers. They were all from a variety of backgrounds, not just games, and they worked on the title for about five months. Not everyone had worked on a game before.

Soon enough, Zynga’s Cafe World game had 28 million monthly active users, while Restaurant City had 16 million. It was like FarmVille versus Farm Town all over again.

Since Zynga raised more money than its rivals, it could afford to advertise, but not in an outlandish way. Still, the stakes were getting higher. Ad network operators such as RockYou were getting a dollar per installation of a game. That meant that other developers would pay $1 for every user that RockYou convinced to try out a game on Facebook. Over time, the cost of advertising on Facebook rose, and many startups couldn’t keep up. It was starting to look uneconomical for them to do anything but sell out to another rival, like Zynga.

By the fall of 2009, Pincus was looking like a prophet. At the Web 2.0 Summit, he predicted the future would be based on an “app economy.” The company had more than 50 million users, including 20 million FarmVille users. Zynga was selling something like 800,000 virtual tractors a day. All of that was happening amid the greatest financial collapse in modern times. That financial collapse was weakening all of Zynga’s competitors.