Gold Rush or bubble?

In January 2011, Zynga privately obtained a valuation of its company. The third party evaluation firm said that Zynga was now worth $4.98 billion. As the economy improved and the value of both Facebook and Groupon kept going up. Zynga also benefited from a period of froth, as investors were looking for a way to cash in on the Facebook phenomenon. Only a few investors could actually invest in Facebook, but the demand for shares was rising.

On Feb. 13, 2011, the Wall Street Journal reported that Zynga was raising $250 million in a round of funding that valued the company at $7 billion to $9 billion. It was a lot more than the secondary market valuation of $5 billion and it showed that investors were still excited about investing in social games and anything related to Facebook. At the time, Zynga was still riding high on CityVille and it had 275.8 million monthly active users.

EA’s value was around $6 billion. The comparison between the valuations was crazy. EA’s projected revenue for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2011, was expected to be as high as $3.7 billion (non-GAAP). For calendar 2010, Activision Blizzard’s revenues were $4.8 billion (non-GAAP). EA and Activision both had more than 7,000 employees. Both were profitable on a non-GAAP basis.

Everyone had an inflated belief about Zynga’s value. Zynga’s revenues in 2010 were estimated to be $850 million, with a profit of $400 million, according to confidential sources cited in the Wall Street Journal. (Actual revenues, revealed later in Zynga’s IPO filings, were $597 million and net income was $90 million). The company had more than 1,500 employees and it had been buying a game studio once a month. By comparison, EA said it was on track to hit digital revenues of $750 million in the fiscal year that ends March 31.

Back in October, Zynga’s value was a mere $5.27 billion, according to limited trading on secondary markets, where employees and other shareholders were allowed to sell their stock to well-heeled investors. At that point, its value surpassed EA’s. Bubble-conscious observers asked: what did Zynga do to double its market value in a little more than three months?

Zynga was trading at more than 11 times 2010 revenue. Activision Blizzard was trading at around 2.7 times 2010 revenue, and EA was somewhere around 1.7 times revenue. Zynga was most likely being valued on the basis of its potential revenues and earnings; since it was growing at a faster rate, investors were naturally going to value it higher. And Zynga was clearly part of the rarefied social media technology club that also includes Facebook, whose value soared to $50 billion in a recent funding; Groupon, valued at more than $6 billion; LinkedIn, which is preparing to go public; and Twitter, valued at $8 billion to $10 billion.

Zynga attracted enormous investor interest since it cracked the free-to-play gaming model, where the games are free but players pay for virtual goods. Asian game companies had done that as well and it was worth noting that Tencent’s value was around $46 billion on the Chinese stock market. Most of China’s online game companies, however, were valued at under $4 billion.

People could argue that Zynga’s value isn’t real, since it was in the midst of an investment bubble, and it is bound to deflate. But traditional game companies had to realize that Zynga could use its valuation to buy assets with real value. Zynga was buying a small game studio every month, but it had built enough of a cash hoard to buy a traditional game maker. It could invest enough money in new games where it would become a threat to be reckoned with. That was how bubble value could turn into real value.

Lots of big game brands were going to attack Zynga’s core market of Facebook games during 2011. But it was likely going be very hard to dislodge Zynga, which had moved into a kind of self-perpetuating state. Zynga had to spend a lot of money on marketing to stay there, but as long as it had the cash, and could get more of it, Zynga was very formidable on Facebook. Zynga could also point to mobile as the next great market for expansion.

At the time, no one got the details on Zynga’s investment round exactly right. But Zynga later said that it raised $490 million in February. The large round served Zynga’s purposes of postponing an IPO until it could accomplish goals such as regular profitability, diversification beyond Facebook, mobile expansion, and international expansion. All of those goals would help Zynga produce earnings that could keep investors from getting spooked. Previously, Zynga had raised around $360 million, so the new round gave Zynga more cash than the company had raised to date.

By March, Zynga’s valuation was $10 billion. By late May, Zynga’s valuation was determined to be $13.98 billion. At that point, rumors that Zynga would go public started building. Some backlash had begun to build that no company could create value at such a rate, and that this was part of another Silicon Valley bubble.

Recognition at last

At the Dice Summit in 2011, 700 game designers and other elite members of the industry listened to an opening discussion about how games such as FarmVille and Angry Birds were disrupting the traditional game industry. Zynga was represented by Bruce Shelley, a famous game designer who had created titles such as Age of Empires and was now a consultant for Zynga.

Mike Morhaime, head of Blizzard Entertainment, said he plays Words With Friends, a Scrabble-like word game on the iPhone, so that he can connect with old friends.

Mike Morhaime, head of Blizzard Entertainment, said he plays Words With Friends, a Scrabble-like word game on the iPhone, so that he can connect with old friends.

Greg Zeschuk, co-founder of Electronic Arts’ BioWare division, said he pulled someone into his office to show off CityVille on Facebook. “Come take a look at the future of games,” he said. He said game designers can now reach so many users so fast with games that are accessible and easy to play. At the time, CityVille had around 100 million users.

“We have never had a chance to reach so many people so fast with something so easy to play,” Zeschuk said.

Bruce Shelley, co-founder of the now-defunct Ensemble Studios and maker of Age of Empires, was so enthralled with Zynga’s FrontierVille (made by his friend and game veteran Brian Reynolds) that he decided to start work on Facebook games himself.

“This [game] had engagement,” said Shelley. “It was a real game. It meant that game design had been brought to a new space where it had never reached before.”

At the summit, Bing Gordon received one of the highest honors in the video game industry. He received the lifetime achievement award from the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences for his work in the game industry over 25-plus years. Gordon was an early employee and chief creative officer at Electronic Arts. He could have retired after his 25 years at EA. But as a partner at Kleiner Perkins, he had scored big. He had funded both Ngmoco, the mobile game company that was sold for $403 million, and Zynga. Gordon’s award was not only recognition of his past, but also his current successes. And that meant that Zynga, Mark Pincus, and social games now had a place in the game industry.

Rich Hilleman, chief creative director at Electronic Arts, said that Bing’s comments often have to be translated from “Binglish.” But Hilleman, game designer Will Wright, and others said that Gordon was frequently brilliant (with one of them saying, “you can’t judge a book by its cover.” In the video celebrating Bing, Mark Pincus said, “The scariest thing about Bing is that he is usually right.”

Gordon wrote a poem called the Golden Age of Gaming, which celebrated the industry’s ability to reinvent itself. Gordon thanked many of his colleagues for “giving me the chance to reinvent myself.” He added, “Twenty five years later, we are all an overnight success.” One of the gems from the poem: “Today our industry is experiencing reframing; but recognize this: we are all in the golden age of gaming.”

It certainly was a Golden Age for Bing, and for Zynga.

There was still some lingering tension and doubt. Jade Raymond, a celebrated game developer at Ubisoft, said she found it depressing that people were spending less time with the hardcore console games that her company had made. However, most game companies were furiously creating digital gaming businesses in social and mobile games. Zynga had changed the whole industry.

In a lecture the next day, Gordon told the Dice audience that Zynga was focused on the broader topic of play. As far back as 2004, Electronic Arts had noticed that its games were consuming more time than movies. EA’s Club Pogo accounted for 225 million hours of play in 2004, compared to 180 million for Madden NFL, 150 million for Halo 2, and 126 million hours for the most popular movie, Shrek 2. Gordon believed that game design was so powerful that it was going to spill beyond the borders of the game industry. He called it the “videogamification of everything.” The thinking of game designers was spreading into non-game web sites that wanted to attract more people. Social software was remaking of everything, from corporate learning to education. And while he touted Zynga’s games, he also said, “World of Warcraft is the new Tolstoy,” in a nod to hardcore games.

The audience listened to Gordon’s sometimes rambling talk, which brought together experience from both the console side and social. He was a bridge between the industries. He had helped bring Zynga a long way from its days of ridicule. Simon Carless, executive vice president of the UBM Techweb Game Group (which puts on the Game Developers Conference), said, “There’s a lot less tension than there used to be. The social developers are using more game design concepts, and their games are more fun than they used to be. And the core game developers are learning how to create more social experiences.”

Google courts Zynga with Google+

Google quietly gave Zynga more than $100 million in venture funding in a round that was never announced. One of the reasons was that Zynga didn’t want to cause an open rift with Facebook. But Google was clearly aiming at driving a wedge between the two partners as it prepared to launch its own social network. After much preparation and media speculation, Google finally unveiled Google+ on June 28, 2011. After two weeks, the service hit 10 million users; after four weeks, it hit 25 million. By October 2011, it hit 40 million users.

Google quietly gave Zynga more than $100 million in venture funding in a round that was never announced. One of the reasons was that Zynga didn’t want to cause an open rift with Facebook. But Google was clearly aiming at driving a wedge between the two partners as it prepared to launch its own social network. After much preparation and media speculation, Google finally unveiled Google+ on June 28, 2011. After two weeks, the service hit 10 million users; after four weeks, it hit 25 million. By October 2011, it hit 40 million users.

The company slowly doled out invitations so that it could add features and maintain good service. On Aug. 11, the company opened the service up to games. Vic Gundotra, senior vice president of engineering, said that the experiences that people share together are just as important as relationships, so the goal of Google+ games was to make online games as fun and meaningful as playing in real life. That meant Google was going to put a premium on social sharing in games, which would be built by third parties.

In a little jab at the spam-like nature of game notices on Facebook, Gundotra said that “Games in Google+ are there when you want them and gone when you don’t.” In other words, Google designed its game business so that it wouldn’t spam non-gamers.

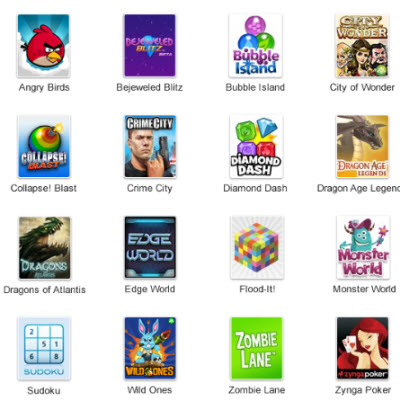

It launched 16 titles, including Zynga Poker. Once again, Zynga was trying to diversify away from Facebook. And Google looked like it was going to be a major platform that could grow as large as Facebook and even steal some users away from it.

There was a reason why Google seemed like it was in a big rush to get games up and running on its Google+ social network. That’s because games were the way that Google would put financial pressure on Facebook.

Joseph Ranzenbach, vice president of operations at PrivCo, a New York company that evaluates financial data for private companies, had some interesting analysis of the Facebook-Google fight. He said that Google+ games could badly damage a major source of revenue for Facebook.

That’s because Google started by only taking a 5 percent cut of virtual goods transactions from third-party game makers, while Facebook was taking 30 percent. If developers sell virtual goods for a game on Facebook, they have to use Facebook Credits and Facebook gets to keep 30 percent of every transaction. That has made a number of developers angry.

PrivCo calculated that roughly two-thirds of Facebook’s revenues come from advertising, while the remaining third came from Facebook Credits. So Google+ games was attacking a third of Facebook’s revenues. Of course, lots of Facebook’s ads were placed on pages where users are playing games, so a significant chunk of the ad revenue was related to games as well.

Google found a way to attack Facebook, and Zynga was an important piece of the puzzle in making it happen. In the future, Zynga might not have to fret so much about being dependent on Facebook. With Google+ around, Zynga could be a kingmaker among the social platforms.