This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Editor’s note: Spencer shares with us the lessons he learned from his first PC upgrade and playing StarCraft the proper way. The most interesting part of this piece is how he notes how the most important part of a machine isn’t mechanical. -Jason

My family owns a dishwasher that’s been broken for the past four years. We used it every day until it broke, and then we completely ignored it. We didn’t bother to fix it or get rid of it. Nowadays, it just sits there, taking up all that space in the kitchen, and we treat it like scenery. We wash our dishes by hand.

My knowledge of computers is a lot like my knowledge of dishwashers: I can change the settings and use all its marvelous features, but I’d be damned if I could fix one on my own. My computer has died before, too. One time a few years ago, the power supply short-circuited, taking out the motherboard along with it. Unlike the dishwasher, I didn’t blink an eye before getting it fixed — I can’t check my e-mail at the kitchen sink, after all.

Let’s face it: Computers blow dishwashers right out of the water. Seriously, you can’t compare them. I love my computer much more than any dishwasher for its many uses: Internet surfer, word processor, music organizer, but mainly as a gaming machine.

I’ve enjoyed playing computer games since my childhood, even when my machine could barely handle them. For years, my store-bought PC struggled to run Half-Life and CounterStrike 1.6. I wasn’t getting the gaming results I wanted, so last year I decided to upgrade my languishing desktop into a real gaming machine. I replaced power supply and motherboard after the previous damage, so all I needed was some extra RAM and a new graphics card.

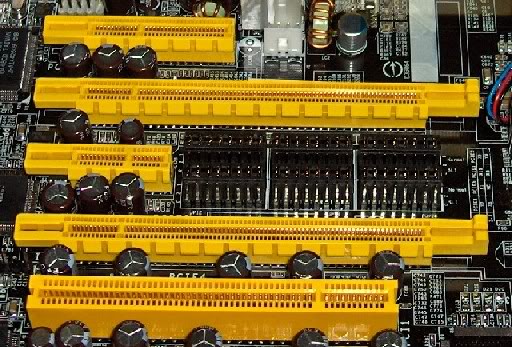

You could say I have a “romantic” view of most technology, including computers. I appreciate the surface-level conveniences, but I have no experience with the technical side. Since I wasn’t a hardware expert, I first needed to research exactly how to upgrade a computer. A message board pointed me toward an application called CPU-Z for detecting hardware specifications, which would show me what parts to buy. I ran the detection software, and it spat out the results. The program identified my processor, my memory, my motherboard, and, most importantly, the graphics port. I needed that information in order to know which kind of video card to get. After double-checking my trusted CPU-Z program, I chose a moderately priced AGP card.

You could say I have a “romantic” view of most technology, including computers. I appreciate the surface-level conveniences, but I have no experience with the technical side. Since I wasn’t a hardware expert, I first needed to research exactly how to upgrade a computer. A message board pointed me toward an application called CPU-Z for detecting hardware specifications, which would show me what parts to buy. I ran the detection software, and it spat out the results. The program identified my processor, my memory, my motherboard, and, most importantly, the graphics port. I needed that information in order to know which kind of video card to get. After double-checking my trusted CPU-Z program, I chose a moderately priced AGP card.

When the parts arrived, I was eager to install them right away. My father and I disconnected the computer and opened its metallic body. The RAM was easy to find and remove. “Like Legos,” said the Internet tutorial guy, whose video we watched before attempting the transplant. Right, like expensive Legos….

Next came the video card. Neither of us had handled such a thing before. My father and I poked and yanked at the PC’s open chest cavity for several minutes before realizing that there wasn’t a graphics card in the computer to begin with (a good reason why Half-Life lagged on my machine). We found the graphics port and carefully tried to snap the card in place. For some reason, it didn’t fit in the slot. We couldn’t understand what went wrong; we turned the card in all directions, but no configuration could match the pieces of plastic. Confused and a little discouraged, we hooked up my dishwasher of a desktop with no video improvement.

About a week later, my father and I went to Bihn, our local computer technician. He runs an electronics store in our neighborhood, and he always helps us with hardware woes. He’s the one who replaced the fried motherboard and power supply a couple years ago. We lugged the desktop and video card over to his shop and showed him the problem. He took one look at the motherboard’s graphics port and said, “That’s PCI-e, not AGP.”

I couldn’t believe it, but I should have known. We thanked Bihn for the information and returned home, ready to send back the AGP card for a PCI-e one instead. Afterward, I did a little more research and found my mistake: I put complete trust in a computer program. I took CPU-Z to be infallible. (It is a computer program, after all.) Yet I should have known better, that all machines contain errors.

The application must have misread something about my computer and spat out the wrong graphics port, which is unfortunate since it detected the rest of my hardware without fault. If I was thinking properly, I would have Googled the motherboard’s serial number and checked the specs myself. The first place I looked, the manufacturer’s website, had a page with all the pertinent information, including mention of the board’s “PCI Express Architecture.”

The new PCI-e card arrived in a few weeks. My father and I once again cracked open my desktop to install the new card. This time, it fit like a charm. Finally, I owned a real gaming rig. But guess what: The first game I wanted to play on my new rig wasn’t the hottest, graphics-busting megagame.

It was StarCraft.

Why? I don’t know…maybe I wanted to prove to myself that I’m not a graphics whore, that I wanted the new card for improved playability and not for pretty visuals. Also, I wanted to play through the damn thing without cheating. I remember years ago, on my family’s Windows ’98 system, I didn’t play StarCraft so much as “CheapCraft.” I would turn on cheats and blast my way through the campaign without an ounce of skill required. I was never good enough to play through the game fairly — that is, until I upgraded my PC. After that, the challenge seemed possible. I was man enough, and my PC was machine enough. Of course, pretty much any PC today is machine enough to take on StarCraft.

I didn’t expect the graphics to get any better with my beefed-up video card, but I had to stifle laughter when the blocky, pixelated Blizzard logo showed up on screen for the first time. Naturally, the low resolution of the intro carries over to gameplay. The graphics are not technically impressive by today’s standards, but they achieve the most important function of graphics in an RTS game, which is to differentiate the player’s army from the enemy’s forces. StarCraft makes identifying the three races easy based on color, shape, and animation, allowing the player to instantly discern friend from foe and assess the situation on the fly.

Although StarCraft is essentially 2D in perspective, it incorporates battle tactics that imitate a 3D environment. A “fog of war” darkens distant geography. High ground placement is important for seeing further into the fog and for increasing the range of artillery units. The fixed camera angle allows players to hide units or buildings from the enemy by concealing them underneath flying obstructions. Despite a low level of detail, the graphics serve well to support gameplay.

Versatile reflexes are essential to winning at StarCraft; the player who acts faster with the mouse-and-keyboard controls has better control over his or her units. Although the greater army usually washes over a smaller force, skilled players can use their outnumbered troops more effectively and whittle down the larger battalion. Good micromanagement — using each unit to its highest potential — can break through the enemy and overtake them. This shows that human control increases the overall usefulness, efficiency, and the underlying quality of artificial devices.

One might think that a computer, a machine that calculates variables at lightning speed, would be unbeatable at a game like StarCraft. Yet the inherent flaw I encountered earlier with the CPU-Z detection program arose in StarCraft as well. I was playing against the computer A.I. in a 1-on-1 game. Less than 5 minutes into the match, I scouted my opponent’s base and saw that its resource gathering was completely bonkers. It had over 15 units gathering from a geyser of Vespene Gas — a resource that three or four units can mine at once. The computer was scarcely mining from its mineral patch, the more common but more necessary resource in the game. It had up-ended its production and flipped it around, without a clue that it was completely wrong. The game ended quickly thereafter when I knew the A.I. had no way to rebuild its army. I encountered this glitch only on occasion in 1-on-1 matches, so it has no bearing on the campaign mode.

As you know, the main reason I wanted to play StarCraft was to beat it without cheats. I’m happy to say I did, and it wasn’t nearly as hard as I had expected. The thought of managing an army all on my own must have been really intimidating as a kid. What made it easy this time around was I discovered a way to play the missions that isn’t feasible when playing against a human.

In the story mode, it’s totally possible to “turtle and tech” — to build excessive defense while fully upgrading your army. Once you’ve equipped your army to the teeth, steamrolling the opposition is a simple task. Also, flying units are highly favorable in the single-player campaign. Units unable to attack the air present no threat and can be quickly killed. Otherwise, a mass of flying units easily swarms the opposing antiair. Through focus-firing (a micromanagement tactic), you can quickly pick off the enemy forces one-by-one without them putting a dent into yours. Suffice it to say, you can exploit StarCraft’s A.I. weaknesses in several ways. I have no problem with that, as I am now wise to the fallibility of machinery.

This is my story of my trial-and-error, learn-through experience first dive into PC upgrading — and the gaming that followed. The situation worked out for the better in the end, since PCI-e cards perform much better than AGP cards and at a fraction of the cost. Also, I feel like I learned a few things along the way. I realize I lack personal responsibility for pretty much all the technology I use on a daily basis. Sure, I can replace the parts in a computer now, but I’ll need good ol’ Bihn to diagnose and fix any problems that may arise later on.

I’m still one of those romantic PC users who enjoy their machine without fully comprehending what it does. In doing so, I take it for granted. Is this the right way? If personal responsibility is important in life, I should learn how to fix the PC or the car or the dishwasher myself. Then again, the lives of computer technicians, mechanics, and dishwasher repair-people are bound to the laziness of today’s common user. Their livelihood depends on our inability to understand technology, so to speak.

The final lesson I learned is that a human being is the part most vital to a machine. Human hands craft all technology. Humans control and refine the capabilities of machines, whether they are for cleaning dishes or controlling an army of Zerg. Most importantly, a human must test for errors, fix them, and then maintain quality at a high standard. For only human attention imbues technology with the full ability of its maker.

(Originally posted on 1UP.com)

For the comments:

- The title of my article parodies the title of a book. I also incorporate some ideas from the novel into my piece. Can you figure out which book I reference?

- Have you ever owned a “dishwasher of a desktop”? What made you invest in new parts, and how did you fare while upgrading?

- What are some other games that offer depth beyond their technical limitations?