This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Editor's note: I really dug Auditorium, but I had no idea its creators had produced follow-up Fractal until I came across Richard's insightful chat with Cipher Prime's Will Stallwood. Read the interview, then check out the demo at PlayFractal.com. -Brett

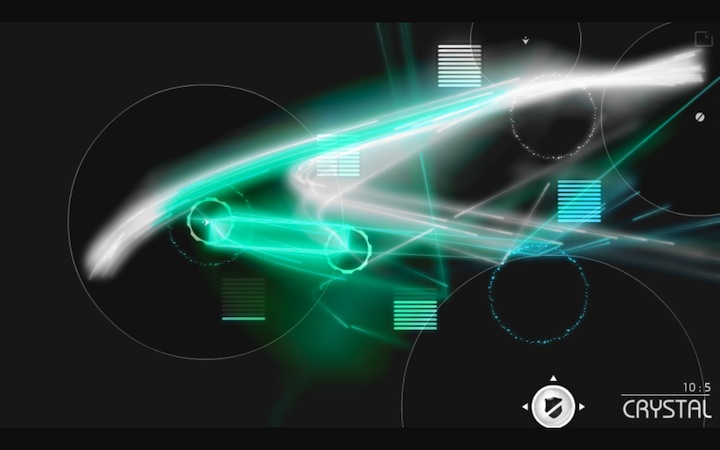

Indie developer Cipher Prime burst onto the scene in 2008 with their web-based music puzzler Auditorium, which won several awards and garnered viral success. Their integration of ambient music with beautiful graphics and animation won many fans. Auditorium has since been ported to the iPhone, and there is a console version in the works. Cipher Prime also released a follow-up, called Fractal, earlier this year, which keeps the same laid-back tone and immersive sound design but adds a more traditional puzzle game — one in the vein of Lumines or Bejeweled — on top.

I caught up with Cipher Prime cofounder Will Stallwood to ask him about the ideas and development behind Fractal, dealing with success, finding inspiration, and the nature of small-team game development.

Richard Moss: You have said previously that the idea for Auditorium came from playing around with a particle engine built for explosions. How did Fractal come about? Was it driven by a technology or a gameplay concept? Or perhaps something else?

Will Stallwood: Fractal started out as a really gritty board game based on Puzzle Fighter. [Cipher Prime co-founder] Dain [Saint] and I have spent way too much time playing that game, and we wanted to pay homage. The first prototype was played out on a piece of paper. Each player took turns “pushing” a fractal onto the board. You both played off the same board, and the objective was to simple create a set number of blooms before the other player. We then went and made our digital copy. Eventually, we decided it would be best to go basic and just create a single-player experience. Hopefully, we’ll get to revisit the multiplayer someday.

RM: I’d love to see it. For me, the way the game reacts to your successes and failures — changing in color and vibrance as though it was a living entity — is what elevates it above your typical puzzle game. It makes for a more consuming experience, and I love that I can gauge my progress simply through sensation, without looking at the HUD. What gave you the idea to have the world in Fractal wither or grow with the player? And was it hard to implement?

WS: Like all great ideas, Fractal was this really epic idea. The whole game was going to have this branching Fractal play-style. So, the original game spec we wrote had this whole wither and grow philosophy built right in. The trick for us was trying to find a way to do this with audio. We ended up having to build a whole audio engine from the ground up that could manipulate wave samples in order to simulate instruments. Then we built a little composer class that could take user input and convert it to the audio style we were going for. This whole system took a long time. However, now that we have it, our next games will benefit greatly. We have this really great audio demo called the Hex Synth I’ll have to send your way soon.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZzrJrmcItMU ]

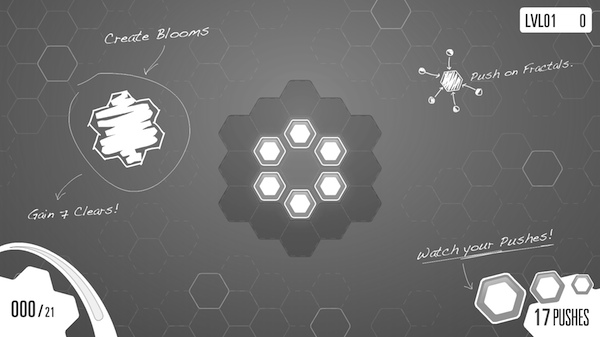

RM: I like the way you integrated tips into the background artwork. It’s something that seems to be gradually catching on with other developers, but I’m not sure I’ve seen it done so seamlessly, where it actually looks like part of the art rather than something layered on top. What made you do that instead of either a more invasive or more hidden alternative?

WS: I know I’ve seen that kind of design in other games, but I actually came up with the idea out of frustration. In our testing some people were able to pick Fractal right up and play, while others would be so confused they would run away instantly. I tried adding really obvious tips, but they just didn’t work. Eventually, I realized that they didn’t need to be obvious. If I made them a bit more subtle it could become a part of the game itself. For instance, if you type “makebloomsnotwar” while playing the campaign mode, interesting things will happen. Using the deco, we were able to add personality as well as fun tips and cheats along the way. I have to admit, it was also a bit nice to just sketch for a while.

RM: Speaking of “Make Blooms, Not War,” who came up with that tagline? It’s very catchy, and fits remarkably well with the theme and feel of the game.

WS: We love that tagline. Alisha Katzen was actually the one who came up with it. She was doodling in the office while testing one day and bam…awesome tagline.

RM: I’ve found that Puzzle Mode almost acts like a tutorial for the rest of the game, teaching the player how to rack up the big combos and chain reactions that are required to progress in the higher levels of the campaign or arcade modes. Was that intentional?

WS: From the second we put Puzzle Mode in, it became our teaching aid. With our beta testing, we were having lots of problems showing what was possible, and we needed a more controlled environment. We also kept making larger and larger blooms during our personal futzing around. It’s completely possible to create a 30X Bloom Cluster, which can be the entire stage on some levels. We wanted players to discover these kinds of cool tricks just like we did, but we needed a safe environment for any of those to really be possible. That said, it should never really feel like teaching. Learning all those funny tactics was fun to us, and we just wanted to share.

RM: I think it’s more my designer mindset that makes it feel like teaching to me — I’m always breaking down the mechanics and trying to figure out why things work a certain way. When I saw Puzzle Mode, I knew right away: “This is teaching me how the game works.” It wasn’t until I came back from playing Puzzle Mode to trying more of the campaign that I realized just how much it was teaching me, though. There’s still a lot of luck in my play, but I’m now getting a grip on how to do crazy things like clear the entire board with the “electrify” power-up or string together huge Afterbloom combos.

What’s your favorite mode in Fractal? Has there been much feedback on which game mode players prefer?

WS: Personally, I love all the Arcade Modes. Each Arcade Mode pushes me in different ways. Then there are levels 20-30. I just love those levels; they came together perfectly. Each one is like its own mini-challenge. I’m also a big fan of the Rubik’s Cube-style puzzles in Puzzle Mode that come up later in the sets.

Continue reading to find out Stallwood's influences, the Cipher Prime philosophy, Auditorium's future, and the difficulty of making a second game.

RM: The number of music-based puzzle games is increasing, especially on portable devices like the iPhone and iPad. Are you confident you can differentiate yourselves from the crowd?

WS: Geeezzz…I hope so. We really love making these kind of non-violent, music-based games, so I’d hate to see us stop. At the end of the day, as long as we have enough income to drift us by, we won’t stop trying. This may be the last puzzle game for a while though — we’ve been wanting to create more action-based titles. The Fractal dev cycle was very long, and we need to stretch our creative muscles in a lot more ways. We’ve also been working very hard behind the scenes on Auditorium HD, so we really are a bit puzzled out.

All in all, I want to see more music-based games. I don’t really see more games as a threat but a welcome challenge. We make games because we want to play them. If somebody else makes my next favorite music game, I’ll be the first one to let everyone know it’s amazing. In fact, we really try to let people know what games have influenced us when we’re making a title. I think it’s important to see what amazing games have shaped our ideas.

RM: I think it’s refreshing to see developers directly linking to their competition and letting everyone know up-front what influenced them. It’s something you see a lot in the indie scene, but not so much with the bigger studios. Do you see that as part of the indie spirit, or is it just that the big studios are kept on a tighter leash by their publishers?

WS: I’m really not sure what is going on there. As an artist, it’s really important to have influences. I feel compelled to share them and pay homage to those who have inspired me. In fact, I want them to get more recognition. I guess that could hurt the “bottom line,” but we’re only trying to run a lifestyle business. As long as we can make enough money to keep making games, that’s a win.

RM: Auditorium HD — is that the console version? Are you doing the port yourselves, or with help from publisher Zoo Games? And speaking of publishers, are there plans to work further with EA Mobile — perhaps with an iPhone or iPad version of Fractal, or an iPad-specific version of Auditorium?

WS: Auditorium HD is the console version. With the Zoo deal, we were lucky enough to have our choice of developers to work alongside with a co-development arrangement. Ultimately, we chose a two-man dev team like ourselves called Empty Clip. They have been doing a great job so far helping turn all our art direction into a reality while we push out new content.

As for the iPad, we’ve been throwing ideas around a lot amongst ourselves. We have the rights and can make it on our own, but it’s hard to justify. We don’t really know much about the marketplace, so it’s very much this dark void we’re unsure about.

Auditorium was a smash hit on the Web.

RM: Do you feel pressured by the success of Auditorium? It seems like a lot of people were expecting big things and were maybe a bit surprised with the direction taken for Fractal, which is more of a traditional game than its predecessor.

WS: Honestly, we felt overwhelming pressure. I think now that we’ve done a follow-up game, it just doesn’t matter anymore. There are so many independent game companies that only have one title. We wanted to make sure that wouldn’t be us. It’s hard having such a small team and always pressuring yourself to make new and interesting ideas. But I think we’re a bit relieved now. We’ve certainly changed our outlook a bit.

RM: Do you consider the small size of your company and development team to be a hindrance or an advantage? I mean, on the one hand, you’ve got way more flexibility and freedom to explore different ideas, but on the other, you’re hugely reliant on your fans and word-of-mouth, and you constantly run the risk of over-extending on a project that is just too big and ambitious for a small team to pull off.

WS: I think it’s both. But with our current contracts, we need a bigger team. One more of us could make a huge difference. Unfortunately, we just haven’t found anyone to fit that gap yet. For instance, this entire month and next month we will not be working on a single piece of new game design. We’ll be working on the final touches of Auditorium HD and getting all our Web sites and backend software in order. We want to be doing more game design, but these other things need to be done, and there just isn’t anyone else to do them. I think a lot of people get this impression our days are very lax and we just sit around playing or making games. In reality, game design is probably the smallest part of what we do. We are constantly trying to find new ways to free up more dev time.

RM: You are quite up front about your influences from within the game industry. Who or what are your key influences from the world outside — I’m thinking along the lines of artists, musicians, writers, objects, architecture, ideas, historical figures, and so on?

WS: Hmm…I’m going to really summarize this answer as there are just so many — this will be a rant. First off, I love the circus arts — everything from juggling, trapeze, down to straight comedy. In fact, I try my best to get over to the Philadelphia juggling club every week. I love teaching and think everyone should try to spread their knowledge. Right now my favorite musical artist is Amanda Blank ( I love her!) with Miike Snow following right up as a close second, then Tally Hall. I think the most amazing thing that ever happened to architecture was the Victorian flourish; it’s by far one of my most favorite designs of all time. I skate to work everyday. I have so many different types of transportation, from my motorcycle down to a unicycle. It’s really interesting how transportation can shape your life. As far as artists, there are just so many, so I’m not going to put one in front of another.

WS: Hmm…I’m going to really summarize this answer as there are just so many — this will be a rant. First off, I love the circus arts — everything from juggling, trapeze, down to straight comedy. In fact, I try my best to get over to the Philadelphia juggling club every week. I love teaching and think everyone should try to spread their knowledge. Right now my favorite musical artist is Amanda Blank ( I love her!) with Miike Snow following right up as a close second, then Tally Hall. I think the most amazing thing that ever happened to architecture was the Victorian flourish; it’s by far one of my most favorite designs of all time. I skate to work everyday. I have so many different types of transportation, from my motorcycle down to a unicycle. It’s really interesting how transportation can shape your life. As far as artists, there are just so many, so I’m not going to put one in front of another.

RM: According to the Cipher Prime website, your company philosophy is “to use the Internet to emote, to create a lasting and visceral connection with the user that lingers long after the browser window has been closed.” Is that still your philosophy, now that you’re more focused on game development? Do you think that you approach game creation differently to other developers, given your web background and stated philosophy?

WS: It’s funny you ask that. We’re working on a redesign of that site as we speak. Like any good agile company, our focus has shifted slightly. That philosophy still rings true, but the medium has changed. We do live by one quote here above others: “What would you attempt to do if you knew you could not fail?” It’s an anonymous coffee mug quote, but it has really shaped a lot of my life these days. In fact, the day we started this whole company mess we asked ourselves this question. Our answer was simple: “We want to make cool shit.” I do think we approach game design in a completely different way than other developers. But to what extent I am not really sure. Every dev I talk to seems just as lost as us, no matter how amazing their games are. Game development is a hard, scary road, and every game presents a new storm.