This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Editor's note: Allen's investigation into how female protagonists deal with romance in games like Mass Effect and Dragon Age is absolutely fascinating. Who knew video games were so forward-thinking in this regard? -Brett

When Atlus announced Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 Portable, I was excited to read about a new addition to the game: You could now play as a girl. Now, playing as a female isn't a novel concept — after all, Metroid's Samus Aran is 24 this year — but changing the gender of the protagonist in Persona 3 changes the entire dating-sim dynamic of the game.

Persona 3 mashes up the traditional Japanese dating sim with the traditional JRPG. One day you'll be fighting a giant monster shaped like Hulk Hogan, and the next day you'll be taking the student council president out on a date to the local burger joint. As you can imagine, the gender of the protagonist drastically alters how the dating-sim aspect of the game plays out.

Given my reading of Persona 4, I was curious to see how they would rewrite the game with a female protagonist in mind. For example, in the original Persona 3 you could play the male protagonist as a horn dog who chatted up all the girls. Could you do the same if you chose to play as the female protagonist? Certainly we know that a double standard exists in American society when it comes to promiscuity and gender, but how would Japanese writers deal with that situation?

While I was thinking of how to address this question, a line from Andrew Fitch’s 1UP review of Persona 3 Portable stuck in my mind: “Women are a huge portion of the dating-sim/life-sim target market, so it’s interesting that Atlus hasn’t really made a concerted effort to directly target them with the modern Persona releases until now.” Certainly the PS2 Persona games would be the perfect JRPG to directly target male and female audiences.

Then that I realized that the dating-sim/RPG genre that targeted both men and women had already been covered by another venerable RPG developer: BioWare!

We don’t think of Mass Effect or Dragon Age: Origins as dating sims, of course, because they exist in a vacuum in the American game market. Sure, Fable 2 pushes the life sim further by allowing you to have a family, but developer Lionhead certainly didn’t have winning moments in their game like this one:

At this point that I realized that not only is there a market for romances in games targeted directly at women, but that these romances have substantial followings. While the female characters from Dragon Age and Mass Effect have their fans, Alistair and Garrus are the only ones who could inspire thousand-page threads on the official BioWare forums. Certainly BioWare has hit a nerve with these romances — and there’s every indication that Persona 3 Portable will garner the same reaction if YouTube comments are anything to go by.

For a bit of perspective, chilyn, a blogger on the Dragon Age blog Grey Wardens, asked women why they love Alistair, and many explained their infatuation in the comments. Although examining why women identify with these specific characters could be a rich line of inquiry, I want to analyze the very nature of interactive romances themselves and show that virtual interactive relationships are easy to identify with because they provide a safe space for a positive representation of female desire. I’ll do this by looking at how game romances work and by comparing them to romances from noninteractive forms of fiction.

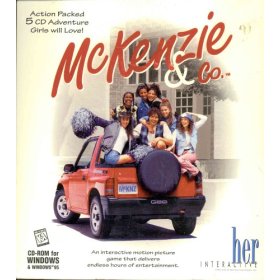

Dating sims have been a staple of Japanese video games for two decades now. But while men are certainly the bigger audience for dating sims or "gal games," developers have been quietly developing similar games for women known as “otome games” to moderate success. Early examples include Angelique, of which the third game in the series was featured on an episode of the TV show Game Center CX, and McKenzie & Co, one of the first games produced by Her Interactive. The dating sim is very much an equal opportunity genre and satiates both male and female wish-fulfillment fantasies.

And lest we forget, these types of games are so well known and pervasive in Japan that even Nintendo poked some fun at the genre in Super Paper Mario.

What’s noteworthy is that while these games may not have directly inspired BioWare (although Atlus most certainly borrowed from the genre when developing the contemporary Persona games), they feature the same type of dialog trees that BioWare uses to allow the user to interact with the other characters in their games. As a metaphor for conversation, developers naturally found it easier to give players a few responses to choose from, moving away from the more open and free-form text-based games of the early '80s.

One side effect of using dialog trees as a vector for interactivity is that conversations between the user and game characters are entirely reactive rather than proactive. The game needs to know how the player will respond to a character before it can proceed to the next line in the script. In Japanese dating-sim parlance, this is known as hitting a “flag,” or in layman's terms, a user telling the game that he or she is ready to proceed to the next event in the narrative.

For example, in both Dragon Age and Mass Effect 2, you must tell the game which character you wish to pursue a romantic relationship with. Garrus, Thane, and Jacob (or Jack, Miranda, and Tali) will never take the initiative to go after your character because the game designers do not want to force you to choose a lover. In fact, one perfectly valid choice is to not choose any of them at all.

Garrus’ romance being “flagged”:

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jrwCJxR1Xgk ]

Suddenly, because of the nature of how games produce interactive conversations, the player is cast in the role of sexual aggressor regardless of gender. Indeed, in a reversal of fantasy-based gender roles, Dragon Age’s Alistair is the virginal celibate warrior priest whom the player must seduce through various choices in his dialog tree. Even the sexually experienced Zevran will act bashful around the female player-character unless she “sets his flag” through a dialog choice and tells the game that she wants to choose him as her lover.

Given the demand for interactivity and player agency, games necessarily avoid the problems that many feminist critics have with romances in other media. Perhaps the most obvious example of a problematic depiction of romance is found in Twilight and the relationship between Bella and Edward. In her criticism of the Twilight novel series, Salon critic Laura Miller concludes:

Some things, it seems, are even harder to kill than vampires. The traditional feminine fantasy of being delivered from obscurity by a dazzling, powerful man, of needing to do no more to prove or find yourself than win his devotion, of being guarded from all life's vicissitudes by his boundless strength and wealth — all this turns out to be a difficult dream to leave behind.

The quote speaks for itself, but it’s fair to say that Miller finds the fact the Bella is very often the passive observer/victim of the narrative extremely problematic. The novel encourages passivity, as Bella is physically and socially rescued by Edward without any effort on her part.

Of course, this criticism is not limited to Western fiction — the same criticism could levelled at Japanese comics and cartoons for girls, known as shoujo manga or shoujo anime. Indeed, while texts such as Ouran High School Host Club and Kaichou wa Maid-sama feature extremely intelligent and capable heroines, they still pale in comparison to their absurdly rich and brilliant male love interests.

However, for the female protagonist in Mass Effect, Dragon Age, or Persona 3 Portable, this is simply not an issue. Because these are games, the player can’t be passive and wait for a strapping young hero to save them. Not only does the player have to seduce Alistair through dialog trees, but she also has to pick up her sword or staff and slay dragons alongside him. Since being passive and inactive is anathema to gameplay, games that feature a female protagonist have made the damsel in distress an anachronistic trope.

As such, Mass Effect’s Shepard is both a fighter:

and a lover:

It’s not that games have completely solved the problems of the representation of women. I’ll be the first to admit that games still unnecessarily sexualize, trivialize, and objectify women. But for a small segment of games inspired by or at least related to dating sims, both genders are presented as equals. The games don’t patronize female players (or men who choose to play as the female protagonist) by placing them in a position where they have to be passive and rescued by another character. The heroines are not only a part of the action, they are the first ones to charge into battle. With the romances themselves, players are given the opportunity to choose their partners and also take charge of their relationships.

Games empower romances featuring female leads by giving players agency that they are not afforded when they read Twilight or other similar novels. It is this sense of control that gives players ownership of their characters and also of their virtual relationships. Players don't just consider the characters “my” Shepard or “my” Grey Warden or “my” Persona User: They also see their love interests as “my” Garrus or “my” Alistair” or “my” Akihiko. It is this feeling of ownership and entitlement that makes these relationships so personal and positive, and these are feelings that I'm sure all game designers want their players to experience.