This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

For much of my existence on this earth, I have been an unashamed Civilization addict, Sid Meier's historically-themed strategy masterpiece. The series has done more to cultivate my interests today than anything else, helping to determine my majors in school (history and computer science), my fascination with interactive systems, and my goal of a career in game design.

So to celebrate today's release of Civilization 5, I wanted to take a moment to reminisce about my well-spent youth with the video-game series that defines so much of my past, present, and future.

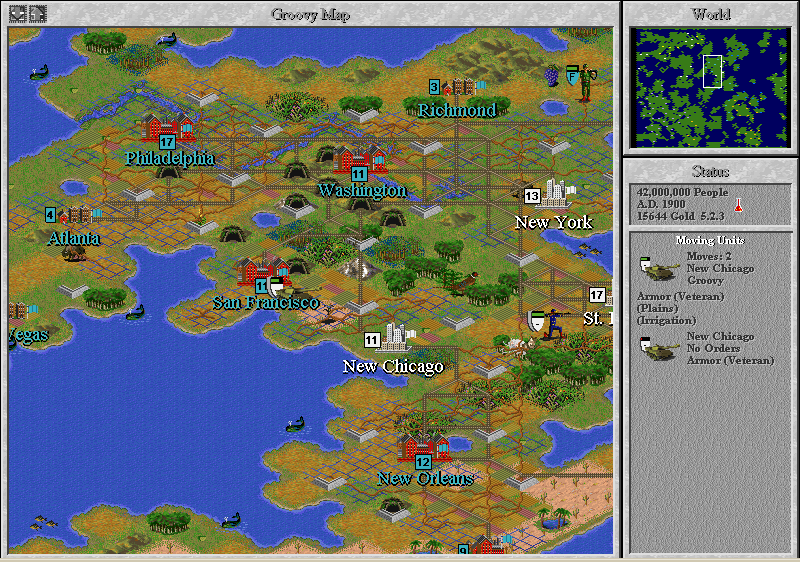

I was only four years old when the original Civilization came out in 1991, and I knew nothing of the game until a few years later, when my brother entered private school. He came home for break with Civilization installed on his laptop and showed it to me. I was hooked instantly — before I’d even played it. The developers had abstracted an entire alternate history of Western civilization into this simple game that offered so much emergent complexity.

The cartoon series Pinky and the Brain never seemed so relevant. I could rule the world as I thought it should be. Or I could get a taste of being a tyrant, sadistically heaping misery on friends and foes alike. All the while I learned about differences between social and cultural groups, that not all are created equal, and that everything has underlying rules and logic, except human emotion.

My brother had customized his copy of Civilization so that dialogue options in the diplomacy screens were different. The choices became rather less, ahem, diplomatic and included such provocative rebuttals as “GO FUCK A COW!” At the time, I thought this was some kind of social commentary, as if the developers were sticking it to the aggressive speech veiled by politeness of political discourse. You can imagine my surprise when a friend got the game and I saw the real dialogue options, which were much more in line with the usual halting politeness and veiled animosity of relations between rival historical powers.

I later obtained the Super Nintendo version and was astounded at how well the game had adapted to console play. This perhaps foreshadowed Civilization Revolution, with its more colorful graphics and a similarly streamlined interface that suffered only from the fact that it was trying to jam a keyboard with over 50 buttons onto a controller with only a half dozen. Not that I cared whether the series would one day get a console-specific version. I had what I wanted, which was Civilization in its full glory.

Next came Civilization 2, which is perhaps my favorite entry in the series. I played the game incessantly, always on the maximum possible map size, with rules customized so that Bloodlust (conquest victory only) was turned on and defeated civilizations stayed just that — dead. What makes the game so special to me, though, has less to do with the game itself and more to do with the circumstances in which I played it.

In the summer of 1998, my brother went on exchange to Germany and entrusted me with his laptop, which had Civilization 2 installed. My Ben Folds Five phase was at its peak (as was, incidentally, the band), and Whatever and Ever Amen became the soundtrack to my Summer of Civilization. I spent my days leaning back in an inflatable orange chair, with my feet on my bed and the stereo blasting, while I played Civ 2 and sang loudly out-of-tune: “She’s everything I want, she’s everything I’m not / Oh, I… / Have you got nothing to say.”

But like all good things in life, the summer eventually ended. My brother reclaimed his laptop, I went back to school, and I didn’t play the game again until I tracked down the Mac version a few years later, by which time the magic was gone.

Of course, by then I was just about ready to move onto the next Civilization, but I made a curious choice that would set my Civ addiction on hold. When my family bought an eMac in 2002, they allowed me to get one game. To this day I wonder why I opted for Age of Empires 2 over Civilization 3. AoE 2 was a good game; it just wasn’t Civilization good. Two years later I rectified my error in judgement and picked up Civilization 3 for the Mac.

I played the game evenings after school, then spent the next day thinking about my strategy. Would I suck it up and play nice with the Russians so that I don’t get drawn into a war on two fronts? Or would I simply say, “I’ve had enough of your crap,” and mobilize for war, with every city working the military production angle?

I never bothered going after the space race or diplomatic victories — too boring — and I still felt that the cultural elements of the game were lacking depth and subtlety. So I angled toward either conquest or domination victory, depending on my starting conditions: a big, well-resourced tract of land turned me to a domination strategy; anything else turned me to conquest.

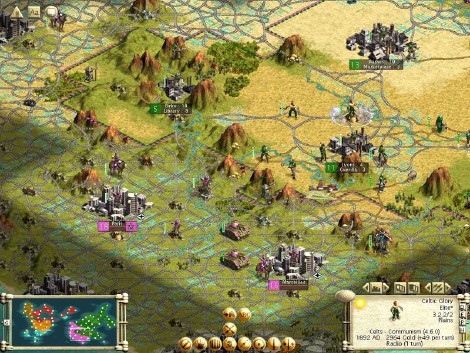

I arrived late to the Civilization 4 party thanks to a combination of an aging computer (we still had that eMac), the transition from high school to university, and the slow process of porting to the Mac. I finally caught up in early 2008, two-and-a-half years after the game's Windows release. Although I had my reservations (and still do) about the transition to 3D, Civ 4 blew me away. Civilization had always been a big, expansive, and deep experience. But Civ 4 was huge. One campaign could last upwards of 20 hours on the larger map settings, and the number of viable play styles dwarfed that of previous Civ games.

For the first time ever, I actually enjoyed taking the peaceful route, and with good strategy I was able to keep the other civilizations from blackmailing me or otherwise sparking armed conflict every few turns. I found enough depth in being a culture and trade power that the military side of things didn’t hold my attention any longer. It didn’t help that the conflict system was more or less broken, with most wars consisting of stacks of units (literally — you could pile dozens of units onto the same tile) sliding into each other, the one with the better combination of strength and numbers almost always emerging victorious. But the culture and trade systems possessed a depth unseen in the series so far, which intertwined beautifully with the religion, diplomacy, and micromanagement aspects of the game.

Civ 4 is also the first video game to make me think more deeply about the people, stories, and events that get lost in the abstraction. I wrote a short story earlier this year ("Untold Stories of War") as part of an attempt to come to terms with the growing disconnect between Civilization’s deep and at times realistic simulation of human development, and the real story of the growth and development of civilization, which is made up of millions of narrative branches, each affecting the very existence of hundreds of thousands of people who, in turn, each have their own stories and experiences that grow out of the broader cultural, religious, and societal trends.

If ever there was a game series that you could say has long-lasting educational benefits, surely it would be Civilization. The series has grown from a very simple-minded but open window into human history to become a deep and well-nuanced abstraction of the development of both Western and Eastern civilization. With each new instalment it becomes less mired in the Western-centric idea that technology is the sole driver of progress. It hasn’t got it right yet, but perhaps that’s for the best because history is always changing, much like the game and the people who play it.