This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

I have an interesting relationship with the game industry. Though one of the world’s largest game publishers employs me as a quality-assurance tester and I contribute to an independent game project in my spare time, I do pretend to be a member of the games enthusiast press on occasion. On a technical level, you could say that I’m caught in the middle of both the game-critic and game-developer camps, possessing some stake in both.

And while you could consider my involvement in each group relatively minor, it’s still difficult to be a part of one without ignoring or compromising the other. Whenever I feel the need to be critical of a game, the developer in me gets defensive. On occasions where I feel proud of the project I’m working on, my internal critic berates me for not being more evenhanded with my praise. Finding a balance between the two has been a challenge these last several months, and every time I think I’ve reached a middle ground, I worry I may have to give up one aspect of my gaming career to be more true to the other.

To be fair, it’s not like I’m knee deep in the artistic or coding aspects of game design, and I don’t head up a respectable enthusiast magazine or website. I’m a bug finder who practices journalism from time to time. But even from my minor level of involvement, I can see the conflicts that naturally arise when you muddle press and development.

But what's the conflict if both groups are ultimately working toward the same goal of producing great games? It has a lot to do with the way all of us (player, journalist, and creator) pit the industry press and the development community against each other. In reality, it’s no different than the relation between the press and other industries, but problems arise when you consider that the livelihood of each party rests on the other. At times, it makes for an incredibly tense battlefield.

The gatekeepers

Whether you’re a blogger or a full-fledged game journalist, you have a tacit responsibility to be true to the people you’re writing for. This holds true even if your modus operandi is to have someone pay you to play games. And this, unfortunately, is a reality despite the difficulty of breaking through the crust of the field. When you’re writing for other people — as you should be in this biz — you should be trying your damndest to give them what they need.

If it’s a game review, you want to let them know if this product is worth their time, using whatever metric. (I don’t solely mean game scores here.) If you’re reporting news, you should try to find the most informative, entertaining, and enlightening nuggets of info for your readers. Even cheat guides and lists carry the burden of relevance and duty.

The press should ideally work alongside game developers, acting as gatekeepers and disseminators of information in the way they best see fit. But the nature of the industry acts against this relationship. That is the problem. In a world where Metacritic's aggregate scores carry far more clout than they rightfully should, several negative reviews can strike a deathblow against an entire development team's livelihood. Granted, other factors are in play — a little, old thing called “sales numbers” comes to mind — but it’s hard to ignore the role of the pen (or the cursor) in determining the fate of a new title. Word of mouth travels fastest when the people with the biggest voices shout the loudest.

It’s understandable, then, that some developers have an antagonistic relationship with the press. Friendships between developers and journalists are common, but in the end, a writer has to serve the reader. And developers have to make their projects monetarily viable. It’s a difficult situation, exacerbated if either party burns a bridge in the process.

When you consider how much time and passion developers put into what they perceive as a winning product, hurt feelings often seem like the only likely outcome.

Sympathy for the devil

A colleague of mine once described members of the game press as “the enemy.” He said that their only purpose is to pick apart a studio’s hard work, ignoring the countless hours and sacrifices that go into making the simplest of games. I tried to explain to him the role of the journalist as gatekeeper, but since reviews had burned him so many times, he wasn’t in any condition to hear what I had to say.

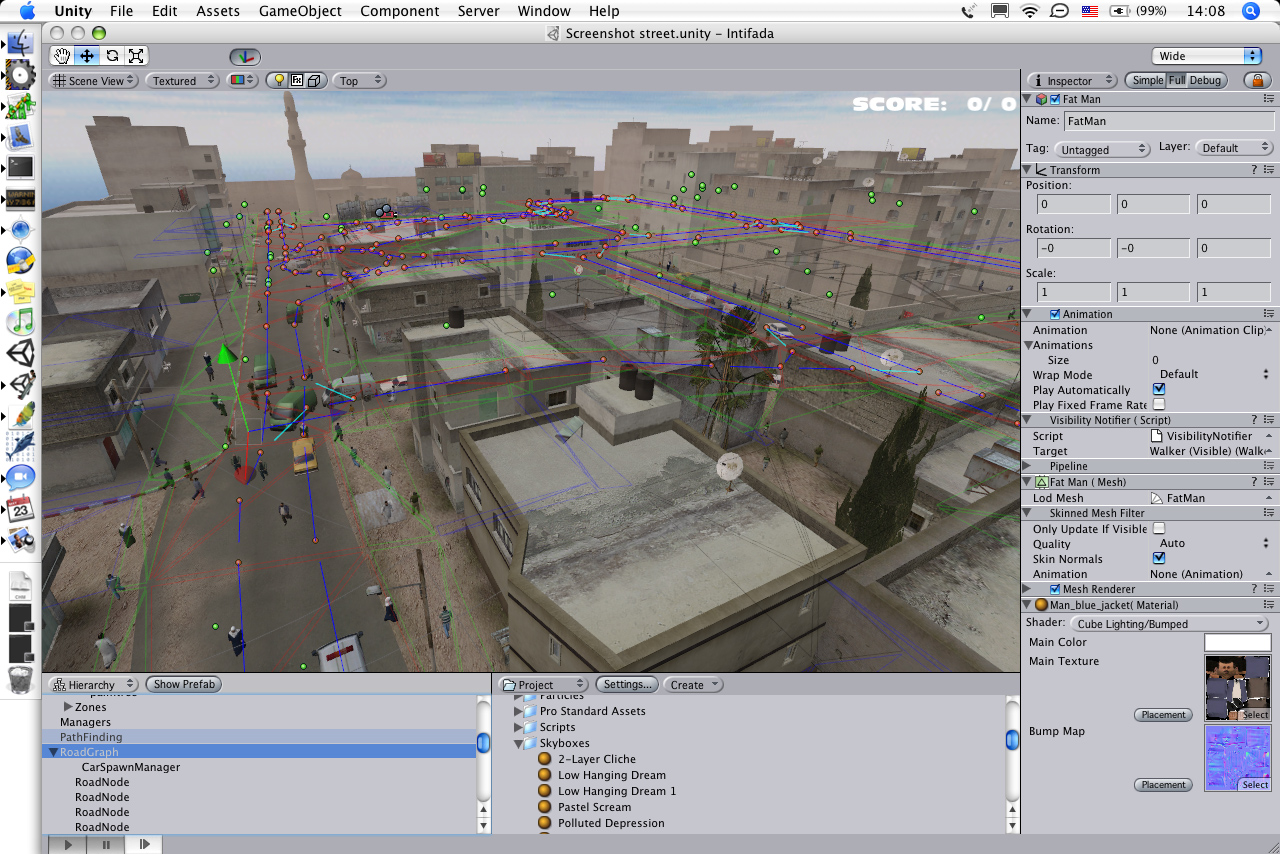

Game development isn’t easy. Even from my peon-level seat, I can see the work that goes into the process. It’s not a linear, cut-and-dry science. It’s frantic, and it’s matted with blood and tears. Game makers rush to succeed, not only in producing an incredible product but in creating something that will keep shareholders and producers happy as well. Game developers serve many masters, the hungriest of which is the consumer public.

Honest game developers have your best interests in mind. They want you to have fun, to enjoy this fruit of their labor, and to hopefully appreciate the effort. That's the ideal relationship, but in this marketplace of bountiful choice, it’s easy to see the flaws in every apple in the bunch, and the most vocal of consumers are quite picky with their produce. In turn, so must the gatekeepers.

When a game developer strikes out vocally against negative press, the common internal complaint is that nobody on the critical end is taking into account the effort that went into making a game. They feel that journalists ignore the pain and sacrifice that goes into development, without sympathy. Or maybe, they just didn't "get it." Development teams sometimes disregard the opinions of the press because of this perception. After all, if you can’t make a game, what gives you the right to critique someone else’s hard work?

I can understand why game critics claim that game developers often get too attached to their projects due to personal involvement, developing a myopic perspective that keeps them from being critical about their own work. It's a bit of a cop out, but when you go out of your way to be as honest and fair as possible, only to get it thrown in your face because what you wrote wasn't "nice" enough, it's not too far off base. It’s a valid — somewhat blanket — complaint about the way some studios react to negative press, though such reactions only further exacerbate the situation.

Stuck in the middle

The unnecessary battle lines are pretty blurry, even when you’re on one side or the other. But what if stand astride the line? This is the situation I find myself in on an almost daily basis.

When I plan a potential article, I always have to consider my employer. Will I be using an inside connection to get information or an interview? Will my opinion reflect on my employer? Will it create a conflict of interest, or destroy my ethical appeal?

Likewise, when I have to give honest opinions and feedback on the titles I work on, I worry about my minor press involvement. Am I being too hard on the game by looking at it critically from every point in the project? Will my other affiliations make me an enemy of my development team and taint my feedback? Will they treat me differently? Are they fearful I might break non-disclosure agreement and report on my work, despite my diligent attempts to be vague about what I do and where I do it?

Thankfully, everyone I’ve dealt with thus far has responded positively to my full-disclosure policy regarding my work, both professional and otherwise. While I've had a few issues in the work place, most of my conflicts have been on a personal and ethical level, not professional. They arise from such a personal, deep-seated love for games that I've probably involved myself in more facets of their creation than I probably should have.

Regardless of the difficulties, I’ve decided to keep doing what I’m doing. I’m going to keep working to further my game development career while I simultaneously dig deeper into the enthusiast press in my own way. It’s been an interesting ride so far, and until an outside influence forces me to give up a particular aspect of my involvement, I’m going to stay the course. People in my situation have more than enough rope to hang themselves with ten times over, but maybe we can use it to tie some better bonds. We’re all on the same side, anyway. One day, we’ll find a way for everybody to win.