This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

When Heavy Rain's David Cage recently likened game cut-scenes to the story segments of porn films, I couldn't help but laugh a little; a lot of games do feel like that. When I was playing Metal Gear Solid 4, its exposition felt very empty and pointless. Unlike previous entries in the series, Guns of the Patriots' story bored me to death with meaningless dialogue and intellectually vacant narrative. A shame, considering how the previous games successfully blended high-quality cinematography with stealth gameplay, giving players the feeling that they were immersed in a spy flick.

Metal Gear Solid 4, in short, sums up everything that's wrong with a lot of video-game narratives these days. It demonstrates the gulf between story and gameplay, and how cut-scenes often only provide some sort of vague grounding to the action.

On the flip side, some titles emphasize story first and gameplay second, though these mostly take on the form of adventure games like Broken Sword, Monkey Island, and Grim Fandango. Here, the puzzles function as barriers to continuing the narrative, which is what many adventure gamers are there for.

More and more developers, however, try to blur the boundaries and forge a symbiotic relationship between gameplay and narrative. These kinds of games spam a variety of genres — RPGs, shooters, action adventures, even puzzlers — but share a common quality: their stories couldn't translate to another, non-interactive medium without losing significant impact. After the jump, I outline five of my favorite examples and what makes them work so well.

[Warning! Potential spoilers ahead for: Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 4, Portal, Deus Ex, BioShock, and Mass Effect 2. You've been warned.]

Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 4

[Note: I haven't played Persona 3 yet, which many people tell me has similar ideas.]

Taking place over the duration of a Japanese school year, Persona 4 tied characterization with gameplay via its Social Links system. Spending time with your peers increased your Social Links, which, in turn, let you create different Personas. And these character developments also affected the narrative: The player learned more about characters that he had made the strongest Social Links with.

The narrative, in turn, also dictated the dungeons you explored, and the abducted character's worst fears directly influenced the layout and theme of the dungeon.

Very few Japanese RPGs offer such an accomplished mix of narrative and gameplay. Most rely on the story to complement a traditional RPG system, or cynically slap JRPG mechanics on top of an anime tale, but developer Atlus made the effort to really merge the two. When players care about the mechanics as much as they do about character development, that's a really rewarding experience, and one I feel only games can deliver.

Persona 4 would be utterly outstanding if it weren't for the underwhelming voice acting and some script issues. No wonder many consider it one of the finest JRPGs in recent memory.

Portal

Portal was a tough choice for me to mention in this piece, but the more I thought about it the more I felt it rightfully deserved a place. While it would've been a great puzzle game even without any narrative at all, the game's scenario and humor rank it up there as one of the more forward-thinking narratives of the last decade.

However, developer Valve didn't just write up a few gags and then call it a day. They successfully managed to tie player emotions to an inanimate object: the Weighted Companion Cube. Gamers had to carry the Cube from room to room only to be told later on to incinerate it, which in turn spawned a slew of fan-made Weighted Companion Cube tributes and, later on, Valve's very own plush toy.

And the Weighted Companion Cube was there for a very important reason, fan obsession notwithstanding. With its demise, it taught the player a new gameplay mechanic that was instrumental in the final boss battle with GLaDOS.

The final battle also neatly joined narrative with gameplay as GLaDOS first pleaded with you not to destroy her and then insulted you in a more juvenile fashion as you incinerated physical parts of her. The impact of GLaDOS's reaction and the satisfaction (not to mention the slight guilt) of tearing a now-near-defenseless being into pieces was an accomplished piece of gameplay and storytelling.

Deus Ex

Linearity is almost a bad word these days, and games like Deus Ex are to blame. Choices, branching dialogue, and deep character customization really struck a chord with gamers. The fusion of narrative and gameplay pervaded the whole experience. The "right" dialogue choice led to better rewards, and the attitude the player took — whether it be stealthy, gung-ho, or otherwise — had a direct impact on how other characters viewed you.

Through the early stages of the game you had the choice to subvert authority or conform. Conformity reaped greater rewards but had you doing sometimes morally repugnant things, such as assassinating an unarmed man in cold blood. Subversion may not have offered as much extra cash, augmentations, and gear, but it did allow you to express yourself in a way that many games don't. If you wished to show a complete and utter disregard for hostages, for example, then letting them die in a subway station explosion was perfectly acceptable within the framework of the game's story.

This freedom of expression applied to character building and direct narrative choices alike. For example, buff a character out with more physical-based attributes and you could force open a door instead of hacking or picking the lock. This kind of malleable gameplay worked within the narrative by allowing characters to adapt to your actions and taking a hostile or more conciliatory attitude depending on what you just did.

Juxtaposing all this gameplay freedom with a dystopian conspiracy theory plot really drove players to want to earn their freedom, in narrative terms, in a way that removing our gameplay choices would hinder.

BioShock

BioShock's narrative was less about a plot and more about an idea. The idea of a city constantly under physical pressure from the huge weight of the sea above contrasted with Andrew Ryan's social philosophy — of freeing the elites from the shackles of the state and non-elites in general — was immediately striking, from the morally repulsive human experiments that inevitably followed to the collapse of law and order.

Rapture's story was not told directly, but through recorded logs and the mess that the entire city was in. Each nutcase you encountered throughout the game had been pushed to their limits, and the real story was what had happened to them before, not now. Finding these logs, which could be well-hidden, was a gameplay matter. The reward was learning a little bit more of the narrative.

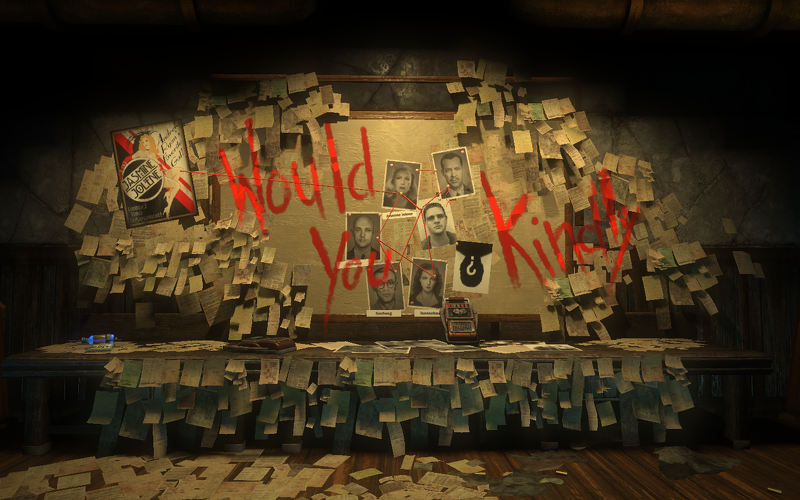

But BioShock didn't just fuse story droplets with gameplay; that would be disappointing. The real standout part of BioShock's narrative was the 'would you kindly?' moment. It was an ingenious plot device that brought all of Rapture, many of its citizens' stories, and the game's analysis of objectivist philosophy to a head, while challenging the staple industry practice of barking orders at the player via the radio. Irrational Games went the extra mile by turning such an established core gameplay mechanic into a major part of the narrative.

'Would you kindly?' has gone down as one of the finest twists in gaming history, and also marks an observable turning point in BioShock's merging of narrative and gameplay. After the game has blown its load, run out of ideas, and has nothing left to tell, the gameplay and narrative divide becomes more distinct — the story feels plotted (there in spite of the gameplay), and the whole package begins to crack at the seams.

Mass Effect 2

While Mass Effect 2's plot felt a little static as far as the trilogy goes, what story it did have — a very strong, character-driven piece — tied well into the gameplay.

Menial tasks such as mining various materials from planets led to ship and weapon upgrades, which were vital to you and your crew surviving the final mission (and make no mistake, self-sacrifice is a narrative option in Mass Effect 2), while use of the developed Paragon or Renegade traits could earn you valuable conveniences such as avoiding fights, getting an upper hand on an enemy, or store discounts.

But more importantly, developer BioWare took the character relationships one step further by adding a loyalty system. Your actions during the special loyalty missions and the crew conflicts afterwards had a lasting impact that stretched right through to the game's 'Suicide Mission', where the life and death of your team hung in the balance.

A charismatic Shepard with either strong Paragon or Renegade tendencies will dissolve disputes between the crew either through fear or compromise, while a Shepard without either of these skills may wind up losing someone's loyalty, which could mean their sacrifice at the end of the adventure.

With Mass Effect 2, BioWare took the concept of the expendable soldier we've seen in countless games, put a face and a personality to each one, and made a gameplay mechanic out of ensuring they didn't die for fear of suffering a less-than-satisfactory ending rather than the dreaded Game Over screen.

By making these outcomes permanent as far as your save file goes, Bioware made NPC death less of an irritation and more of an objective you can fail — complete with emotional repercussions.

Of course, many more games achieve a great blend of narrative and gameplay than what I mentioned above. If anyone thinks I've committed a cardinal sin by not including 'game x', then feel free to blast me for it in the comments.

Chris Winters is an unemployed (and unpublished) novelist and wannabe games writer. You can check out his stream of reviews from his backlog on Been There, Played That, or get in touch with him on Twitter: @akwinters.