This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

All of the good stories in any medium have a conflict of some sort. One of my favorite books, John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, revolves around the novel’s eccentric antihero, Ignatius J. Reilly, his conflicts with modern society, and his lack of employment to create one of the best stories I’ve ever read.

Likewise, Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, one of my all-time favorite movies, deals with the conflict between generations, growing up, and the problems with modern Japanese society. As is typical with many of his films, Miyazaki, a director known for pacifist themes, doesn't resolve the conflicts he presents through violence.

Though some of the best books, flims, and TV series revolve around acts of violence, many of the finest works recently produced do not. All the different permutations of story, conflict, and resolution allow everyone to have something they like, and our storytelling culture is richer for it.

Video games have lost this message somewhere along the line.

As in previous years, developers have crafted many of 2010’s hottest narrative-driven titles around killing. Whether you're shooting enemy soldiers in Call of Duty: Black Ops or jumping on a Goomba’s head in Super Mario Galaxy 2, most of this year’s games revolve around violent acts and death, seriously limiting the breadth and scope of the narrative in the process.

Needless to say, most of 2010’s nonviolent games, like Chime and Dance Central (to name just a few), don’t need a narrative. Instead, they opt for unique gameplay and pure fun to drive appeal. The attitude of gamers toward nonviolent games tends to revolve around quirky and abstract mechanics rather than having a fun and entertaining story.

With all of that said, I'm glad to note that some of 2010’s top games have embraced pacifism. In some cases, nonviolent gameplay has marginal impact on a game’s narrative. Other times, it completely shapes the type of story the creator is telling. Whatever the level of implementation, these games either allowed or forced players to resolve conflict through nonviolent means.

Following in the pacifistic footsteps of all the series' entries since Sons of Liberty, Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker gives players the option to disarm enemies via hold-ups, instead of shooting them. In usual Hideo Kojima style, using these stealthy, nonlethal means as opposed to all-out violence gains the player rewards. For instance, players can capture enemies who aren’t dead, allowing them to utilize their skills in the Outer Heaven Motherbase. Also, the manner in which you captured the enemy determines how long they’re out of action. Those who were captured with the least amount of ruction will join your team straight away, while an injured soldier may spend some time in the medical ward before you can use their skills.

Similarly, utilizing stealth and not attacking your enemies in any way leads to the highest mission rankings. This adds lots of replay value to the game, in addition to a peaceful message which explains to players that, at least in Metal Gear games, violence isn’t the only answer. It’s just a shame that your pacifistic actions have no discernible impact on Peace Walker’s plot. Whether you try your hardest to avoid killing or go all guns blazing, the story told is exactly the same.

In contrast, some developers believe that pacifistic gameplay provides options that may enhance nonlinearity. Players have a choice of when and when not to avoid conflict. Such games tend to employ “evil” and “good” statistics which fluctuate depending on your actions. They allow you to avoid conflict either through threats or through peaceful diplomacy. 2010 games like Mass Effect 2 and Fallout: New Vegas extensively employ such gameplay, and your actions can have a lasting effect on the plot.

In the case of Mass Effect 2, many of these actions carry on from the first game, allowing you to reap the rewards of your previous actions. The more peaceful “Paragon” speech options allow Shepard to talk potential adversaries out of fighting. This highlights the benefits of avoiding a fight or offering an alternative solution besides violence. However, these moments are few and far between, and extensive life-or-death fighting segments often link them together.

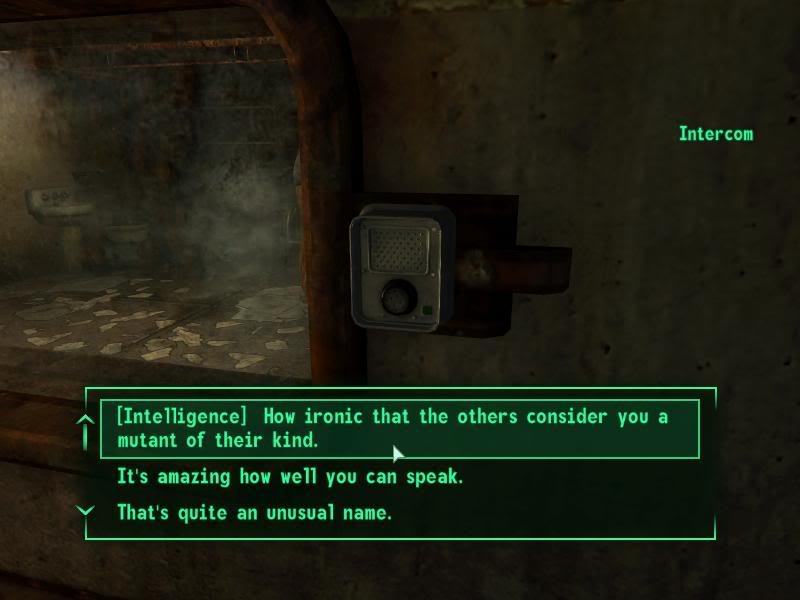

Similarly, Fallout: New Vegas allows you to use speech to resolve possibly violent conflicts. Having an advanced knowledge of one of the game’s many skills opens certain dialogue options. This means you can acquire items without killing or diffuse a conflict between two characters without picking a side. Such nonviolent options reward the player with more experience points, a companion to accompany you on your travels, or a happy ending to a questline.

On the other hand, with the myriad of skills available, no single player can become the master of them all, and although players can make a pacifist run of the game, the designers never intended for anyone to do it. It’s an extremely difficult community challenge that reaps no in-game or narrative rewards.

Unfortunately, in games like Mass Effect 2 and Fallout: New Vegas, the average player will get their hands dirty. Peaceful means become an occasional curiosity rather than a lifestyle choice, and under close examination they quickly fall into the most typical gaming trope: violence.

Some of 2010’s games, however, force the player to employ skills besides their trigger finger to resolve conflicts.

Ace Attorney Investigations: Miles Edgeworth, like most games in the genre, doesn’t have any violent gameplay segments. But unlike other adventure games, which sometimes resort to violent ends (like the use of voodoo dolls in this year’s remake of Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge), Ace Attorney Investigations centers around the pursuit of truth and justice.

Instead of dispensing the player’s idea of direct justice — violence, killing and, revenge — Ace Attorney Investigations sees players delivering the violent killers into the hands of the law. The gameplay charges players with gathering evidence, while combat involves debate, logic, and rationality, as opposed to pointing a gun and pulling the trigger.

Likewise, Last Window: The Secret of Cape West is a tale of endings, departures, and hidden secrets. It tells many characters’ stories, each with their own conflicts and dilemmas, and the player solves them all without firing gun, slashing a sword, or fighting in any manner whatsoever. Instead, players use their investigative powers and puzzle solving abilities to uncover the past of an old hotel and shine a light on the truth hidden by those out to cover up their immoral and violent acts.

The fact that both Ace Attorney Investigations and Last Window revolve around murders means that their gameplay doesn't have to. The plots of both games rely on intrigue and different types of conflict: problems the player can't solve simply by firing a gun.

If games in 2010 have shown us anything, it’s that pacifist games can find an audience within the industry. When the majority of players take the “good guy” route, it shows that pacifism is a viable and, more importantly, fun gameplay option which helps broaden the types of stories video games can tell.

Chris has spent 2010 graduating from University, writing a novel, and playing lots of pacifistic games. This is his entry for December's Writing Challenge, and you'll be glad to know his last article of the year. Expect normal service to resume next week. You can find him on Been There, Played That!, or via Twitter.