This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Interplay: From Bards to Bombshells

1983 – Present

Interplay once dominated computer role-playing games in the late eighties alongside its peers. Although they would later be known as a publishing powerhouse responsible for Black Isle's Fallout series and Planescape: Torment in the late nineties (along with the revolutionary Descent franchise), it started with an idea, a game, and a programmer who wanted to kill lots of monsters.

Interplay once dominated computer role-playing games in the late eighties alongside its peers. Although they would later be known as a publishing powerhouse responsible for Black Isle's Fallout series and Planescape: Torment in the late nineties (along with the revolutionary Descent franchise), it started with an idea, a game, and a programmer who wanted to kill lots of monsters.

Brian Fargo wasn't the stereotypical coder living in his parent's garage or a student at a place like Caltech. He was a sprinter on a track scholarship when he walked out of school to work on his first game: Demon's Forge. Like Richard Garriott and Jon Van Caneghem (New World Computing), his house was literally his office as he managed marketing and sales from his bedroom.

The company he put together around the game was sold in '82, which pocketed for the then-19-year-old Fargo a cool $5,000. Interplay wasn't around yet, but a company called the Boone Corporation had folded some time afterwards and left quite a few gifted programmers without jobs. Several of its laid-off employees — including Rebecca Heineman — then banded together with Fargo to help found Interplay with a little boost from a generous $60,000 windfall from a new client.

But not to make games.

Interplay's first contract was from World Book Encyclopedia to do a series of small titles. That didn't stop a young Activision Inc. from stepping in later and handing Interplay a contract for three adventure games to the tune of $100,000. Despite creating Mind Shadow under contract, Interplay was still an indie, and that left the door open for Electronic Arts to publish one of the genres most memorable CRPGs.

The Bard's Tale was the result: a simple-to-use party system, a wide variety of dungeons, animated monster portraits, and a magic interface that relied on knowing the four letter codes for each one as a form of copy-protection. It also helped that The Bard's Tale was far more forgiving when it came to death when compared to Wizardry's then-brutal incarnations.

Although the series wasn't known for having interactive NPCs and consisted of combat-heavy dungeon crawlers, each game relied more on a player's imagination to fill in the blanks when it came to story; however, The Bard's Tale series would begin weaving its own mythology in between its chapters. Vast dungeons filled with devious traps, darkness shrouded halls, spinning floors, and mobs of monsters proved enough reasons to religiously back-up character disks.

As fantastic as the games were, The Bard's Tale series also had its own ups and downs. As Rebecca Heineman recalls in an interview with Matt Barton on Gamasutra, the second game was intentionally aimed at killing players (via the Death Snare dungeon puzzles) than in being as fair as the first and third games. This was apparently thanks to the Lead Designer Michael Cranford's preference for being the kind of me-against-everyone Dungeon Master who likes seeing players die. But as Fargo's high-school friend, I guess he had earned a little leeway in what he wanted to do.

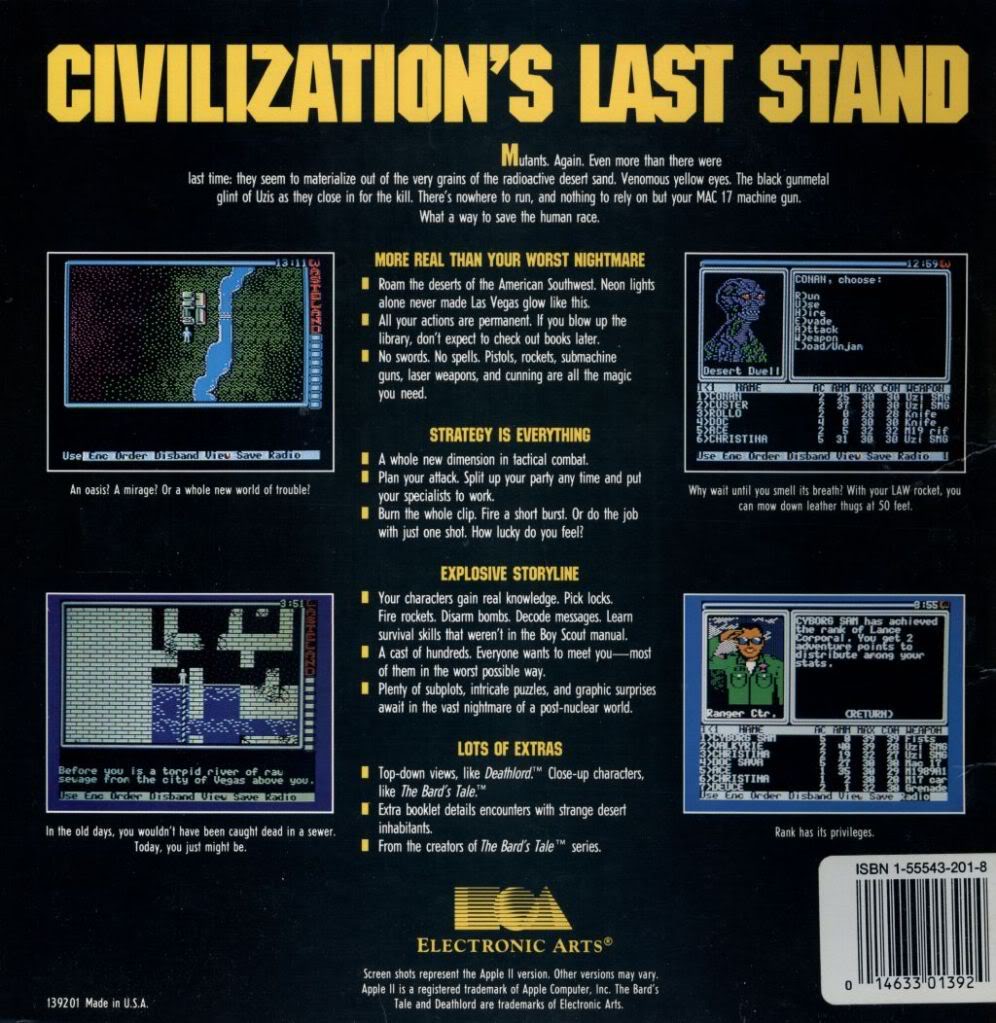

In '88, Interplay would go on to kick elves, dwarves, and orcs to the radioactive curb in Wasteland, a post-apocalyptic CRPG that shied away from swords and sorcery and replaced them with automatic weapons and a vast, player-customized skillset. Its minimalist looks and top-down tiled approach went against The Bard's Tale's first-person perspective, but the wide array of skills and open-ended depth of its gameplay more than made up for what it lacked on the surface, which provided ideas that would later be passed down to titles such as Fallout.

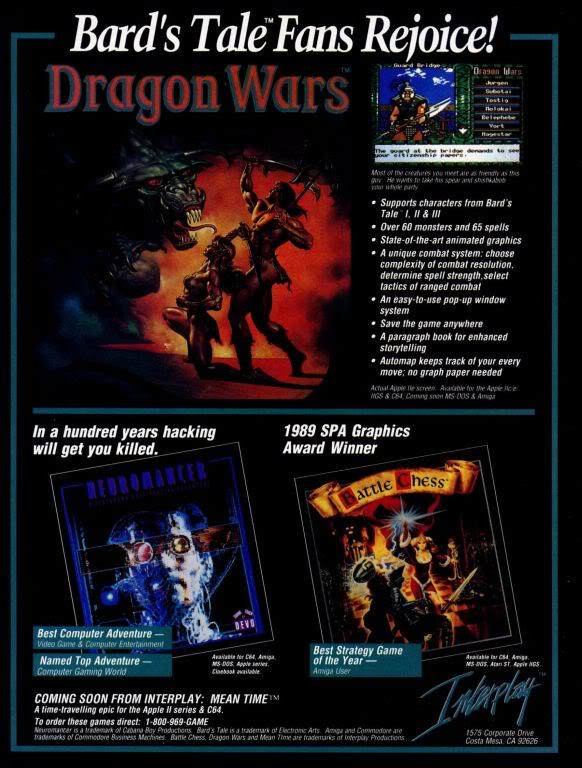

Dragon Wars, considered by some as the spiritual successor to The Bard's Tale, went back to high fantasy in '89 — complete with fancy graphics and a hybrid of features that felt as if they were a culmination of Interplay’s work from Wasteland and The Bard's Tale. It also exemplified the kind of storytelling that Interplay had been known for. Remember, this came out when the Cold War was still on, so casting dragons as the equivalent of nuclear weapons in a world gripped by magical oppression were intentional real-world parallels.

And as cool as that might sound, that wasn't what Dragon Wars was supposed to be. Instead, it was supposed to be The Bard's Tale 4.

At the time, Interplay looked to break away from EA's publishing empire and would eventually become an affiliate with Mediagenic (which was actually Activision suffering from a bout of identity indecision). Unfortunately for them, EA owned The Bard's Tale trademarks — not only the name, but the world and everything associated with it . Predictably, EA didn't take too kindly to Interplay’s move and literally took its Bard's Tale ball and went home, which forced Heineman and the rest of the developers to leverage in the changes at the last minute. At least now I know why the dragons didn't look like…well…dragons. But as last minute fixes go, kudos to Heineman and company for actually making it work as well as it did.

Interplay had also adapted William Gibson's Neuromancer as a hybrid adventure/RPG, which brought the cyberpunk classic to PCs. Varnished with every cyber'ed syllable from Gibson's universe, walking the world and then jacking into cyberspace to duel ICE and nigh-omnipotent A.I. watchdogs protecting their master's secrets was as close to the vision of the book as anything else would approach at the time. Software and cyberdecks replaced swords and armor, and character interactions were handled as an adventure game in 'the real world.” It was an amazing title with a soundtrack by Devo, and it ran pretty well on a computer with only 128K of memory.

Interplay was also renowned for several other unique titles under its belt such as Battle Chess and Borrowed Time as well as bringing in actual writers to help with game design such as Arnie Katz, Bill Kunkel, and Michael Stackpole.

But Interplay wouldn't survive as a RPG powerhouse.

Read on to page two for Interplay's fall from grace.

Although the once-revolutionary Stonekeep had been released in '95 on PCs to some fanfare and critical acclaim complete with a hardcover novelette, its grid-based gameplay still felt outdated when compared to the free-roaming worlds of the Ultima Underworld series and Bethesda's The Elder Scrolls: Arena. Game stopping bugs on release required players to dial into Interplay's BBS (Bulletin Board System) if they wanted to finish the game. After four years of development and several million dollars, it wasn't quite the blockbuster that everyone expected it to be.

Consoles were also busy making their own marks with Japanese RPGs such as Earthbound andChrono Trigger on the SNES in '95, and those proved to be more popular than CRPG ports.

Strong titles such as Descent and their Star Trek-based adventure games had also shifted Interplay’s focus away from CRPGs, especially in the wake of flubs such as Descent to Undermountain, which attempted to adapt Descent's engine into a CRPG setting with grim results. I remember killing a lich — something like an undead über sorcerer that no eighth- or ninth-level character should ever solo — simply because it was stuck behind an object and couldn't get to me.

Even though Interplay had critical successes with several of its titles, the company continued to bleed money. Since '95, Interplay reported a stream of losses. And then in '98, Fargo decided to take the company public to drum up funding. It would also be (as some might put it) the beginning of the end. Despite a strong showing in the early months of its (reduced) IPO following June, the company's stock went into a tailspin in October after reporting massive losses of about $15.5 million dollars — nearly half of its already depressed value.

And then in '99 in walked Titus Interactive with deep pockets, buying enough of Interplay's stock to appoint Titus founders Herve and Eric Caen as leading board members. But who were these guys? Answers vary on who you ask. Some simply regard them as investors, while others look at them as the sole reasons for why Interplay imploded.

Titus Interactive was a powerhouse when they focused on PC games in Europe, but among the console crowd I remember them for their largely awful library. Both my friends and I would simply have to see a Titus symbol on a game to know that it would probably be horrible — kind of like a lot of the older Acclaim titles. Still, someone must have liked them. They had enough cash to gain a small (and then a controlling) interest in Interplay a few years later in 2001 — literally seizing the company. Yet, even it couldn't stanch the flow of money from Interplay as losses and debt continued to mount.

Moving into the console space ultimately proved to be a late and unsuccessful move for Interplay, something that several of its rivals, such as Bethesda Softworks and Bioware, had already tasted success with. Even with critically acclaimed hits such as Volition's fantastic Freespace 2 in '98 on PCs along with the Descent series, its PC audience — their main source of income in better days — continued to dwindle.

Interplay's meager attempt to refocus on consoles also gutted its PC presence even further. Among the casualties were those at Black Isle whose work included Bioware's Baldur's Gate series, Planescape, Icewind Dale, and a canceled prototype of Fallout 3 (codenamed Van Buren). But its developers would land on their feet elsewhere at such places as Troika and Obsidian Entertainment.

In 2002, Brian Fargo would leave the company he had founded. Speculation at the time cited differences between himself and the new bosses at Titus — Herve Caen in particular — which turned out to be true to some extent. But it was clear that Interplay's golden days were far behind it as it struggled to find its place in the changing market.

Fargo would eventually go on to found a new company, inXile Entertainment, where in 2004, they released The Bard's Tale as an action RPG. As humorous as it was and despite the name, it had little to do with the original series. Part of the reason is that EA is still holding on to its Bard's Tale ball (though they apparently allowed inXile to use the name). Surprisingly, EA did sell the Wasteland rights to Fargo in 2003, though, nothing has come of it other than the potential for another post-apocalyptic playground (and, hopefully, not another ARPG like Brotherhood of Steel).

Unlike a few of those on this list that simply disappeared into history, Interplay's "end" was riddled with a series of financial mishaps. In 2002, Interplay's stock was delisted from NASDAQ. In the years since Fargo's departure, Interplay had been subjected to a number of embarrassing incidents, which included failing to pay its employees for several weeks and eventually being evicted from its own property in 2004. Parent company Titus Interactive would then declare bankruptcy (and was later liquidated) in 2005. But it wasn't the end. Interplay miraculously clung on to life like a rotting, undead corpse that refused to die when it returned to the web with a new look in the same year.

In 2007, Bethesda bought everything Fallout related from Interplay, though, Interplay claims to have licensed the right to make a Fallout MMO that has led to some contention between both parties in the courts. But the company that had ruled the late eighties into the late nineties as a shining CRPG paladin had long left the dungeon.

Check back next week for FTL Games: Less Was More.