This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

New World Computing: Explorers Welcome

1983 – 2003

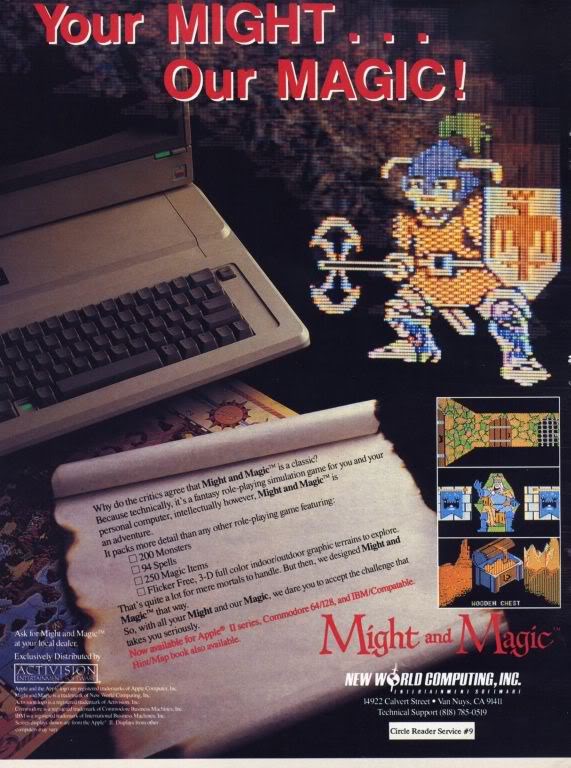

Out of his Los Angeles apartment in '83, Jon Van Caneghem's New World Computing — inspired by Wizardry, Ultima, and their Dungeons & Dragons roots — would spend three years programming and designing his brainchild with all of the features that he wanted to play with. The result was Might and Magic: Secret of the Inner Sanctum, and — like the games that inspired him — it would become one of the defining titles to toss alongside tile-based landscapes with first person, open-world exploration both above and below ground when it arrived in '86 on the Apple II.

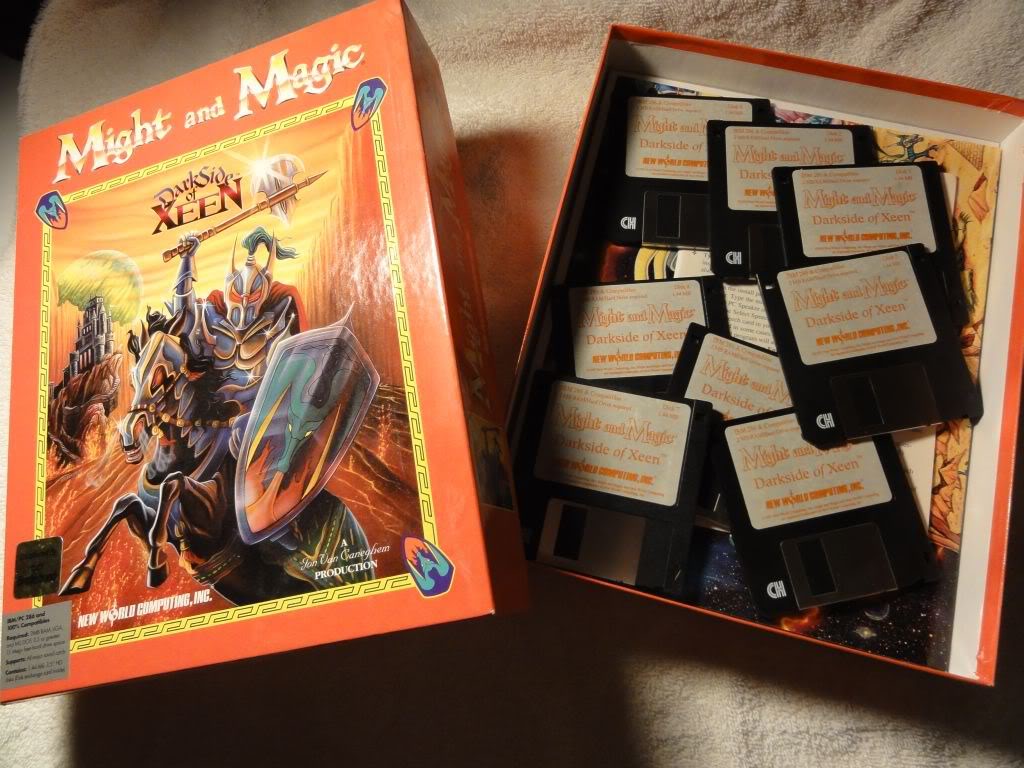

Might and Magic came packaged in a huge box filled with 5.25" floppies, a thick manual, fold-out map, and even a pad of paper with Might and Magic letterhead for notes and mapmaking. When I didn't have an app to duplicate the floppies for play (which was a requirement I wasn't aware of) and wrote the address on the back of the box looking for help, I received written letter from Caneghem with sincere apologies along with a batch of fresh copies that I can only guess he labeled himself.

That also says a lot about the passion of someone whose living room provided the line for customer service. Caneghem was a one-man marketing and distribution dungeon master.

The success of Might and Magic paved the way for what would become one of the longest running computer role-playing game series alongside Ultima and Wizardry. And they were tough. Although they didn't penalize the player in the same way as Wizardry, the game shifted the challenge over to the mobs of monsters, riddles, towns, and its deadly wilderness, which all provided more than enough ways to die in first-person bliss.

Simply living long enough in the starting town of Sorpigal to earn coin for food, experience points, and retain an ample amount of hit points to make it to the inn to save the game only provided a light preview for what was to come. And leveling wasn't automatic: You had to pay for each character's training to upgrade them.

The Might and Magic games were also consummate dungeon crawlers loaded with plenty of random encounters to keep feeding experience to your party. Many monsters could actually be bribed to leave your party alone, or the player could opt to surrender (and be stripped of gold and food while being moved to a more dangerous area) and hope for better odds later.

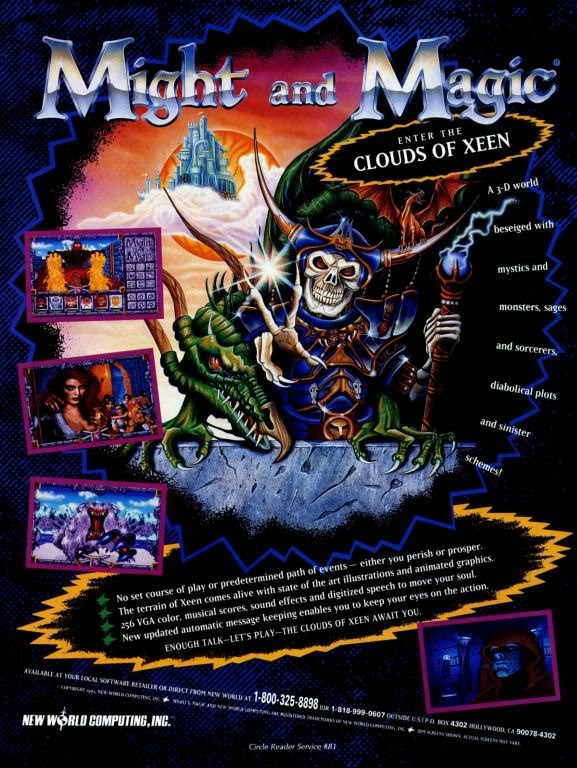

The series was also known for a sci-fi arc hidden behind the scenes. Although each game stood alone in the most basic sense, each ending would reference a story of revenge and later expand to hint at a great civilization that had once ruled the stars. In later titles, this tie-in would be much more explicit as adventurers armed themselves with ray guns and skulked through the ruins of forgotten technology.

Back in the eighties and early nineties, publishers went all out when it came to retail boxes. This thing is probably big enough to squeeze a MacBook into. Or a stack of iPads.

Might and Magic 4 and 5 (later released together as Might and Magic: World of Xeen) overhauled the graphics and gameplay of the previous titles, and here NWC flexed their creative muscles with the unprecedented feature of allowing both games to be combined into one world. This “World of Xeen” opened up a short quest and a new ending that left no doubt as to its sci-fi premise. Might and Magic 5 was like the ultimate add-on. And the boxes these two games came in? Massive.

Might and Magic 6 would overhaul the graphics engine yet again by the time it arrived in '98 (and toss out the grid-based movement of the previous games for free-roaming), but the series would find itself in competition with BioWare's Baldur's Gate as well as the growing popularity of new genres, such as first-person shooters, and the rising tide of the console market. Increased production costs had also begun to eat away at NWC's coffers.

Read on to page two for the story around these new challenges and the eventual outcome of NWC's flagship series.

NWC wasn't standing still, though. It had also ported a few of its games over to consoles, such as the first three M&M games, and like many of its peers, would also diversify into publishing and developing new titles. One of these was the turn-based strategy title King's Bounty in 1990.

King's Bounty would also set the stage for the other series that NWC was known for: Heroes of Might and Magic. The first game would arrive in '95, and the series would go on to entertain armchair lords and ladies through five installments with add-ons released for most of them.

It was also in '96 that The 3DO Company under Trip Hawkins bought NWC, injected cash into the company, and opened doors on what Caneghem had hoped would be Might & Magic Online. 3DO already had Meridian 59, so it did make sense to go with an established series for a new MMO — much like what Blizzard would later do with Warcraft.

It was also in '96 that The 3DO Company under Trip Hawkins bought NWC, injected cash into the company, and opened doors on what Caneghem had hoped would be Might & Magic Online. 3DO already had Meridian 59, so it did make sense to go with an established series for a new MMO — much like what Blizzard would later do with Warcraft.

But the partnership was a rocky one. With a new owner came new demands, one of which was to make NWC produce a new M&M and Heroes game every year.

From 1998 to 2000, Might and Magic 6 through 8 hit store shelves, one after another. Although M&M 6 was a lot of fun, M&M 8 began to show its age through an engine that had remained relatively unchanged since '98. The days of getting away with recycling the same engine across titles as the Gold Box series did in the late eighties and early nineties under SSI were over as far as the mainstream market — spoiled on the 3D craze for better visuals — was concerned.

Other troubles had also plagued NWC's legendary series — troubles that culminated in Might and Magic 9. Almost paralleling what had happened with Origin's Ultima 9, an unrealistic schedule and a rush to release doomed what would be the final game in the series under NWC's — and Caneghem's — name.

It received a critical drubbing, both in the press and by fans who tried to play this practically broken game. In an interview with M&M fansite Celestial Heavens, Lead Designer Tim Lang gave a no-holds-barred view on what went wrong. Part of the blame seems to have fallen on Caneghem's shoulders, though, how much of 3DO's own meandering direction had a hand in the product's final quality is still up for debate.

In the end, NWC had quietly faded along with its owner, The 3DO Company, in 2003. 3DO had declared Chapter 11 that year and then moved into liquidation. The series that had celebrated classic dungeon crawling and loot collecting with its vast worlds and endless mobs had ended with a bug-filled note. But it wasn't over.

Ubisoft had bought the Might and Magic name and resurrected the series with the action-oriented Dark Messiah in '06 (developed by the Arkane Studios, the makers of Arx Fatalis). Featuring class-based and leveled multiplayer along with a decent single-player experience, it was a solid game, though, a far cry from the turn-based CRPGs of its namesake. Clash of Heroes had come out in '09 for the DS, PS3, and the Xbox 360 as a surprisingly decent mix of puzzles and RPG gameplay.

The classic flavor of the series may have died, but the name lives on.

Shaking the Crystal Ball

Although the companies haven't survived or have changed so much so as to be unrecognized today for what they had once been, the passion and the drive of these developers during those heady days continues to influence and shape our hobby. Indies, such as Jeff Vogel's Spiderweb Software, have also kept the creative CRPG flame alive regardless of what the latest visual trend might be.

Many of the games mentioned in this series are no longer on retail shelves or easily found, relegating them to the niches of the 'net or in the hopes of those who want to see them offered on one of several downloadable services.

And not all of the games mentioned here have held up well over the years, though, a few are still entertaining enough to overlook the crude graphics and difficult controls. After all, the basic ideas haven't changed and there's still quite a bit of fun to be discovered without nitpicking the flaws of each one. Die hard fans have even gone on to update a few of these with emulation or total conversions of existing engines with incredible mods.

But they're also remarkable milestones that deserve to be remembered. And if there's one thing I've learned in my years of gaming, it's that there are always more stories to be told just around the next corner. Or wrapped in the shrouded history of the past.

For further reading, check out Computer Gaming World's 2004 interview with NWC founder Jon Van Caneghem.