This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Review scores have come under their fair share of scrutiny over the years. Many have claimed that any attempt to distil a complex opinion expressed over hundreds of words into a single number is inevitably going to lose a great deal in translation. Others take issue with the way publishers have reportedly been using Metacritic scores to determine a development studio's salary bonuses.

Numerical scores aren't going anywhere any time soon; they fulfill simply too many useful functions –chief among them being the automatic ranking of every game an outlet ever reviews. That being the case, would it not be beneficial to look at how scores can be improved, rather than simply threatening to eliminate them entirely?

For example, a review score is a very constant identifier of a game's overall merit, but as we all know, many games will waver in quality over time. Even the greatest games will trip up now and again, and even the worst will contain flashes of brilliance.

Let's start with a simple graph:

On the X (horizontal) axis, we have the game's playtime, and on the Y (vertical) axis, we have the game's relative score. Note here the use of the word relative. It would, of course, be ridiculous to claim that any review score has an absolute value. Thus, in terms of our charts, any position is given relative to those surrounding it.

So what categories would our favorite games fall into?

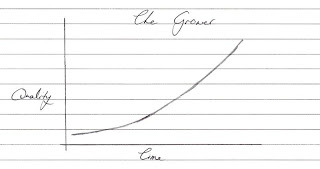

An obvious first choice is "The Grower." Its review graph is shown below:

As you may have guessed, a grower is a game which well…grows on you. It starts off a little slowly, perhaps by not explaining itself too well or maybe just bombarding you with unfamiliar gameplay elements. Over time, though, you grow accustomed to its mechanics and intricacies and end the game on a fantastic high.

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time filled this description perfectly for me. Since it was the first Legend of Zelda game I'd ever touched, playing through the opening areas was a little daunting. I didn't understand very basic concepts such as needing to use a dungeon's new item to defeat its boss, and I found its lack of hand-holding completely at odds with my modern gaming sensibilities.

As time passed, I began to lose myself in it. Dungeon layouts started to make sense, and I no longer needed to religiously run to Gamefaqs when an area stumped me. There were still moments of frustration as I progressed, but these all but disappeared by the time I came to rescue that poor Zelda.

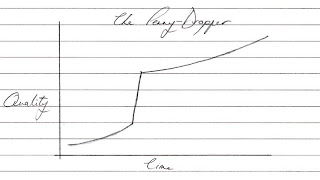

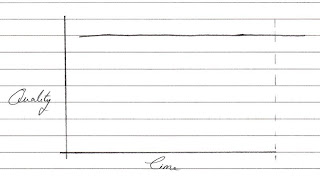

Similar to the grower is the "Penny-Dropper" shown below:

You'll notice that the general trend in the graph is the same, albeit far more severe. A penny-dropper is a game that all makes sense in an instant. Until that point it's very easy to give up and walk away with the knowledge that you made the right choice. You'd be missing out of course, as the second half of the graph so clearly shows, but that doesn't exactly make your decision wrong.

I can't help but think of Final Fantasy 13 when I think of this review graph, since it was unrelentingly mediocre for its first dozen hours. When the world opens up and the combat system is finally unlocked, the game becomes good, even great, but many die-hard fans agree that the first part of the game comes close to being not worth the trouble.

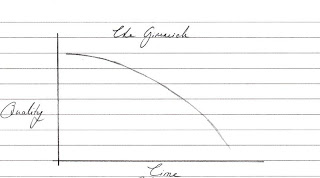

On the more negative end of the spectrum we have "The Gimmick." This is a game which bases its entire premise on a single mechanic, which it then manages to completely squander and run into the ground through sheer repetition. Here's a graph:

I think Fracture falls into this category without much contention. Few would argue that basing your game around the ability to raise and lower terrain is necessarily a bad thing. In fact, if Valve were to turn around tomorrow and announce its inclusion as a puzzle mechanic in Portal 2, you'd be utterly stoked to play with it. The problem with Fracture though was that – quite apart from the fact the rest of the game was beyond mediocre – it really failed to do anything new with this neat idea beyond the first level.

Fracture then, was a game based around a gimmick. A traditional review would give little credit to such a game, since clearly a reviewer is going to have very little of his or her initial excitement left by the end of the game. Does the initial idea deserve some credit though? Probably.

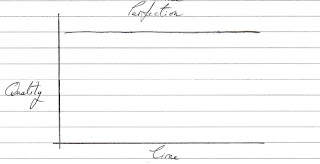

Graph-porn aside, there's an underlying question here that needs answering. What would the perfect game look like? You could claim that it would look a little like this:

You might even go a little further, and claim that it should leave you wanting more.

The truth is, though, that there is no perfect game. This is something that review scores have managed to magnificently ignore over the years. A score of 10 out of 10 carries so much weight and expectation that I'd be scared to even stamp it at the bottom of a page. A number requires so much justification on the author's part and so much interpretation at the reader's end. One man's perfect arc might be another's hump.

We try and claim that readers should make their purchases based upon the content of reviews rather than the scores, but this really ignores the reason that scores are there in the first place. Reviews are dense pieces of text, with multiple pieces of information within each paragraph. It's impossible to recite every pro and con of a game after reading a review, and then you have to consider the fact that you'll read dozens of reviews over just one holiday period.

Easy-to-parse summaries are an essential part of games journalism, but not because its audience is juvenile or stupid. There are far more factors which can affect your potential enjoyment of a game than you would consider when listening to the average music album.

So maybe, rather than dismissing the whole concept of scores entirely, we should be trying to work out how we can evolve them as a language. At the very least, we can use them as a means to think about our favorite games a little differently.

So what games do you reckon would fit into the categories I laid out above? Better still, are there any graphs I've missed altogether? Let me know in the comments below.