This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Roughly nine months. That's the amount of time it takes for a woman to give birth to another life. For a group of six students, this is how long it takes to develop a video game. In those nine months, the team has come to care for their project, Velisia: A Traitor's Legacy, about as much as a mother and father could for an unborn baby. And much like child care, a lot of hard work, preparation, and stress was involved.

Chris Wilson, the 26-year-old project lead of the student-developed game, puts the long nine months of work into perspective.

“There's very few university courses left that have a direct path into an industry, and sadly, this is one hell of a competitive industry,” Wilson said. “If you don’t work hard and have something to show at the end, it’s very likely that dream job just isn’t going to be there.”

That’s what these students attending Salford University in Manchester, a city in England better known for its soccer team that consistently dominates English football at Old Trafford, are hoping to achieve: dream jobs in the video-game industry.

“I decided to pursue a career in game development after a rather painful first career attempt in the high-street banking industry,” Wilson recalls. “Everyone always says 'pick a career in something you enjoy,' and that’s exactly what I plan to do now.”

The rest of his team also wants to do what they feel is a fun career: make games.

James de Silva, 21, went from studying mathematical physics to 3D art; Andrew Murray, 22, pursued 2D art for video games after enjoying drawing at a young age and dreaming of becoming a cartoonist; Rob Hatton, 21, helps with design; Mike Broster, 29, is an animator; and Matt Sanders, 25, is program lead.

Each has his reason for being at the school whether it is a needed career change or a creative outlet.

“I could have had a budding career in pizza delivery, so to avoid that fate, I figured I’d actually make use of the time I’d spent messing about on these programs over the years,” Broster said.

Sanders, like many, loved video games growing up.

“I was passionate about video games from a very young age, with a fascination regarding how games were put together both on a design and technical level,” he said.

Their passion, or lack of wanting to be delivery boys, has led them to their final year of the Computer and Video Game Design course at Salford University. Courses at the college are what one would expect for game development.

“The first two years of the course are designed to develop students’ skill sets,” Wilson said.

At Salford, undergrads become more specialized as their time at school progresses, and they get a lot of hands-on and practical work in video-game design. A small team project is completed at the end of the second year, and a main, final project takes up most of the third and final year.

The courses also provide lectures from video-game developers, such as Smash Mouth Games, plying their trade at Manchester, which gives students a professional look at development.

Started in 2000, the program Wilson and his team are in is actually one of the oldest in England. Salford’s game-development courses will actually grow as they become a part of the university’s MediaCityUK, a place where over 1,500 students and even more industry workers will come together in a community meant to help promote creativity, learning, and collaboration.

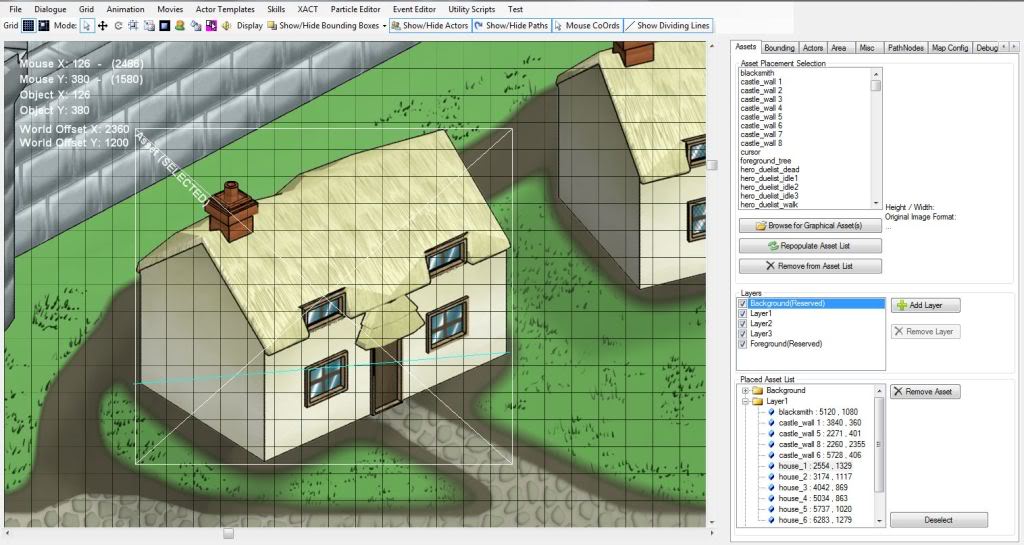

No matter where the program heads or how much it grows, there is but one main focus of the course track for aspiring programmers and artists: to simply make a game from scratch.

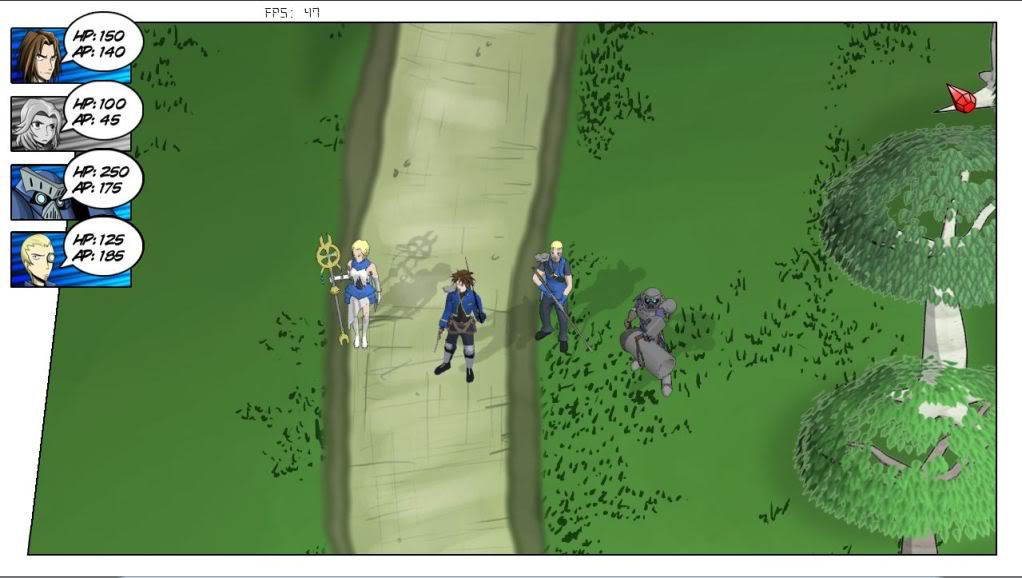

This is how Velisia, a turn-based strategy game modeled after Advance Wars and Final Fantasy Tactics, came to be.

The player will take command of a squad of four unique Velisian soldiers who are heavily outnumbered as they fight an evil thought to be extinct as civil war erupts; players must use these soldiers' abilities to their greatest potential to overcome their enemies.

The project has been quite the eye opener.

“Before doing this course, I could only have guessed just how many man hours it takes to produce a video game,” Wilson said.

Much of this time came with the many hours needed just to polish, refine, and tweak the project to a finished and playable state.

“During these tasks, people become very stressed. Friendships between team members have had to be delicately handled when you desperately need more work from a team member but don’t want to cause a fight,” Wilson said.

Velisia, like any game, has been through quite a number of changes. At first it was going to be created with the Unreal 3 engine with a third-person view — something that quickly became unrealistic with the mechanics created for the game and only one programmer and six months to work with.

“We were forced to choose between changing our game engine to XNA framework, with which the programmer was more comfortable, or making sweeping sacrifices and simplifications of some major game mechanics,” Wilson said.

“We chose to preserve the game mechanics we had put in place and sacrifice the advanced engine under the general principle that good game mechanics are more important to game design than some of the capabilities of modern game engines,” Wilson added.

Choosing an engine was just the beginning. One of the major changes to the game was switching from animated sprites during character-ability attack animations to fully animated videos of the 3D models.

“Not only did this change allow us to show off the models in a much more dynamic fashion, but it allowed us to develop the game further towards the anime/manga inspiration we had been drawing on,” Wilson said.

Before that, the game had many drawing comparisons to Valkyria Chronicles and Final Fantasy Tactics. Velisia now has a unique personality.

Many changes and tweaks came from the professors giving real-world feedback during reporting sessions. These sessions are both rewarding and gut-wrenching for the students.

“During these report sessions, we would receive feedback on all of our work from the tutors, and on the weeks that things had gone well, it was always extremely rewarding to hear some praise for our work,” Wilson said. “The good weeks, however, were few and far between as the tutors ensure that their comments are as true to the industry as possible.”

After all the hard work, hours, numerous revisions, and sleepless nights of programming fueled by caffeine, Velisia is something to be proud of.

“Seeing the game evolve from a glint in a developer’s eye to something tangible is without a doubt the most rewarding part of the development process,” Wilson said.

The team hopes to eventually release Velisia for retail sale. The game, jointly owned by the university and students, will be assisted in its commercial release by Salford if the team deems it their next goal.

“Although the original goal of the Velisia project is — and will remain to be — a university module assignment, we are looking to release the game for sale at a later date and have already received emails of interest in retailing our product from several distributors such as Gamersgate.com,” Wilson said.

And while the goals most watched and celebrated in Manchester are from the Red Devils at the Theater of Dreams, this six-man team’s goal of making an impact in the video-game industry may come to fruition as Velisia becomes their very own gateway to their own dreams and ambitions.

Photos from top to bottom: Project lead Chris Wilson, animator Mike Broster, and a caffeine-fueled Rob Hatton.

Go here to see the game in motion.