This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

In his latest Editor’s Note, Escapist Editor-in-Chief Russ Pitts takes umbrage with GameStop for used-game sales, with the implication being that GameStop puts its own self-interest above the state of the industry. Presumably, gamers are the enablers allowing the charade to continue. To which I say, so what?

Russ’ droll, satiric commentary echoes a sentiment expressed by developers, publishers, and critics alike — that retailers and consumers have a moral obligation to support the industry. Yet the ethical responsibility of both extends no further than enlightened self-interest.

“If only they'd [Gamestop] realize they're a dinosaur and lie down and die already, they wouldn't be stuffing their shelves with pre-owned merchandise, selling used discs for mere dollars off the price of new, cutting into publisher profits, and eroding the lifeline for struggling developers,” kvetches Russ.

I feel he fundamentally misunderstands the nature of the free market.

Consumers’ primary stimulus is attaining the best (perceived) value for their money. Altruism doesn’t figure into the equation. So, environmental activists won't convince a sizable majority to buy hybrid cars under the impetus of “saving the planet” (long-term value vs. short-term investment is a more viable tack). Similarly, the rationale of “supporting the industry” won’t inspire the masses to spend more on games than they have to. Most people will seek the best deal, irrespective of moral considerations. Nor should they feel obligated to serve any higher cause.

As long as they obtain the games legally, I see no problem with bargain hunting or alternatives to buying new. If gamers would prefer to save a few bucks, they should feel no compunction about purchasing used. If they’d like to borrow a friend’s copy, that’s their prerogative. Gamers don’t owe the industry anything and vice-versa. The gamer-industry relationship is strictly business related. It begins and ends when money changes hands.

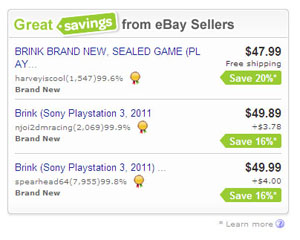

Should consumers therefore feel obligated to “support” their chosen hobby? Take Brink, for example. Must gamers feel obligated to spend $60 in order to show their allegiance to the industry and provide financial support? A cursory search on eBay revealed a deal for $47.99 (plus free shipping). Should I feel guilty about saving $12? The answer to all these questions is no.

Some feel that GameStop’s excessive profit on used-game sales is immoral. But who gets to decide how much profit is morally acceptable? Should we regulate the price of used games? And upon whom do we place such an onus? The industry? The government? This line of inquiry leads us to a very ugly place. Here’s something else to consider: If we reduced the price of used games, the industry would whine that we’re making their purchase more enticing. The only way to solve this problem is to eliminate the secondary market, and that’s an absurd proposition.

To take my eBay analogy further, is it immoral for collectible dealers to turn outrageous profits on baseball cards or beanie babies? I see no difference between individuals hawking their wares on the secondary market versus corporations doing the same thing. The argument that a multinational corporation, such as GameStop, has lots of money and isn't entitled to the excess profits that used-game sales generate is specious at best.

Despite the industry’s protestations, the legality of the secondary market is not in dispute. I quote from Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 109 (i.e. the “first-sale doctrine”):

“The owner of a particular copy or phonorecord lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy or phonorecord.”

Amazon's, eBay's, and GameStop’s used-game departments (among other secondary sources) fall under this statute. Developers and publishers have no right to a cut of the profits past a game’s initial sale. The industry is desperately pining for the veritable “all-digital future” so they can control all means of distribution, thereby eliminating the secondary market. In the process, we risk losing fundamental property rights.

The Xbox Live Marketplace ties purchases to your account, so if you switch game consoles, you must be logged in to redownload your content. No internet access means you forfeit your downloads. The PlayStation Network (when it’s up) restricts downloads to up to five consoles. In the case of OnLive, your “purchases” are actually extended rentals.

Don’t get me wrong — retailers aren’t sterling angels. When I worked for Electronics Boutique years ago, we’d shrink-wrap returned games (in new condition) and resell them. Juxtaposed with the perceived benefits of buying new over used, this was morally vexing. But the elimination of new-game returns (owing to retailers’ self-interest) put an immediate end to this thoroughly despicable practice.

Still, I’ll take retailers and their occasional moral failings over the industry’s vision of somnambulant gamers swallowing whatever’s fed to them and an all-digital future where we don’t own what we purchase. I love video games, but feel no need for reciprocation. I “owe” the industry nothing. Beyond obtaining my games legally, I feel no sense of obligation. If that means I don’t “support” the industry, then so be it.