This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

No game or movie can ever recreate the terror and intensity of actual combat, but there’s something to be said for a noble failure. Whereas lots of modern war movies strive for realism, first-person shooters always just aim to entertain. It is because of this singular focus that your average FPS tends to resemble the work of Michael Bay: a loose collection of shootouts and explosions. By way of comparison, the movie Saving Private Ryan captures not only the visceral intensity of combat, but the emotional toll it takes as well.

Gaming is capable of doing so much more as a medium, if only people would realize that there are other templates for success than hackneyed action flicks.

In the interest of full disclosure, I briefly served in the military from 2005-10, so I’m probably biased. I was never “in the shit," nor have I ever experienced combat firsthand, but it doesn’t take John Rambo to smell the BS wafting from most FPSes. Developers and gamers zealously defend the genre against charges of exploitation, but when the games make no attempt at realism, it’s hard to see them as anything but.

Gaming is still a very technical medium; built upon simple diversion and with little regard for narrative, it has struggled to evolve. Did Tennis for Two have a professional screenwriter? Did Spacewar! adhere to the standard three-act structure? Did Pong end on a cliffhanger? It’d be difficult to classify these early efforts as anything more than games, because they really were nothing more than cheap sources of amusement. “Story” was an entirely peripheral concept, and I would argue that modern video games have made little progress.

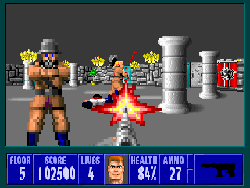

In the time since Wolfenstein 3D — often considered the original first-person shooter — these games have gone from glorified shooting galleries to technical marvels. Texture mapping, advanced motion-capture, and the ubiquitous Unreal and Call of Duty engines create sharp, photorealistic graphics. Sampled weaponry and military consultants make the “suspension of disbelief” an easier pill to swallow. Modern FPSes look and sound authentic, but in the process, we’ve neglected the intangible aspects of war — the intensity, fear, and crushing sense of finality. There’s no agenda or higher calling beyond pure entertainment.

In the time since Wolfenstein 3D — often considered the original first-person shooter — these games have gone from glorified shooting galleries to technical marvels. Texture mapping, advanced motion-capture, and the ubiquitous Unreal and Call of Duty engines create sharp, photorealistic graphics. Sampled weaponry and military consultants make the “suspension of disbelief” an easier pill to swallow. Modern FPSes look and sound authentic, but in the process, we’ve neglected the intangible aspects of war — the intensity, fear, and crushing sense of finality. There’s no agenda or higher calling beyond pure entertainment.

Take this scene from the 2001 film Black Hawk Down: The battered convoy heads back to base, with Somali militia taking potshots at them along the way. Suddenly, a shooter hits the lead Humvee’s gunner, SGT Dominick Pilla, who slumps out of the turret and lands right on his buddy’s lap. The camera cuts between different individuals as they take in Pilla’s untimely death, but our grief is short-lived. As the music swells, another soldier mans the .50 cal and suppresses the remaining enemies.

The gaming equivalent goes something like this: With little pretext, you get into a .50 cal turret and proceed to mow down hundreds of bad guys. That's it. There’s no emotional investment, no sense of gravity. There’s little beyond the actual act of killing. Dead comrades are brushed away, each soldier a mere blip on the screen. Many shooters, like Ghost Recon: Advanced Warfighter 2, actually encourage you to recklessly sacrifice comrades. Why would the player feel any trepidation about losing squadmates when they’re nothing but war-movie clichés?

Black Hawk Down’s purpose is to showcase the heroism of the Rangers and Delta operators who acquitted themselves admirably on that tragic day. What’s Black Ops’ reason for existence? It’s certainly not to inform — there’s no attempt made at realism beyond superficialities. The underlying subtext and human emotion is stripped from the experience. What’s left is a crass imitation of popcorn action flicks. I'd even say that Saving Private Ryan’s first 20 minutes are more authentic than the entire history of first-person shooters.

It’s hard to take FPSes seriously when their narratives toe the line between absurd and ridiculous. Realism is swapped for neo-commies, shadowy government conspiracies, and nuclear missile strikes. Developers are so horrified of making waves by featuring contemporary conflicts and enemies that they substitute in cartoonish Russians, Nazis, and zombies. Any game that attempts to cloak itself in realism is met with a chorus of boos, and who can blame these indignant critics? Gaming doesn’t have the greatest track record when it comes to nuance and subtlety.

It’s hard to take FPSes seriously when their narratives toe the line between absurd and ridiculous. Realism is swapped for neo-commies, shadowy government conspiracies, and nuclear missile strikes. Developers are so horrified of making waves by featuring contemporary conflicts and enemies that they substitute in cartoonish Russians, Nazis, and zombies. Any game that attempts to cloak itself in realism is met with a chorus of boos, and who can blame these indignant critics? Gaming doesn’t have the greatest track record when it comes to nuance and subtlety.

When Tom Clancy’s The Sum of all Fears was adapted to film, the villains were changed from Arab nationalists to neo-fascists. FPSes followed suit, dropping any realistic enemy combatants for more imaginary enemies. Halo gets a pass, because it’s set in a fictional, sci-fi future. But what’s GRAW’s excuse? Why does Modern Warfare 2 eschew contemporary conflict for Red Dawn?

The newest Medal of Honor is a huge step forward, both for the genre and for gaming in general. MOH is set in Afghanistan, circa 2002, during “Operation Anaconda.” Its narrative adheres closely to the book Robert’s Ridge and as such, carries the whiff of realism. I was very impressed with how authentic it felt, but many actually criticized the writing for being too wooden. That's the thing, though. The real Tier 1 Operator isn’t Nicholas Cage or Sean Connery from The Rock. Every word out of their mouths isn’t worthy of Shakespeare. They’re just regular guys with extraordinary skills and courage. Plus, the ending of Medal of Honor just floored me. Instead of the usual bombast, they close with a sincere tribute to our Special Forces.

There’ll always be a market for dumb action flicks and shallow FPSes like the Call of Duty series, but for gaming to move forward as an artistic medium, developers must strive for greater realism. FPSes can, and should, express more than just death and destruction.