This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

SPOILER ALERT. You've been warned.

Hindsight is 20/20, but in Chrono Cross's case, so is plain vanilla "sight." Even on release, as the title earned critical acclaim and mountains of praise, any thoughtful analysis of its combat system and pointlessly meandering narrative reveals a lackluster but very pretty game. Said prettiness, along with being the sequel to the beloved — and mad overrated — SNES hit Chrono Trigger ensured Chrono Cross its place in the hearts of JRPG lovers anywhere. Too bad it doesn't even remotely deserve it.

Insert bad pun about Guile's theme being uplifting. Did you know Guile may or may not be Magus? Yeah, I don't care either.

Contrary to popular apologist defensiveness, Chrono Cross's cringe-worthy story isn't terribly difficult to follow or understand; just needlessly complex and a mouthful to explain.

Remember Belthasar, one of three Zeal wise men who was transported to the post-apocalyptic future during the Ocean Palace incident? Well, thanks to the efforts of Crono, Lucca, Frog, and company, he found himself in the Lavos-free future, where he used the advanced technology at his disposal to learn that Lavos wasn't actually destroyed, just banished to the nothingness beyond time's flow. Schala, Zeal's princess and Magus's older/younger sister, was taken to that nothingness herself, and soon Lavos started "merging" with her, somehow creating the "Time Devourer," a creature capable of devouring space-time.

Belthasar, who you may remember created the Epoch from the last game, created an artificial archipelago called El Nido, with a technological institute called Chronopolis at the center. Designing it to engineer a "time crash" in 2400 AD, Belthasar takes another Epoch to 1020 AD, to see El Nido now existing in the world. Said time crash propelled El Nido and Chronopolis backwards in time to 12,000 BC, the time of Zeal, all with the intention of, circa 1020 AD, empowering Chrono Cross's main character Serge to free Schala from Lavos's grasp. But the planet — or Lavos, I don't know — brought Dinopolis, an alternate reality Dragonion city — the Dragonions being Reptite descendants in an alternate reality where Azala won — to the "regular reality" to act as NO MORE STOP IT AAAARGH MY BRAIN GAWD.

Storytelling 101: less is more. Poorly applied ambiguity and unnecessary complexity runs rampant in wildly overrated Japanese writer Masato Kato's works, from Chrono Cross to Xenogears to the recent waste of 18 hours of my life known as Sands of Destruction. When used correctly (see: Inception), ambiguity fleshes out a narrative, adding intrigue and promoting thoughtful interpretation. When used incorrectly, as is the case in Chrono Cross, it serves merely to mask a writer's inability to form coherent, compelling characters and settings.

The whole story comes across as Kato's ego trying to take ownership of the Chrono series, something he's wanted since he penned the era of Zeal in the original game. Chrono Trigger's various eras were written by different authors, and apparently development of the game was a mess. It feels as much when played through, if one pays attention, but even so, Zeal is where the tale throws you a curve ball. What started as the story of a boy and his friends accidentally discovering the far off apocalypse and meeting allies across the ages becomes a fuzzy haze once 12,000 BC comes into play. Kato didn't want to change his part of the story, which eventually led to him being credited as Trigger's scenario writer and Zeal being infused into every era, dominating the story from beginning to end.

Chrono Cross continues it. Everything about this game's story is Kato reminding you that Zeal was his favorite pet; the entire story serves to tie up a Zeal-based loose end. Which in and of itself isn't wrong, if the concept were handed off to someone with a much better idea of how to write and implement this sort of story, and given free reign to chop away the abundant bloat. Oh, and there's no shortage of bloat: 44 party members, only two important to the story, and of those two, one spends more than half of the game in the main villain's body and the other is just absent.

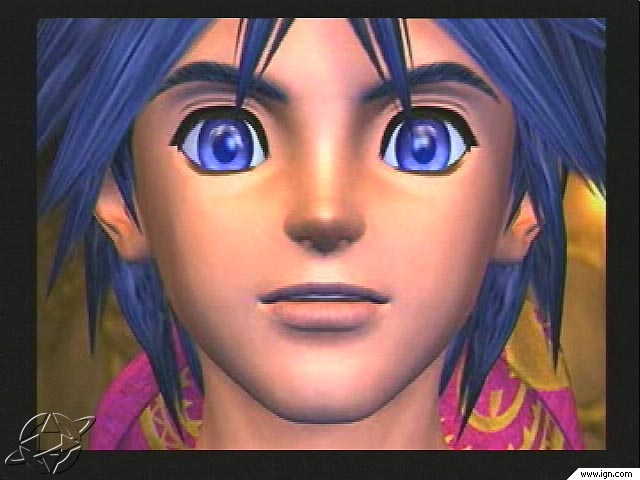

Serge may or may not be any of the following: the Chrono Trigger, the Arbiter of Time, the cause of Lavos's (re-)emergence in 1999 AD, his own father. I'd look perplexed too.

But that hypothetical scenario crafter was never contacted. Instead we get a story that's slightly worse than high school fanfiction, using tangents and virtual smoke and mirrors to mystify the audience, hoping it will fool them into believing they're watching the stuff of high art. It's apparently attractive bait, if the critical reception and fond memories of Chrono Cross to this very day are any indication.

Despite all this, solid gameplay can overcome even the most ludicrously horrible of plots, right? Surely, Chrono Cross learned a lesson from its predecessor, incorporating scripted, unconventional boss encounters and the massively fun dual/triple tech system, yes? Nope; Chrono Cross's combat system is almost as pointlessly puzzling as the story. It tried to be about strategic use of stamina, forcing the player to use accurate but weak attacks in order to build accuracy for heavier hits and the resources to use "elements" — spells and abilities forming the cornerstone of a customizable skill system. Every character has an innate elemental color, one of six, and is better suited towards using elements of that color. Dual and triple techs are rare, and with 44 characters it's frustrating to find out what few elements lead into those combinations without a trip to Google.

Unfortunately, it ends up being unintuitive and the not-in-the-good-way sort of challenging, forcing players to either irritatingly study the various entwined mechanics or just grind their way to overlevelling content and physically attacking their way to victory. When things work out, they feel good; when the Dragon God, who may or may not be the Time Devourer — excuse me as I smash my face into a wall repeatedly — shifted to the elemental color blue, the red-aligned X-Strike hit him for impressive four figure damage that admittedly got a laugh out of me. Every other time, it's a chore. Especially if you accidently choose the Run Away option, which works in every fight (resetting boss health) and doesn't prompt for confirmation.

Take that! You better hope I accidentally flee for my life after, scum who may or may not be relevant to the overall plot!

Managing 44 characters is no picnic. Since your active battling party consists of three characters, avoiding excessive micromanagement involves picking your three favorites, sticking only to them, and hoping the story doesn't take them away from you.

Not much more needs to be said. The game is visually beautiful, showing off PSX potential, and features a hauntingly lovely Celtic-ish soundtrack. Cutscenes are pretty affairs, and indeed comprise some of Chrono Cross's least irritating moments. Memorable ones include Serge, in Lynx's body, roaring in grief when now-fake Serge stabs Kid, and the entirety of the area called The Dead Sea, a mishmash of the bad future areas in 2300 AD from Chrono Trigger.

But looking good and sounding good, that's just not enough. Gameplay matters most; Chrono Cross handles this ineptly, turning interesting ideas into a convoluted mess. Such a story-driven game needs way more competent scenario writers and world/character crafters than Masato Kato, whose application of ambiguity, and overall storytelling ability, is laughably amateurish. As a sequel to the overhyped-but-still-good Chrono Trigger, Chrono Cross fails to deliver.

That it claims so much undeserved love and respect is unfortunate… and a little troubling.

Screenshots from IGN's archive.

Carlos Alexandre is a self-described handsome fat man. He ponders his entertainment, and you can find said ponderings on both his website and the podcast he co-hosts.