This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

It has been years since I took to the stars with the first Starflight on the Genesis.

It was out on PCs first, but all I had was an Apple so I missed out the fun until it was ported. But its sequel never made it over and by the time of blast processing, was difficult to find when I finally had my own IBM PC. In those days before Ebay and Craigslist, getting ahold of anything that old was left to the tender mercies of bargain bins buried at the back of brick-and-mortars. And even then, it was still a crapshoot.

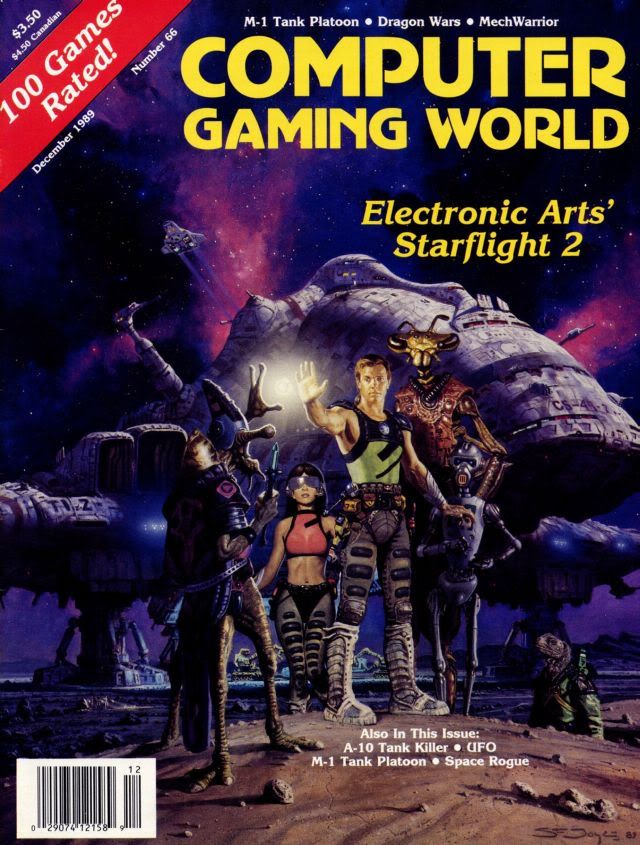

My friend with an IBM PC, on the other hand, gushed all over both. If I couldn't play either one, at least I could live vicariously through his tale telling. The flashy ads, CGW's preview from December of '89, and cool box art tantalizingly teased a universe of adventure and open ended gameplay.

This is also the boxart for the game. I like the theory that boxart had to be

so incredibly awesome in those days to make up for what the

pixels couldn't do. Or maybe the artists were just that excited about

the game.

The first Starflight earned a place in CGW's “Hall of Fame” and accolades from a number of press outlets back in the day. Starflight 2 had also made the rounds, but while it might not have been as revolutionary as its predecessor, it offered more on top of what the first game had done despite not being as unique. These were two star traveling operas whose mechanics would serve as inspiration to titles such as Mass Effect and who shared peer space with others such as Elite.

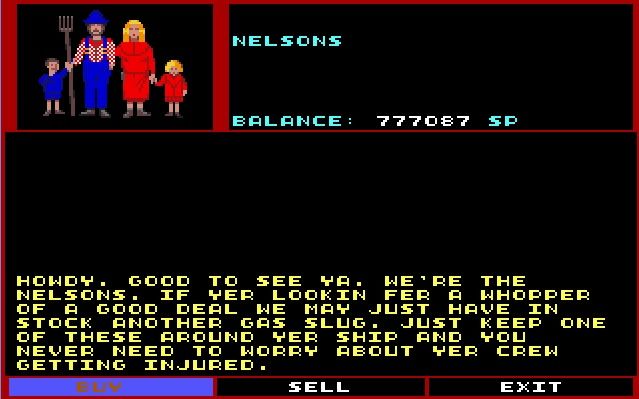

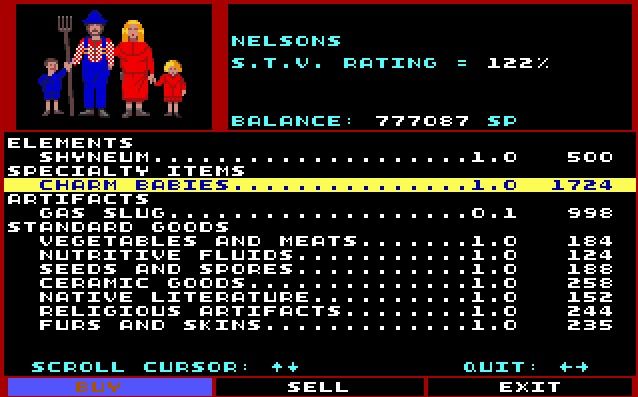

Now, nearly more than two decades later, I've finally traded Charm Babies with talking dinosaurs named the Djaboon, got my crew high on a gas slug, adopted a depressed Dweenle as my engineer only to hear him complain that everyone hates him, slugged it out with spineless Spemin turned galactic bullies, and saved the known universe by traveling back in time.

I also have a notebook crammed with hastily scrawled coordinates and hints, snippets of conversations, and lines drawn everywhere linking scattered clues together as if I were living out the wall that Robert Downey Jr.'s Sherlock Holmes had assembled from his obsessive quest to unravel the mystery behind A Game of Shadows. He and I were on a mission to save our respective worlds.

Only in mine, there were lasers, space ships, and aliens.

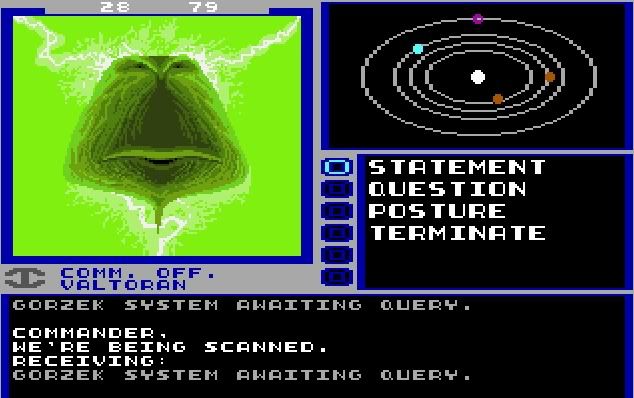

Making new friends was always a momentous occasion as long as

they weren't trying to kill you.

Where did it come from?

Binary Systems, the devs behind the first Starflight, created the sequel and EA published it in 1989 for MS-DOS PCs. It was later ported in '91 for the Amiga and the Macintosh. After those halcyon days, it and its predecessor wandered in bargain bins and eventually found themselves lost among abandonware sites online for years afterward.

I'm not sure if it ever appeared as part of any collection since then as physical copies became more difficult to hunt down outside of then up-and-coming sites such as Ebay. And now more recently, to the surprise of many, it re-appeared in an official capacity as a bundle on Good Old Games on November 24, 2011, complete with PDF copies of the manual, hint guide, and a handy starmap. Cool!

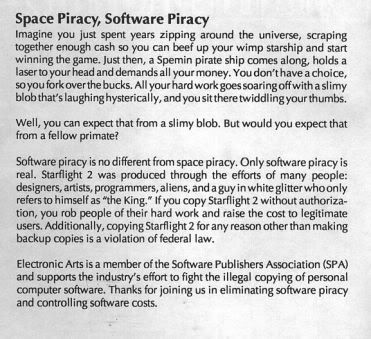

Interestingly, the PDF manual that comes with Good Old Games' copy of the game omits the amusing "anti-piracy" message that came with it along with the software license at the back. This was probably to avoid any legal issues, though here's a shot of the missing anti-piracy message for your entertainment:

Piracy was as much a problem back then as it is today.

Also, one probably couldn't get away with saying this anymore.

To the stars…and beyond!

Starflight 2 built on top of what made the first game fun. The back box cover boasts over 500 planets and thirty alien races, six of which also have ships of their own and not all of whom were happy to see you. A twisting storyline, plenty of space to explore, and diplomacy wrapped everything together. All of this originally fit on two single-sided 5.25 floppies for the IBM PC which makes it smaller than most Xbox Live patches. Or Angry Birds.

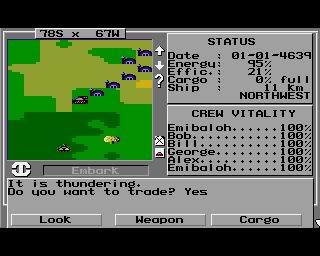

It's not much on looks, but not knowing what was on the surface

called to my inner Kirk. Or was it Chekov? At least I wasn't a red shirt.

Okay, I'll stop now.

Many of the mechanics behind Starflight 2 hold up even today. They have to, especially if you're a stickler for graphics. The Amiga version, in particular, sported far better visuals over its VGA counterpart though the back of the box featured screenshots from the IBM PC version. The Good Old Games version is the one for the IBM PC.

This is what players saw on the IBM PC. And, oh look! MacGyver is still alive

in this save game. Yay!

And this is a shot from the Amiga version. Pretty!

Slingshot Around the Sun

Starflight 2 takes place some time after the first game though it isn't necessary to play that to get the gist of what is going on. The Spemin, the antennae'd blobs who talk big but were cowards at heart, have now become a Scary Galactic Threat ™.

Badass on the outside, soft and cowardly on the inside.

Somehow, they have acquired powerful weapons and shields that work in nebulae and have threatened your home of Arth with ultimate destruction at the hands of THE SPEMIN DEATH FLEET (their caps).

Whether or not such a fleet exists isn't the point. How they have become so powerful, and have access to an unlimited amount of fuel, is. Eventually they'll find the courage to follow through with their threat so before that happens, you need to find the source of their technology, seize it, and put an end to their plans.

Despite the threat of a SPEMIN DEATH FLEET, there is no time limit. The game cuts you loose inside a space sandbox from start to finish leaving it up to you to follow whatever leads you find interesting. If you wanted to shoot at everything, nothing prevented you from setting your mission to kill – just don't expect to finish the game or survive without help for very long. Being a galactic ass has few rewards in this game.

If you just wanted to fly out there and check out things for yourself, you were free to do that, too! Only there was this little thing called “Shyneum” which acts as your fuel. Running out of it didn't necessarily end your mission, especially since you could call for help, but don't expect to get off without a fine for neglecting to top off. On the other hand, it's handy to have if you survive the battle but have your engines blown out at the last second.

The first order of business is to get a crew together. Unlike many other CRPGs, this one allows you to generate a crew from a number of alien species and pay for their education right at the start. It's tempting to max everyone out with the cash you have on hand, though best avoided if you still want to be able to put gas in the tank and trade for anything more than seeds.

There's quite a bit of tongue-in-cheek humor in Starflight 2 to lighten

up having to save all life as we know it from extinction.

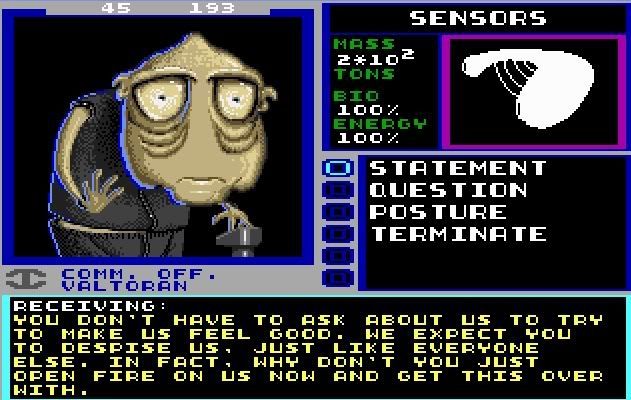

Yet, it's also key to at least get a few trained up to avoid embarrassing mistakes. A skilled Navigator can give you the coordinates of space you're in right after jumping through a wormhole to avoid getting lost. A trained Communications Officer will be able to display more than gibberish when talking to your neighbors.

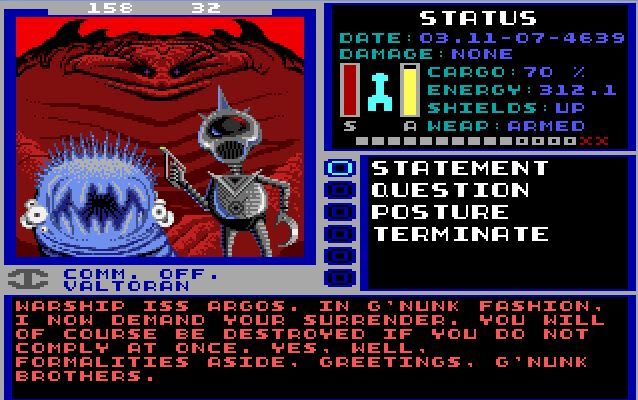

And it's the aliens that make the art of diplomacy, and your posture, a lot more important than your aim be it Friendly, Hostile, or Aggressive. Being Hostile with everyone was the surest way to becoming space dust, though with the G'nunk, it's expected before they decide to kill you as a favor for being weak. Aliens didn't like waiting around, either, and would occasionally wonder if you were going to say anything or simply decide to leave if you just sat there.

These guys are in permanent 'roid rage mode. They tend to shoot first and

never ask questions later, though they might collect your ashes to use

as handwash grit.

Trade is also at the heart of the game. Starting out with only a small amount of cash in an unknown sector of space, finding out who wants what without running out of fuel led to a few false starts until I finally found a route that worked. Bartering for a better price on everything was also added an additional layer of the unknown. Pushing a prospective customer only so far walked the fine line between getting a huge bonus for your goods or pissing them off entirely and having them refuse to buy it. Period.

Talking with the different alien races floating about in space, grilling them for info, and bringing them special treats, had also dropped pages of notes into my lap. Not only did the aliens appear very alien, they were fleshed out with deep layers of text to give them character. Flying to the ends of space just to hunt down more to talk to kept the explorer in me busy for hours on end.

The Dweenle. Just inserting this snapshot is making me depressed..

No Hand Holding

There weren't many creature comforts built in. Saves, at least in the Good Old Games version running under DOSBox, are handled in a simple menu that didn't ask you if “you were sure” every step of the way. No auto saves here. Only so much could fit on those floppies making this a very hands on experience.

Keeping track of clues was made a little easier as you could replay dialogue read from each race, though due to limitations at the time, you had to scroll through all of the entries to find the one you wanted. It was often easier to just write down hints and reference it the old fashioned way. At the same time, this also made solving the open ended quest highly dependent on how good a note taker I was (and thankfully, not because of my handwriting).

Trading made exploration that much more exciting. I couldn't help but search out distant worlds on the included starmap for races that might be willing to give up a few precious items – along with some Shyneum for my ship – that someone else might desperately need. Sometimes this even made certain artifacts available to me after I proved myself a 'decent' trader.

But the same trick that could stuff hundreds of worlds on these disks had also made it tedious business from time to time. A procedural method was used to generate each world with a few hard coded locations pertaining to the story. Using this was the equivalent of having in-game cinematics – it saved a ton on space without compromising the appeal of the game. In this case, having a huge variety of worlds to mine for ore and explore.

The problem was that the trading posts were sometimes as random as the landscape, on occasion changing locations after leaving a planet and returning later. Since you couldn't scan for trading posts from orbit, you had to search them out at random leading to a lot of wandering around that was boring as hell.

There wasn't a whole lot to these planets when it comes down to it – only the idea that there might be something special outside of the story lurking on one outside of the beaten path. Sometimes there was, but only if another race let you know that there was something worth finding on a particular world. When rumors and hearsay hinted at these special places, the potential for the game re-asserted its Kirk-like visage.

Or unless you loved to collect lifeforms as a spacefaring poacher.

Set Course for Home

Discovering my first successful trade route, giving my ship some needed teeth, and meeting all sorts of strange beings while digging into the past all appealed to my inner adventurer and made it easy to see the parallels drawn between the Starflight series and other titles decades later such as Egosoft's X series and BioWare's Mass Effect. Even the note taking gave the experience a tactile aspect – and made it easier to appreciate the development of in-game journals.

The emptiness of most of the planets in the game was a minus if only in hindsight. Until I reached the end, simply knowing that there could be so much more out there awaiting discovery was as much an impetus to play as the storyline.

The impact of having a well trained crew on my side affecting things such as simply being able to talk to another race, finding my bearings in space, or whether or not a planet would crush me with its gravity if I decided to touch down for a visit, could never be underestimated and added a degree of uncertainty at the start. Once I figured out what I needed, my survivability was as much a reward as it was in landing that first deal.

Other pieces are also reminders of a very different time. The manual alone starts off with pages of in-universe fiction along with some hints as to what to do first as there was no in-game tutorial. The pixelized surfaces of its worlds and the icons running about tested the imagination aided by drawings of eight legged rhinos and bronze harpooners on its last few pages. A starmap was required to get through the game as well as its copy protection. Failure would mean that several game days later, an interstellar cop would show up in the game to end it for you.

Not every game ages gracefully. Audiences can often outgrow that which they had started with and this game is no exception to what certain mechanics today have polished.

At the same time, while there's no question that as “hardcore” as it is in certain respects because of what the gameplay lacks, the same gameplay drops as much responsibility into the player's hands as the real captain of this particular enterprise. And that's one lesson that should never be outgrown.

Combat was sometimes unavoidable. Arming shields and fighting with missiles while circling around enemies was basically the only tactic I used, though survival was a far different matter early on when my ship was about as intimidating as a Constellation-class pinata. But, after enough trades, I could finally trade a few shots and take down even the Spemin.Staring Through the Retroscope – Starflight 2

It has been years since I took to the stars with the first Starflight on the Genesis. It was out on PCs first, but all I had was an Apple so I missed out until it came out on consoles. But its sequel never made it over and by the time of blast processing, was difficult to find. In those days before Ebay and Craigslist, getting ahold of anything that old was left to the tender mercies of bargain bins buried at the back of brick-and-mortars. And even then, it was still a crapshoot.

My friend with an IBM PC, on the other hand, gushed all over both. If I couldn't play either one, at least I could live vicariously through his tale telling. The flashy ads and cool box art tantalizingly teasing a universe of adventure and open ended gameplay didn't help.

The first Starflight earned a place in CGW's “Hall of Fame” and accolades from a number of press outlets back in the day. Starflight 2 had also made the rounds, but while it might not have been as revolutionary as its predecessor, it offered more on top of what the first game had done despite not being as unique. These were two star traveling operas whose mechanics would serve as inspiration to titles such as Mass Effect and who shared peer space with others such as Elite.

Now, nearly more than two decades later, I've finally traded Charm Babies with talking dinosaurs named the Djaboon, got my crew high on a gas slug, adopted a depressed Dweenle as my engineer only to hear him complain that everyone hates him, slugged it out with spineless Spemin turned galactic bullies, and saved the known universe by traveling back in time.

I also have a notebook crammed with hastily scrawled coordinates and hints, snippets of conversations, and lines drawn everywhere linking scattered clues together as if I were living out the wall that Robert Downey Jr.'s Sherlock Holmes had assembled from his obsessive quest to unravel the mystery behind A Game of Shadows. He and I were on a mission to save our respective worlds.

Only in mine, there were lasers, space ships, and aliens.

Where did it come from

Binary Systems, the devs behind the first Starflight, created the sequel and EA published it in 1989 for MS-DOS PCs. It was later ported in '91 for the Amiga and the Macintosh. After those halcyon days, it and its predecessor wandered in bargain bins and eventually found themselves lost among abandonware sites online for years afterward.

I'm not sure if it ever appeared as part of any collection since then as physical copies became more difficult to hunt down. Then more recently, to the surprise of many, it re-appeared in an official capacity as a bundle on Good Old Games on November 24, 2011.

“That's no moon. That's…really huge.”

Starflight 2 built on top of what made the first game fun. The back box cover boasts over 500 planets and thirty alien races, six of which also have ships of their own and not all of whom were happy to see you. A twisting storyline, plenty of space to explore, and diplomacy wrapped everything together. All of this originally fit on two single-sided 5.25 floppies for the IBM PC which makes it smaller than most Xbox Live patches.

Many of the mechanics behind Starflight 2 hold up even today. They have to, especially if you're a stickler for graphics. Starflight 2 was came out first to the IBM PC, but it was then ported to both the Macintosh and the Amiga in '91. The Amiga version, in particular, sported far better visuals over its VGA counterpart though the back of the box featured screenshots from the IBM PC version. The Good Old Games version is the one for the IBM PC.

Slingshot Around the Sun

Starflight 2 takes place some time after the first game though it isn't necessary to get the gist of what is going on. The Spemin, the antennae'd blobs who talk big but were cowards at heart, have now become a Scary Galactic Threat ™.

Somehow, they have acquired powerful weapons and shields that work in nebulae and have threatened your home of Arth with ultimate destruction at the hands of THE SPEMIN DEATH FLEET (their caps). Whether or not such a fleet exists isn't the point. How they have become so powerful, and have access to an unlimited amount of fuel, is. Eventually they'll find the courage to follow through with their threat so before that happens, you need to find the source of their technology, seize it, and put an end to their plans.

Despite the threat of a SPEMIN DEATH FLEET, there is no time limit. The game cuts you loose inside a space sandbox from start to finish leaving it up to you to follow whatever leads you find interesting. If you wanted to shoot at everything, nothing prevented you from setting your mission to kill – just don't expect to finish the game or survive without help for very long.

If you just wanted to fly out there and check out things for yourself, you were free to do that, too. Only there was this little thing called “Shyneum” which acts as your fuel. Running out of it didn't necessarily end your mission, especially since you could call for help, but don't expect to get off without a fine for neglecting to top off.

The first order of business is to get a crew together. Unlike many other CRPGs, this one allows you to generate a crew from a number of alien species and pay for their education. It's tempting to max everyone out with the cash you have on hand, though best avoided if you still want to be able to put gas in the tank and trade for anything more than seeds.

Yet, it's also key to at least get a few trained up to avoid embarrassing mistakes. A skilled Navigator can give you the coordinates of space you're in right after jumping through a wormhole to avoid getting lost. A trained Communications Officer will be able to display more than gibberish when talking to your neighbors.

And it's the aliens that make the art of diplomacy, and your posture, a lot more important than your aim be it Friendly, Hostile, or Aggressive. Being Hostile with everyone was the surest way to becoming space dust, though with the G'nunk, it's expected before they decide to kill you as a favor for being weak. They didn't like waiting around, either, and would occasionally wonder if you were going to say anything or simply decide to leave if you just sat there.

Trade is also at the heart of the game. Starting out with only a small amount of cash in an unknown sector of space, finding out who wants what without running out of fuel led to a few false starts until I finally found a route that worked. Bartering for a better price on everything was also added an additional layer of the unknown. Pushing a prospective customer only so far walked the fine line between getting a huge bonus for your goods or pissing them off entirely and having them refuse to buy it. Period.

Talking with the different alien races floating about in space, grilling them for info, and bringing them special treats, had also dropped pages of notes into my lap. Not only did the aliens appear very alien, they were fleshed out with deep layers of text to give them character. Flying to the ends of space just to hunt down more to talk to kept the explorer in me busy for hours on end.

Combat was sometimes unavoidable. Arming shields and fighting with missiles while circling around enemies was basically the only tactic I used, though survival was a far different matter early on when my ship was about as intimidating as a Constellation-class pinata. But, after enough trades, I could finally trade a few shots and take down even the Spemin.

Safeties Off

Being an older game, there weren't many creature comforts. Saves, at least in the Good Old Games version running under DOSBox, are handled in a simple menu that didn't ask you if “you were sure” every step of the way. No auto saves here. Only so much could fit on those floppies making this a very hands on experience.

Combat was ugly, but functional. That green stuff is actually a big nebula. The bright

green dots are aliens, red are their missiles, the white dots are from my weapons,

and that tiny grey Y shaped thing is me trying not to die.

Keeping track of clues was made a little easier as you could replay dialogue read from each race, though due to limitations at the time, you had to scroll through all of the entries to find the one you wanted. It was often easier to just write down hints and reference it the old fashioned way. At the same time, this also made solving the open ended quest highly dependent on how good a note taker I was (and thankfully not because of my handwriting).

Trading made exploration that much more interesting as I sought out distant worlds on the included starmap for races that might be willing to give up a few precious items – along with some Shyneum for my ship – that someone else might desperately need. Sometimes this even made certain artifacts available to me after I proved myself a 'decent' trader.

Each dot was a star system and the lines indicated wormhole routes

through the ether. MUST….EXPLORE…IT…ALL…

But the same trick that could stuff hundreds of worlds on these disks had also made it tedious business from time to time. A procedural method was used to generate each world with a few hard coded locations pertaining to the story. Using this was the equivalent of having in-game cinematics – it saved a ton on space without compromising the appeal of the game. In this case, having a huge variety of worlds to mine for ore and explore.

The problem was that the trading posts were sometimes as random as the landscape, on occasion changing locations after leaving a planet and returning later. Since you couldn't scan for trading posts from orbit, you had to search them out at random leading to a lot of wandering around that was boring as hell.

Finding a planet with a potentially new trading partner? Great! Having to wander

around on the surface because you can't pick out interesting things like a trading

post from orbit? Shoot me out the nearest airlock!

What usually awaited you on a random planet? A whole lot of nothing.

There wasn't much to these planets when it comes down to it. Sure, there were minerals you could mine for ship repairs or for sale to other aliens IF they were buying. Though the idea that there might be something special outside of the story lurking on one off of the beaten path was always in the back of my mind.

Sometimes there was, but only if another race let you know that there was something worth finding on a particular world. When rumors and hearsay hinted at these special places, the potential for the game re-asserted its Kirk-like visage. Unless, of course, it was more fun to stun native life and cram them into your ship for sale elsewhere.

Set Course for Home

Discovering my first successful trade route, giving my ship some needed teeth, and meeting all sorts of strange beings while digging into the past all appealed to my inner adventurer drawing parallels between the Starflight series and other titles decades later such as Egosoft's X series and BioWare's Mass Effect. Even the note taking gave the experience a tactile aspect – and made it easier to appreciate the development of in-game journals.

The emptiness of most of the planets in the game was a minus if only in hindsight. Until I reached the end, simply knowing that there could be so much more out there awaiting discovery was as much an impetus to play as the storyline.

A new system! What mysteries await us here? Also, my Dweenle

crewman has some concerns. Again.

The impact of having a well trained crew on my side affecting things such as simply being able to talk to another race, finding my bearings in space, or whether or not a planet would crush me with its gravity if I decided to touch down for a visit, could never be underestimated and added a degree of uncertainty at the start. Once I figured out what I needed, my survivability was as much a reward as it was in landing that first sale.

Other pieces are also reminders of a very different time. The manual alone starts off with pages of in-universe fiction along with some hints as to what to do first as there was no in-game tutorial. The pixelized surfaces of its worlds and the icons running about tested the imagination aided by drawings of eight legged rhinos and bronze harpooners on its last few pages. A starmap was required to get through the game as well as its copy protection. Failure would mean that several game days later, an interstellar cop would show up in the game to end it for you.

That's a very large thing out there. And we couldn't take it with us.

A game called Protostar came out from Tsunami Media in '93 and was intended to be Starflight III, though the devs couldn't get the name "Starflight" from EA. Unfortunately, it didn't do very well especially when the market had changed since '89 with the likes of LucasArts' X-Wing, Accolade's Star Control II, and Origin's Wing Commander.

CGW's Paul Schuytema, in writing his review, was impressed by Protostar's visuals and the atmosphere though less so by the actual gameplay which seemed to lack any real direction. Combat fared even worse as he cited taking over "20 minutes (real time!)" to finish off one enemy using "the most powerful weapon". In the end, he suggested that vets from Starflight will be less impressed than those who are "anxious to see what the genre has to offer – and who hasn't played this sort of game before".

But that hasn't stopped fans from attempting to keep alive the spirit of Starflight, or others from mimicking its success with games such as Origin's Privateer borrowing a few notes from it and other peers such as Elite. There's also a group dedicated to building an actual Starflight sequel called Starflight III: Mysteries of the Universe, though it doesn't look like there has been much progress yet.

Other die-hards have even gone so far as to build their own "Starflight" game such as the impressive indie project "Starflight – The Lost Colony" which was developed over a number of years with the blessing of Rod McConnell, one of the original designers of Starflight. You can download it from the official site which also goes into some detail as to how it was created.

The Lost Colony is fully featured and takes place inside the universe of the first Starflight,

just in a different part of it. All the mechanics are there with a few modern tweaks

and the unique art style gives it plenty of personality. Try it out!

Not every game ages gracefully. Audiences can often outgrow that which they had started with and Starflight 2 is no exception.

But the themes remain as timeless as its legacy easily attests to. There's no question that as “hardcore” as Starflight 2 is in certain respects because of what the gameplay lacks, the same gameplay drops as much responsibility into the player's hands as the real captain of this particular enterprise.

And that's one lesson that should never be outgrown.