This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

"Fuck secondhand buyers." "Whatever. I don't mind." These voices in favor of online passes are too loud and too quiet, respectively, and they're the sentiments I usually see on this side of the debate. Some of the nay party’s arguments are flawed, too, so skip the next paragraph if you know what I’m talking about, then take in my case for the ayes.

For those who don’t know, online passes allow access to the online part of a game. This is typically its multiplayer, although it may constitute later DLC. Publishers slip cards with a single-use code in with games, and sell them as downloads (usually for about $10). They help get some money out of people who buy games secondhand, either through that fee, or by persuading them to buy an unused copy. (Misleading applications of the "online pass" label to locked, offline features (see Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning) are not what I'm talking about here.)

Not every secondhand sale constitutes revenue lost to the developer, but running a multiplayer service for paying customers costs as much as it does for everyone else — developers actually do lose money this way. Bungie, for example, holds detailed Halo statistics on racks of servers, they regularly change game modes to ensure variety, and they keep cheaters from ruining the fun through vigilant policing. These servers and staff cost money. When developers add to Xbox Live or PlayStation Network services, they have a right to demand compensation. And even if a studio would survive anyway, it’s not fair on those who support it financially to subsidise those who put a drain on it — at best it's unfair, at worst it increases game prices for those who support developers.

The main argument against online passes is that they detract from the experience for gamers. It’s short-sighted just to say “fuck the used market — they’re not our customers” because companies’ reputations hinge on how much enjoyment they give gamers, paying or not. But how much do passes ruin things? For $10, a used game is as good as new. And entering a code is a tiny, one-time inconvenience for everyone else.

If passes were unavailable to purchase separately, or extortionately priced, that argument would be valid. But anyone who prefers secondhand can still save money and fully enjoy their games.

For games with small audiences or poor multiplayer features, online passes would spoil everyone’s time by reducing the population of players. For example, The Darkness’ lack of blockbuster status and fun deathmatches led to hardly anyone being online. I was glad to have found anybody at all to hunt achievements with. I mean play with. Starbreeze’s next game (Syndicate) won’t have a pass, probably for at least one of these reasons.

Might not be fun or popular, won't require a pass.

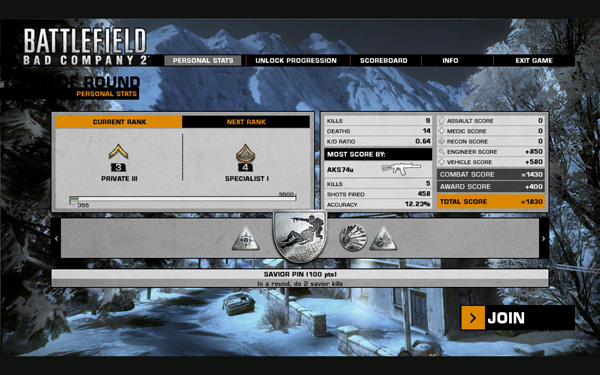

Used-game buyers often argue that the money they save on pre-owned games can be put towards future purchases of unused games and downloadable content, allowing them to take small risks on games they might have missed otherwise, and reward the developer later. This only helps those who intend to make sequels or similar games, or plan to release premium content after the game’s launch. Dice, for instance, could be happy paying to support multiplayer for someone who bought a used copy of Battlefield: Bad Company, if that person liked it enough to pre-order Bad Company 2. A used copy of the same developer’s Mirror’s Edge, on the other hand, won’t drive a sale for a sequel that isn’t coming. And they can’t rely on it to drive Battlefield sales — one can’t expect to enjoy an online shooter, just because it’s from the same people who made a narrative-heavy platformer.

That costs money

Let's entertain the notion that GameStop deserve to sell a game more than once. They still can. Let the price of a sealed game equal X, and the price of its used counterpart equal Y. Let A be the money given to whoever trades in the game, and B be any further discount they feel like adding.

X – $10 – A – B = Y

So long as Y stays above the cost of shelf space, they can continue to profit from others' creative efforts while offering nothing in return.

Decrying every single defensive move against used games hurts the legitimacy of complaints against far more harmful practices. Batman: Arkham City’s Catwoman DLC and Prince of Persia (2008)’s epilogue (downloadable for those games’ first owners) constituted significant components of concise stories, but were unavailable to the minority with unconnected consoles; PC gamers with too many machines, or who reinstalled it too many times, had to beg EA’s customer support to play Spore; and several of Ubisoft’s games won’t even launch without a connection to their DRM servers.

Having to type in a code, or download a small file for a reasonable fee, to play online is nowhere near that level of inconvenience or injustice.

It’s all very well to want carrots instead of sticks, but Microsoft, Nintendo, and Sony control online distribution to consoles, and developers can’t compete at retail with alternatives that will always be just a little cheaper with barely any degradation over time (cars fall apart — used games work as well as shiny, new discs). It’s easy to not see the ethical difference between paying someone for their own work and paying someone else, when both are legal and highly visible. And giving an in-game carrot exclusively to customers takes it away from the secondhand market and unfairly punishes everyone without a broadband-connected console.

Developers and publishers must minimise the inconvenience of used-game countermeasures, or accept a loss. Online passes achieve that minimisation, and developers shouldn’t be expected to support online play for people who aren’t their customers. Those without broadband connections can’t get online so won’t miss anything, and used-game buyers can fully experience their games without being extorted. Gamers can be happy they aren’t subsidising somebody else’s online play, and can demand support for online games whether they buy used or not. Everybody wins.