This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Ok, before I dig myself too far into a hole to ever come back, let me say this:

|

Genius incarnate. |

I think both Kickstarter and Double Fine, as companies, are awesome. Between Tim Schafer's artistic vision on games like Psychonauts, and Kickstarter's ability to help launch numerous start-ups and entrepreneurs, the two, individually do what they do well.

Are we understood? I hope so, because chances are, you're not going to like what I have to say next.

I have a really hard time stomaching the fact that Double Fine, a company that so many think of as 'independent' has, in reality, had a slew of success since Tim Schafer left LucasArts all those years ago, but can then pitch a point-and-click game potentially worth $1.6M at the time this article was written.

Even more odd, I find, is what it says about the industry and its fans, on the whole.

Double Fine, founded in July of 2000 by ex-LucasArts employees Tim Schafer, David Dixon and Jonathan Menzies, is a company that has come to be known for its quirky, typically non-conventional and often 'indie'-styled games. This eclectic mix has brought about the likes of Psychonauts, Stacking and Brütal Legend–all of which, at least after significant time on the market, have grown siginificant fanbases–and while all published by external companies (Majesco, THQ and EA, respectively) each likely brought the company a decent profit at this point.

It is these lauded games that allow companies like Double Fine to turn out games like Sesame Street: Once Upon a Monster for the Kinect, which, while creative and largely engaging for families with young children (like Schafer's own family), end up costing more than they'll ever make.

Less often will you find true 'indie' studios like Supergiant Games (Bastion), Playdead (Limbo) or Zeboyd Games (Cthulu Saves the World) making games they can afford to take a hit on, despite the success of their initial releases.

Why is this, you ask? Well, for one, how many of you could have named the developers of any of those titles, and beyond that, how many more of you can name the lead developer at any of those companies? While familiar enough to answer the first question, without the aid of Google I doubt even I could answer the second.

Having your company reach such a level of success that it allows your lead developer to become an industry figurehead like Schafer–think Epic's Cliffy B or Lionhead's Peter Molyneux as well–is just one of many signs that you may have transcended that hip "indie" moniker.

So, along with dumping the "indie" cred, Double Fine ought to give up on an idea like crowd-sourcing to pay for their next title. If not because they can afford to pay for in-house development and assume the risk involved, than because it's preying on the fans, who would likely buy your game anyway, and their heartstrings with a "this can be a game you develop" approach.

So, that's gripe number one. Double Fine, if you can't afford to develop and publish a point-and-click adventure in 2012 on your own, after 12 years of what we'll call "moderate success" (a generous short-sell), then you are doing something wrong. Despite how much we love you, and believe me, we do. Double Fine's Kickstarter succes is evidence enough, but coming to the fans for the money makes me lose respect for you.

Also, congratulations on your insane success, but if you only expected needing $400,000 to make this work, don't you think you could come up with some better use for the remaining $1.2 million you've made? Does the name Child's Play come to mind?

The second issue here doesn't fall as much into Double Fine's lap as it does that of the industry and its fanbase.

Listen, I have an N64 and miss my Sega Genesis and NES desperately. Every so often I get this nagging need to go back and play GoldenEye 007, Sub-Terrania or Super Mario Bros. 3, so I get it. Nostalgia is a huge part of our industry and always will be.

But at some point over the last year, we, as fans, managed to give the industry the wrong impression.

If you failed to notice, a large number of 2011 game releases were HD remakes and ports of older games. From GoldenEye 007: Reloaded to Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary, Ico and Shadow of the Colossus HD to the announcement of the Jak and Daxter Collection–just to name a few notable examples–it feels like the video game industry has entered a period of stagnation similar to the movie industry. The difference is that here, we're encouraging it.

Nostalgic experiences are initially fun, exciting and engaging, but the games quickly feel dated, clunky and not nearly as fun as I remember them. They then sit on a shelf, or on a hard drive and collect dust, never to really be played again.

So, looking to today, what has Double Fine offered us, and what have so many of us (45,139 of us to be exact) shelled out anywhere from $15 to $10,000 for?

A point-and-click adventure. A genre that debuted in the late 1970s with Sierra Entertainment and peaked somewhere in the early-to-mid 1990s.

A point-and-click adventure. A genre that debuted in the late 1970s with Sierra Entertainment and peaked somewhere in the early-to-mid 1990s.

Now, don't get me wrong. If anyone can handle the development of a strong point-and-click it'd be the team at Double Fine. From their time at LucasArts and the development of the Monkey Island series (which saw an HD do-over itself just last year) and Day of the Tentacle, the team clearly has a knack for the genre. This, however, does not mean that now is the time or place for a new one.

Don't believe me? Just think about how your average point-and-click game has degenerated into Facebook social games and hidden-object flash games.

I don't have to tell you these games suck. You know it, and I know it. But does that mean that Double Fine Adventure is going to be the one that kickstarts the revival of the genre (pun intended)? I doubt it.

Just think about how often we are calling for more original, captivating next-gen titles. Or, even more telling, the fact that while the current generation of consoles could easily last their expected 10-year life cycle, we've already started clamoring for the next-generation. We are a fickle bunch, we gamers. We want the best and the newest, and we want it now.

With that in mind, I have to ask: While a $15 "donation" earns you a copy of the title on release (which does sit in line with an average XBLA or PSN release), how many of you donated simply because it's Double Fine? How many more of you donated because those out there with influence and the money to actually spare (like Markus "Notch" Persson and Felicia Day) did?

Thinking back, do you wish you hadn't?

I'm not saying any of you should feel bad for putting your money on the project. The success of our industry relies on us supporting one another, being willing to put a dollar or two forward to help those we love produce the things we enjoy most–video games.

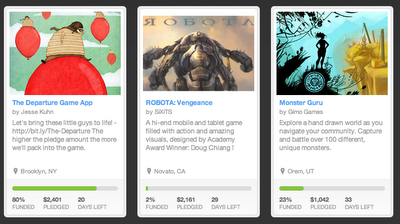

But as we all willingly shell out our hard earned dollars to support a company perfectly capable of developing a single point-and-click on its own, why do smaller game companies with Kickstarter projects (see just a few of many below) have such a hard time meeting similar earning goals?

Before I wrap this up, there is one other valuable point worth considering here, and it isn't mine. Developer, famed loud-mouth and industry figurehead David Jaffe of Eat Sleep Play recently spoke at the 2012 D.I.C.E. Summit.

According to coverage of the speech from Games Industry, a theme of Jaffe's speech spoke directly to game developers. Specifically, he called out their habit of over-selling their ideas early on, coming up with empty promises and games nothing like the unique original pitch. As he so eloquently put it, "You guys need to get a bullshit filter and you need to get that before you waste any more money…."

He continued on, addressing the companies that put up the publishing funds, by saying:

It's real easy to bamboozle you. It's really easy to sit in a pitch and talk about "I want the realism and grittiness of Breaking Bad and Sons of Anarchy and I want to put it on a space ship and make you feel like Tarantino and speak to the human condition." And you walk out of the meeting and you give them the green light because you can see that in your head.

But you can't see the game in your head, you can see the trailer to a movie that doesn't actually exist…You better start learning gameplay language…[then] you can actually sit with developer and say "it's cool that you want to do that but tell me how." If you come in with an awareness of that…that's great. You don't want to have a developer romance you with the promise of something more than it will ever be and it ends up not being that…

A lot of these people will say "I have something to say, I have a story to tell." If you've really got something inside of you that's so powerful, like a story you've got to share or a philosophy about mans place in the universe, why in the fuck would you choose the medium that has historically, continually been the worst medium to express philosophy, story and narrative?

Why wouldn't you write a book, why wouldn't you make a movie? It's like being one of the world's best chefs and working in the world's best restaurants, [but then] you ply your trade in McDonald's.

The sad part here is that he a valid point. What may be ever more sad is that if you look at the Kickstarter pitch language, 45,136 people have been "romanced" by pitch language for a game that doesn't exist yet–just like Jaffe says, and why? Because we aren't publishing executives, and whether maliciously intended or not, Double Fine knows that.

Here is just a smattering of some of that language:

This year, you'll be given a front-row seat as they revisit Tim's design roots and create a brand-new, downloadable "Point-and-Click" graphic adventure game for the modern age.

I'm sorry, but what does that even mean? What is a point-and-click adventure for the modern age? What emotional attachment have they suddenly created in all of us to get back to Tim Schafer's design roots?

[Kickstarter] democratize[s] the [development] process by allowing consumers to support the games they want to see developed and give the developers the freedom to experiment, take risks, and design without anyone else compromising their vision. It's the kind of creative luxury that most major, established studios simply can't afford. At least, not until now.

|

I can haz input? |

How much involvement can the consumer really have in the development of a game? While votes can be held, and opinions can be taken into consideration, without actually being involved in the day-to-day, the answer is "not much." Also, if the return for our fronting the money is allowing the game we want to see developed reach fruition, what risk is the company really assuming? Or, even more importantly, if nobody is compromising their vision, what effect will our input actually have on the end product?

First and foremost, Double Fine gets to make the game they want to make, promote it in whatever manner they deem appropriate, and release the finished product on their own terms.

Well, there's one answer, in a way.

Secondly, since they’re only accountable to themselves, there’s an unprecedented opportunity to show the public what game development of this caliber looks like from the inside….

Only accountable to themselves? Again, who is paying for this project?

And to sum up our Jaffe-infused Double Fine Adventure:

Not the sanitized commercials-posing-as-interviews that marketing teams only value for their ability to boost sales, but an honest, in-depth insight into a modern art form that will both entertain and educate gamers and non-gamers alike.

What are they really even saying here? There is no way to prove the sincerity, or lack thereof, in any other company's post-production reflection videos or developer diaries. This is blatant sophistry and nothing more than exactly what Jaffe was talking about, appealing to you with emotionally heavy phrases that largely distract from the end product–a game that would be better as a documentary, if Schafer's goals are what I understand them to be.

So where does this leave us exactly?

Odds are, my arguments will be seen as petty. Many of you will comment saying, "Double Fine is awesome!" or, "You're just jealous that you can't make that kind of money." I don't disagree with either of those statements. I do think Double Fine is a great developer, and I am entirely jealous that my own ideas wouldn't earn $1.6M in 48 hours.

That, however, does not change what Double Fine's success shows about the industry.

As gamers take to arms about potentially losing the used game market, complaining about the high price of new games and the beautifully devious thievery that is Online Game Passes, what message are we sending when we collectively put out millions of dollars for a big company to develop a digital title entirely on our dime? Without risking anything themselves?

If you don't think companies like EA, THQ, Ubisoft and Activision are watching this, stroking their beards made of money and thinking, "Well, if we can get gamers to front the cash for a game, and then find a way to make them buy the game, too–it's just so crazy that it might work!" then you're being naive.

Plus, how can we possibly rant about a stagnating lack of creativity when we show just how badly we want to play games from decidedly outdated genres?

In the end, it is moments of seemingly great success like this where we all ought to take a step back, use that 20/20 hindsight we're all so lucky to have, and start making the changes that matter. Then, and only then, will we kickstart a movement worth supporting–one with the potential to bring about the change that Double Fine has proven we so desperately need.

Justin Brenis (@TheJustin_B) is Editor-In-Chief at Pixel Perfect. You can find the site online at www.pixelperfectmag.com or on Twitter @ThePixelPerfect.