This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

It’s funny how I can enjoy a game like Braid so much yet still have so many fundamental disagreements with its creator’s view of game design.

Jonathan Blow made a number of thought-provoking points during his hour-long lecture, Conflicts in Game Design. Though I would love to dissect and discuss every little idea he brings up, one argument in particular really stuck with me.

In regards to straight-forward narratives in gaming, Blow argues that story and challenge are at odds. While the narrative wants to progress, the difficulty of video games push back. To him, this relationship is so unsound that it inherently prevents the medium from expressing good stories.

I respect the developer’s opinion, but I absolutely do not agree with it.

A game’s difficulty and the challenges it presents its audience doesn’t impede story; it is story.

In a simplified context of traditional narrative, a successful story is built on a risk/reward system. The protagonist wants something to happen, and with each decision and step they take, they either get closer to realizing that outcome, or the game pushes them further back.

An outside force or event usually starts the process, but the character in question is the one that ends it. Throughout the story, they try to restore the balance in their life by making risky decisions against antagonizing forces; they believe these gambits will turn the tide in their favor. Obviously, the protagonist takes small risks first, but their decisions hold huge implications for the character and ultimately defines who they are.

In this sense, video games are perfect for expressing an involving story. The player isn’t supposed to empathize with the protagonist like other mediums; they should be the main character as if everything is happening directly to them. It’s not good enough to simply tell the player that the main character takes huge risks. In a video game, the player needs to undertake the task themselves and experience the risks firsthand.

My interpretation comes from worshipping the Super Nintendo (SNES) as a child, watching Quentin Tarantino movies behind my parents’ backs, and reading great books like Story by Robert McKee and Stephen King’s On Writing with gaming in mind. I’m also well aware that a great story can come in many different ways, and interpretations can be a lot less formal than mine.

But this framework helps me understand why a seemingly well-designed game like 2008’s Prince of Persia failed to engage me. Having the Prince’s partner, Elika, save him from certain doom throughout the game eliminates the need for frustrating game over screens and endless load times. But at the same time, it rids the world of consequences, so I’m free to take as many risks as I want. Nothing in the world intimidates the Prince, making the gameplay void of any emotion. Getting through a section feels like work, and though the story is lovely, it fails in the guise of a video game.

Mind you, by difficulty, I don’t mean enemies that spam cheap attacks or being a target for every grenade in Japan. A true video-game challenge comes from familiarizing yourself with a gameplay system and then having your prowess tested just enough through situations exclusive to that structure. A game doesn’t need to kill the player hundreds of times, but the developer can’t be afraid to push their fans past their limits.

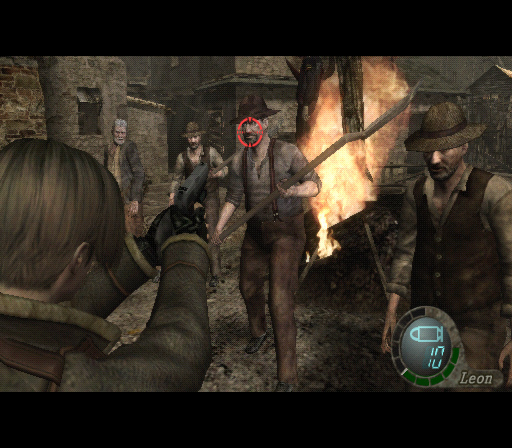

In Resident Evil 4 I only died a few times during my initial playthrough, but every moment of that game was wrought with tension because of the excellent pacing. Through gameplay, the developer illustrates the basics of dispatching an enemy, using the environment to your advantage, and weapon proficiency.

The player soon engages in a battle of survival in a small village packed with hostiles. You burn through your limited inventory quick, and you eventually face down a handful of villagers with nary a prayer left. You fought an exciting, adrenaline-pumping battle, but it’s obvious you have failed as the villagers inch ever closer to you.

But then it ends.

The Ganados are drawn away from the battle, leaving you with shot nerves and soiled trousers. Right from the outset, the player learns to respect the game’s challenges and fear death, making their journey and accomplishments that much more rewarding. The game is so memorable because it consistently pushes the player to the brink but allows them to use their wit and determination to succeed without dying multiple times.

RE4 is a testament to how the steady progression of difficulty can help elevate a gaming experience to new, visceral levels. The story is definitely on the goofy side, but the fear it invokes in the player is as potent as any horror film or book.

Blow has a few good arguments, but in the grand scheme of things, I don’t believe this is one of them. Difficulty and narrative go hand in hand.