This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

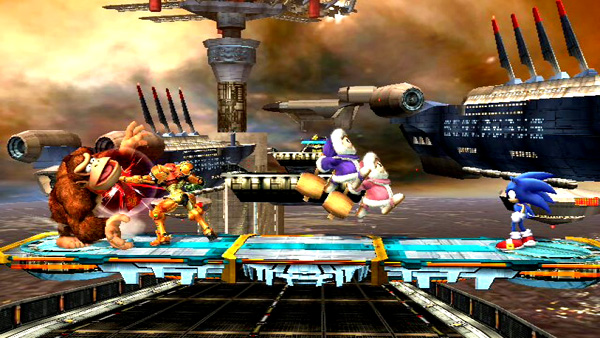

Rarely has a game come along so brazenly disdainful of gamers, and gaming as a whole, as Super Smash Bros. Brawl. Designed to appeal to creator Masahiro Sakurai's warped vision of what a competitive multiplayer game should be like, Brawl has surprisingly — alarmingly — won the hearts of gamers and critics alike.

"Man, what a cool looking game! I sure would like to get better at it –"

Billy, moments before Nintendo's secret police took him away.

The Super Smash Bros. series has always walked the line between fighting and party genres, with a dedicated competitive scene and casual fans embracing the novel concept of iconic Nintendo characters locked in 2D combat. A fighting game series, despite arguments to the contrary and admitted accessibility to groups of friends looking merely for a good time, Smash Bros.'s take on 2D fighting is rather different from the approach offered by Street Fighter and refined by many developers over countless iterations. The series mixes platforming, distinct battlefields, and a unique take on the "ring out" win condition.

As competitive fighters, Super Smash Bros. and its sequel, Super Smash Bros. Melee, were accidentally sound. Very clearly not designed for high level play, its loyal fans drafted rulesets to turn Smash's inherent chaos into a deep, strategic game. The quality of that community, including its rulesets and the individual mannerisms of its members, is beyond the scope of this article, but the fact remains: the Smash games were serendipitous structured fighters with community backing and a real hardcore scene.

Apparently Masahiro Sakurai, creator of Kirby and father of the Smash Bros. franchise, disliked this idea, intending Smash Bros. to be a non-serious party game series. He sought out to put a stop to this.

Before we continue, a few thoughts:

Some people play video games to kill time or for personal betterment, some primarily with friends or by their lonesomes. Games are many different things to many different people. And any given game designer no doubts aims for a certain audience. Reverge Labs' excellent Skullgirls aims at fighting game enthusiasts and tourney players while leaving the door open for newbies interested in learning the genre. Braid aims to tell an interesting story through on-screen text, haunting music, and player interaction.

It was a nuke. Or Andromeda. Fine, I don't know what it was, but Fickle Companion's star can go to hell.

But Mike Z. wouldn't dream of purposely making special moves in Skullgirls arbitrarily difficult to keep out anyone not willing to take it seriously; some people bought Skullgirls for its art and music, and they've every right to enjoy the game in a less than serious way. Jonathan Blow may not be jumping at the bit to make competitive multiplayer games, but he won't instigate measures stop speedrunners from competing to try and finish Braid as quickly as possible.

It's seriously head scratching why Sakurai would purposely aim at competitive players. Or anyone. Seriously, he took aim at a subset of gamers to specifically smite. It's inconceivable.

But smite he did in Super Smash Bros. Brawl, the latest entry in the series.

And in doing so, he introduced the single most anti-gaming mechanic ever to grace a first party Nintendo title, a mechanic targeting the competitive player… but bad for everyone, no matter how casual or hardcore.

It's called "tripping."

Ike tripped into this cage. He'll get no sympathy from Sakurai.

Here's how it works: whenever you input a dash (faster movement on the ground), your character has a chance to stumble over their own feet, leaving them wholly vulnerable for a moment.

There's no way to avoid this, no way to turn it off, no way to play skillfully enough to avoid it without using a character who doesn't need to dash (most characters need to). Its absence would have negatively affected squat, and its presence couldn't be defended if humanity's continued existence itself was on the line.

This mechanic, this unneeded, unwarranted design "feature," flies in the face of any sort of reason. It serves to benefit no one. Intermediate and advanced players must now find ways to avoid dashing lest they risk vulnerability caused neither by their own misstep or their opponents' cunning. But tripping doesn't just hurt them: casual gamers are left to wonder why this cornerstone ability — dashing –arbitrarily punishes them only sometimes, putting a dent in any desire they may have to improve.

There can be no betterment; there can barely be a base game with tripping in place. In this real time fighting game demanding fast reflexes and both physical and mental dexterity, basic movement — repeating for emphasis: basic movement — is subject to a success/failure dice roll.

No well designed game on this planet, regardless of genre, features such a contemptuous, out of nowhere punishment for engaging in basic movement.

That shadow will trip Link every time Link loses a dice roll. A+ Gaming!

I'm not a fan of the Street Fighter 3 series' parrying mechanic, an all-purpose and free defensive maneuver that contradicts what every Street Fighter without the number 3 in its title has been about: thoughtful positioning and the mind games inherent in that positioning. But parrying requires a conscience decision; even parrying can be baited and punished by the perceptive player. Tripping cannot be predicted, cannot be planned around. It just… happens. Just because.

In Super Mario Bros. 3, World 6 features icy surfaces that muck up Mario and Luigi's footing; this doesn't happen at random, and can be planned around. In Castlevania, Simon has a brief delay between when you tap B and when he actually whips; this is part of the game's design, with levels and enemy layouts planned around it. Jamestown features a selectable ship that randomly mimics one of the 7 other ships; any player who doesn't desire this can merely directly pick the ship they want. Even card games — everything from poker to Magic: The Gathering to Yomi — have random elements that can be planned around and turned to a player's favor. None of these games just up and put your player character at the mercy of an enemy because your d20 came up 1.

Speaking of dice, tabletop role playing definitely has an element of chance. Where it differs from a real time action title like Super Smash Bros. Brawl is that players seek something very different here; objective betterment isn't really the point of tabletop roleplaying as much as experiencing a (hopefully) compelling narrative through the perspective of your (hopefully) interesting character you're (hopefully) into roleplaying as. That, and a good game master can smooth things over to best ensure a fun time is had by all, even the perpetual bad roller.

Super Smash Bros. Brawl's tripping mechanic comes from a designer's contempt for betterment through gaming, which in and of itself should disqualify anyone from making games in any capacity. But this contemptuous philosophy attacks players at all levels, not just the one demographic wrongfully, unnecessarily targeted in the first place.

By itself, tripping should have earned the ire of anyone who wasted money or time on the game, from consumers to reviewers. But it didn't. On the receiving end of massive accolades, Super Smash Bros. Brawl sold very well. It enjoyed much praise and little criticism, a fact often touted by its fervent defenders whenever the game's very real flaws, tripping included, are brought up.

This isn't even touching on the mountain of unlockable characters, ensuring I can't practice as Wolf until I somehow "prove I've earned it" to this sloppily put together collection of 0s and 1s in my Wii's disc drive. Or the inability to circumvent unlockables by porting a save file. Or the virtually non-existent combo system. Or the poorly-made stages, like WarioWare Inc. which throws invincibility power ups onto the field for anyone to grab regardless of who correctly played the stage's mini-game. Tripping is merely the largest rock in the misstep jar.

In fairness, Brawl did address some issues from its predecessor. Like it or not, L-cancelling is gone, and for the better; it's not sound design to require a button press every time a move comes out just to reduce its recovery, as with no cost, it's always the better option. Wave dashing arguably falls on the wrong side of unnecessarily difficult execution despite the advantages it imparted certain characters. And it's always good to see a Wii game that doesn't force a Wii Remote control scheme in favor of giving players the option, a foreign concept on the Wii for some bizarre reason.

Dedede always rollin' dem snake eyes.

But a handful of pros don't even begin to outweigh the overwhelming cons. Super Smash Bros. Brawl treats any who would play it with contempt. It sabotages an otherwise functional, customizable control scheme to push its creator's shallow ideals, damaging gameplay for all audiences, from the skillful competitor to the casual hobbyist. A medley of additional flaws ensures it can never be enjoyed at even a fraction of its potential.

For this contempt, for these deliberate and backwards design decisions, gamers and press rewarded Sakurai handsomely. And we, as gamers, are worse off for that.

Screenshots from GiantBomb's archive.

Carlos Alexandre is a self-described handsome fat man. He ponders his entertainment, and you can find said ponderings on both his website and the podcast he co-hosts.