This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

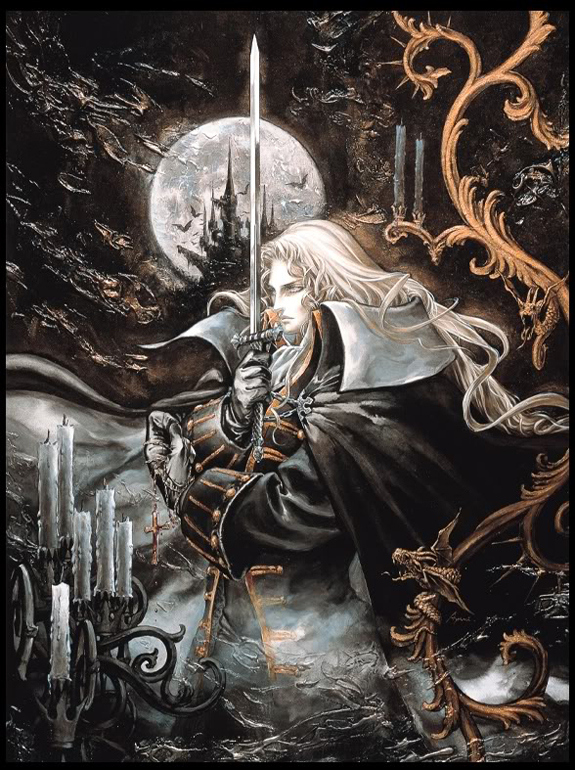

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night turned 15 a little while ago and I’d just recently finishedShadow Complex for the first time, so I thought it’d be nice to finally knock this one out. Even playing it from my inverted viewpoint of the series, I can say that this game definitely holds up. Even with a few big modern games in my face I still found myself wanting to play this game. It even feels timeless for the most part, even if it’s due to some technicalities.

My first Castlevania game was Circle of the Moon at the GBA’s launch in 2001 – in fact that was my first “Metroidvania” game, having never touched a Metroid game until Prime and Fusion came out a year later. Aria of Sorrow and Dawn of Sorrow however are probably some of my favorite Nintendo handheld games of recent years with their surprisingly refined game design. I never got affordable access to Symphony until the PlayStation version came out on PSN a while back, so I’m only just now seeing why the Sorrow games felt so refined. Even today Symphony feels like a shockingly deep game.

Circle of the Moon, and now Symphony being the earliest Castlevania game I’ve played, I have no concept of the transition from the older games to the Metroid-inspired entries. I can only imagine the revelation series fans felt in 1997 when they discovered they were playing as a half-vampire with traditional vampiric powers like transforming into a bat or fog, and then having to actively explore the castle like in Super Metroid three years earlier.

From my perspective, Symphony felt like a new addition to the GBA and DS games, even in terms of graphics, and a very good one at that. The current Castlevania formula has been called “dependably good” – a franchise that has fallen on a perfected formula, so much so that the original years-old blueprint still holds up.

I wanna say that the main reason Symphony holds up so well is because the “Metroidvania” subgenre really hasn’t advanced beyond it. The subsequent Castlevania and Metroid games on Nintendo handhelds merely manage to be as good in terms of tech, level design, and depth. Looking back, I would say that Dawn of Sorrow lives up to Symphony without necessarily surpassing it on an objective level (fans will always have their favorites). Even Shadow Complex merely evokes the formula with its own tweaks instead of providing its “next level”. Even the 3D Metroid Prime stands alone as its own sub franchise. It might be better though that these games stand out as so unique that they don’t become obsolete.

The one thing in Symphony that is however undoubtedly superior to its successors is its audio. Being a CD-ROM game, its arranged music and voice acting would unavoidably have an edge over the still-great audio of the handheld games. Even if the voice acting is pretty painful at times (very much of the era), I found myself downloading the soundtrack pretty soon after starting the game.

What did feel oldschool about Symphony though – in a pleasant way, was how it let me discover stuff. Yahtzee on Zero Punctuation – who in his review had also just recently playedSymphony seemed to complain that the game refused to spoon-feed itself to him, or be forward about much of anything, and that’s something I miss in games. In the case ofSymphony it made a technically small game feel big, with secrets that you had to uncover.

Firstly, the whole concept of the game is to explore and discover more rooms in the castle. The game just telling you where to go like everything does today would probably ruin that. The big example is the secret of the clock room – probably the central mystery of the game, not to mention the fact that you can seemingly beat the game, get an ending with credits, and assume that’s it while actually having missed half the game’s content.

Dawn of Sorrow pulled this too and I thought it was cool then, but I guess Symphony is where the idea came from. Having played Dawn is probably why I felt like Symphony’s first ending was the “crap” ending. What I didn’t see coming was the appearance of an upside-down version of the entire castle I’d just beaten, even after 15 years. It’s like “wait, I get THIS much more game to play?!” The “anti-castle” as I’ve called it, feels halfway between a lovingly designed new game plus and the actual second half of the story.

There’s also the way Symphony presents its gameplay mechanics. A big one for me was the library card. I’d collected around a dozen of them wondering what the hell they did, and finally said “holy crap” upon using one to find myself transported back to the merchant in the library. Any game today would just outright tell you “use the library card to visit the merchant”, but Symphony lets you wonder and discover on your own.

This kind of backfired a bit too though. I resisted GameFAQs while playing Symphony and I think that was the right decision – enriching each discovery I made on my own, but there were things I just wouldn’t have figured out without the random forum comment. I didn’t even know I could cast spells until the second-to-last boss. I completely missed the ability to survive water for most of the game, and might never have discovered a crucial pathway. Apparently there are people who’ve been playing this game for 15 years and never figured out that you could swim wile transformed into a wolf. There are still a handful of doors I haven’t figured out how to unlock yet.

I can see why fans would keep coming back to this game for 15 years. It is very much made for players to discover new things each time they play it, whether that be the secrets of its two castles or its tastefully refined gameplay. It also stands timeless as arguably the pinnacle of a design formula.