This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Though the topic is regularly beaten into the ground, the discussion whether video games are art depend on insider versus outsider relationships. People involved in the video game industry or those directly enamored by the narrative structure of video games, their stylistic choices, and their use of imagery vehemently defend the status of video games as art. In comparison, those familiar with more traditional mediums may discard the concept of video games as art.

This article is not about rehashing major, simple, used-for-Youtube arguments. This article is about thinking beyond that. This article gets into the ugly.

I’m not trying to convince you of anything other than the debate is more complex than a wikipedia entry have you think. The topic depends on semantics, works, and media portrayal, but also being lost in a lot of translation.

It’s a challenge of ontology of both art and video games, and it can get quite thorny. These are the reasons that are rarely mentioned, and even more rarely touch upon discussion in most video game media, because they’re hard questions to approach. They don’t have clear answers, but they’re crucial to evaluating the medium.

These are the complex reasons. These are the reasons you’d immediately say ‘this is stupid’, until you read a hundred books on Kazimir Malevich and think ‘wait a minute’. If there was a Professor in Video Game-ology, these are the types of arguments he’d write journals about. These are the arguments that you can confound and contest in a drunken stupor at a bar. This is the suck.

Video Games are Art because they bear Hineinlebenshaltung

Hineinlebenshaltung is roughly translated as ‘living-into-it orientation’. The intent of Hineinlebenshaltung is to look at a piece of work naturally having a meaning or a message. Along this line of argumentation, a video game is a piece of art because it has the potential to bear meaning to a message.

Games, similar to movies, books, and so forth, depend on symbols to accentuate the meaning of their works. Many horror games, for example, draw upon basic jungian and freudian archetypes and imagery to display primality. The use of Hineinlebenshaltung, in other words, defends video games as art on the grounds that they can enact symbols and meaning, giving gravity to their work.

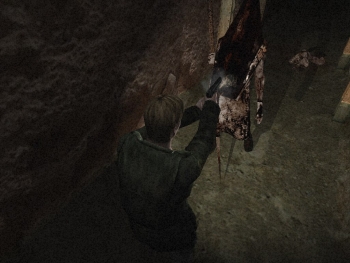

Silent Hill 2 is the most often cited example of work depending on meaning through exaggeration. James’s descent into the nether-town is plagued by monstrous beings which represent various aspects of his tortured psyche.

Video Games are Art because they facilitate intersubjectivity

This argument states that video games are art because its worth depends on the exchange of idea and communication between all involved actors. This argument draws from semiotics, working on the formula that a cohesive piece of work depends on three things: the creator of an image, the medium of the image, and the interpreter of the image.

Along this line of logic, works of art are art because they can be created with the intent of being art and are interpreted as art. Though it seems like a cop-out argument at first, intersubjectivity giving value to a piece of work drove a lot of cubist and surrealist work. Intersubjectivity is an immediate heightening of message of a piece of work beyond its physical components, which is why it’s important as a component to a piece of work.

Braid is a good example of a video game that bears value through intersubjectivity: because it frames itself in an artistic fashion, and it interpreted as being artistic, it is artistic.

Video Games are Art because they seek mimesis

This argument states that video games seek representation and imitation in the world through the lens of an artist. It takes an Aristotelian look at nature and attempts to mimic it in the way that suits a particular idea or ethos.

This doesn’t necessarily mean it depends on being realistic to be artistic. Mimesis in the context of art, at its base, argues for representation of both physical and nonphysical reality. Scenery and psychological torture are both equally viable subjects for mimesis. This line of logic dictates that art in video games are art as long as they provide an interpretation of reality according to intent and meaning. What this reality means, however, depends on the creator.

Nintendo’s Earthbound is an example of Art as mimesis: the story touches upon the subject of motherhood, and its plethora of feminine imagery mixed in with isolation and desolation paints a reality family cleavage.

Video Games are not Art because they lack intrinsic value

The argument against video games as art can depend on the lack of intrinsic value. Intrinsic value is the belief that something is valuable both universally, naturally, and in itself. An act can lead to eventual intrinsic value, insofar as the value does not lead to something else. ‘Happiness’, for example, is an intrinsic value because its an ends in itself.

The other value is instrumental value. Instrumental value is when something is valuable because it leads to an intrinsic or instrumental value. Money, for example, is instrumentally valuable because it leads to food, which leads to life. You can argue that video games are not art because they lack intrinsic value. Instead, video games lead to instrumental value because they create utility, which is an intrinsic value. The value of art is in its potential to be an entirely intrinsic piece. Because video games are arguably impossible to achieve intrinsic value, they can’t be art.

Any game created purely to titillate and affirm, such as hentai flash games, dating sims, etc., are considered examples of video games being completely instrumental. Call of Duty games, additionally, are examples of instrumental value due to their creation to fuel a constant lucrative industry.

Video Games are not Art because they lack pure linearity

This is a thorny, but potentially compelling argument. Video games are different from traditional means of art because they provide nonlinearity. Novels, movies, radio, etc., are considered mediums of art and art because they have strict linearity.

Linearity is important to this argument because it clings to an older conception of artistic value. A piece of work is defined only by its efficacy in determining its ultimate message: as such, it requires linearity as its whole. Nonlinearity, critics argue, potentially dilute the value of the message and meaning of a video game, and therefore cannot be valued as art.

Though proponents of this argument concede that there are fairly linear games, they all have a level of customization and flexibility considered unfathomable compared to movies, novels, and paintings.

The Mass Effect series, for example, is an example of the argument for strict linearity. Because of the nonlinear nature of the game in the face of its linear ending, it’s hard to call the game artistic. You could say the ending was artistic, or attempting to be artistic, but that doesn’t mean the game itself was artistic. Parts do not necessarily define the whole.

Video Games are not Art because they must depend on structural rationality

This is the most difficult, and yet most interesting argument I’ve come across. All games require a structure to succeed, or else it becomes a gibbering mess. The problem with that, however, is that other mediums of art can be a gibbering mess for the sake of being a gibbering mess and still be considered artistic.

Dadaism and extreme German Expressionism can be applied to most mediums, but they are significantly more limited in video games. Video games depend on ergonomic consistency to function: at the end of the day, no matter how pretentious Indie Title A is, it can’t escape from basic foundations of controls. Along these lines, because Art can be a self-aware deconstruction of reality to a higher purpose, video games are not art because they can’t break out of the mold of good game design. If they do, they fail to effectively provide their message.

Fable 3 is an excellent example of how video games have difficulty escaping from the shackles of control design. It attempts to break the mold by eschewing most of its menu system, but reception was mixed, sometimes dismal.

So, why is this important?

To be honest, the term ‘Art’ is ever-shifting, ever-changing, and isn’t terribly important. Its value is dependent on how strongly and maturely its proponents can take criticism. Video Games can only be considered art insofar as it innovates conceptions of reality, spirituality, and logos. But to do that, we need to approach the higher, more theoretical arguments that continue to plague us.

Sure, we have critics such as Roger Ebert arguing they’re not art, but he’s the tip of the iceberg. Video games can create work and narratives that are compelling, engaging, and enthralling: Dear Esther beats out Transformers’s narrative any day of the week. But pretty words, gloomy atmosphere, and words for the sake of words isn’t going to get the ‘video games are art’ field anywhere.

Ultimately, my position is ‘why bother?’. Video games can create art, or formulate pieces of art, yes. But are they art in themselves? Perhaps, perhaps not. Perhaps we need a re-conception of the term ‘art’ to suit this relatively new medium before we can expect curators making a living on old Ataris and Mario pots. Perhaps we need to break away from calling certain games art games and just call them all pieces of art. But until then, there is one truth I believe in: we’re on the defensive.