This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

I'm frustrated that the tradition of journalistic coverage on video games has now become a sort of joke told with Doritos in one hand and a cup of Mountain Dew in the other.

When I wanted to reply to community writer Nathaniel Dziomba's excellent article, "Games journalism never had any integrity" — particularly on his point that he had led in with, what I imagined as a short snippet went beyond what I expected it to. His article and those brought together within community manager Layton Shumway's collection of Bitmob's thoughts on games journalism made me wonder: How did things get the way they are? And is there anything we can do about it?

The incident in question reminded me of the heady days when the console gaming mags began covering the revival of the market led by Nintendo and Sega. In retrospect, a number of them presented themselves as glorified fanzines in opposition to the sometimes dry and analytical coverage reserved for PC games on the pages of magazines such as Computer Gaming World or Compute!.

I was part of the problem because, I'll admit it, my younger self loved the colorful splashes of full-page ads, two-page spreads talking up games (that I might not play because I couldn't afford them), or the light reading that didn't take itself too seriously. Magazines were as excited at the revival as the kids and young adults they catered to. It wasn't about "PC vs. consoles," only the old adage of writing for your audience.

The layouts and seemingly chaotic mash up of full-page screenshots scaled up as wallpaper alongside comic strips and mascots made me look forward to what Sega and Nintendo were coming out with next. They were attention grabbers. That's what they were there to do.

Those early days were filled with plenty of newsstand eye candy pushed along by exuberance born by the NES and the Master System arriving in the US. The cynicism hadn't tempered anything yet outside of a few readers' letters in PC magazines that began covering bits and pieces of the emerging market. Why was this stuff showing up next to my Macintosh conversions?

Publishers would take out two- or three- or even four-page ads for games almost on a monthly basis. Posters and fold outs would join the mix.

Yet at the same time, biting reviews would begin finding their way into many of the mags as they matured over time — sometimes for the same games that were being advertised in their own pages.

In reading up on older games and hashing through their contributions, it has been an eye opening experience to compare the style and topics of articles dedicated to the medium from as far back as 15, 20, or even 30 years ago in covering the same thing — in seeing the same kind of questions being asked and challenged from the arcades to the Commodore 64.

And I'm not talking retro gaming. I'm talking about the attitudes and business decisions that led to the boilerplate disclaimer letting readers know that Scorpia's columns in CGW were her own words or Softline's article in 1982 on how a game like Wizardry helped to pull a child back from the edge.

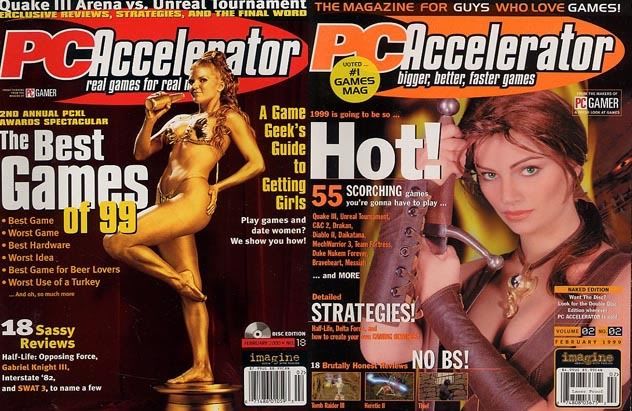

One magazine, PC Accelerator, rocked the boat with witty writing and an adult format, a methodology that struck a chord with many readers for how honest they came across. Until it folded, that is, as ads began to dry up, contributing to its demise.

It wasn't hard to see why, and at the time, it seemed to be the biggest reason to me. PC Accelerator didn't name names, but I wagered that more than a few advertisers didn't like how opinionated they were about their clients. Ars Technica likened them to a "Monty Python troupe," which, as hilarious as they are, didn't have the kind of safe, universal appeal that certain other magazines at the time strove to maintain on family-friendly magazine racks elsewhere.

Fast forward to today, and it's as if the practices that helped fund those early publications with multi-spread ads back in the day is apparently still alive and well, reminding the survivors of who had helped to put them there.

To be clear, and as far as I know, this isn't indicative of everyone who writes about video games or whose business it is to cover this field. But at the same time, social media has accelerated the discussion with examples that have only served to pour gasoline on the very idea that the two have continued to be inseperable.

Even before the 'net exploded into what it is now, magazines such as the venerable and straight-laced CGW began running raunchy ads for XXX material in their back pages during the mid to late 1990s, something that brought its readership to write in and protest (the ads were eventually whittled down). Though ads like these have been running in other publications elsewhere, such as in the UK, they were surprising to see in CGW. It would have been if the Wall Street Journal set aside an entire section to tell you what the latest strip clubs were doing in New York city.

Today's controversy feels like it only underlines an age old problem, one that has only seems to grow even worse every time someone's bias is called out or when a journalist loses his job for simply being honest.

Even in print media, and with advertisement dollars being flaunted as an easy way to pad operating budgets, it's shocking to witness the results of this leverage in the last few years alone within the gaming space. There, it seems to be much worse thanks to its long and vivid association with the industry.

Perhaps more frustrating is in seeing at what journalism in gaming can promise from leafing through the older articles of those that have come before alongside the new journalists working at doing the same today. And then witnessing as another controversy explodes like an overripe Twinkie, complementing a dangerous narrative that buries the real work that is being done to fix it from articles like the ones here on Bitmob to books that take readers behind our favorite franchises.

Journalism in video games has always had a rich tradition that has penned its way through arcade stand ups, pinball machines, Saturn's early release, and venues beyond the ads and the PR interference they entail. It hasn't been an easy road and, like anything else in print, has had its ups and downs and has shown questionable integrity in the past. In that respect, it's in great company.

So in the end, for this scribbler at least, the only question left is that which is already being asked ever since Rab Florence had fired his warning shot across the bow of journalists everywhere: What can we learn from those events to not only stand back up but uphold the tradition that we've inherited to make it better?